Picture a volcano, like the one you learned about in primary school. Can you see it? Is it a big rocky mountain, perhaps with a bubbling pool of lava at the top? Is it perched above a chasm of subterranean molten rock?

I bet you didn’t picture this:

Rootless cones in the Lanbrotshólar district, S Iceland. Created by the 940AD Eldgjá eruption, there are over 4000 rootless cones in this area. Credit: Frances Boreham

You’d be forgiven for mistaking these small volcanoes for a scene from the Lord of the Rings, or maybe a grassy version of the surface of Mars (in fact, these kind of volcanoes do occur on Mars). These, however, are in Iceland and are called rootless cones.

These mini-volcanoes are unusual because they are ‘rootless’ meaning, unlike most volcanoes, they are not fed from the underground. To make them even stranger, they erupted only once and as part of the same event.

This type of volcanism is observed in several places around the world and occurs only in a unique set of circumstances. Despite showing similarities to more traditional volcanoes (like pyroclastic cones), the cones pictured above actually erupted several tens of kilometres from a ‘true’ volcano.

Rootless cones occur when a hot lava flow produced by an eruption travels away from the volcano and meets water. This can be a lake, a river, a glacier or simply a bit of soggy ground. The only criteria are that there needs to be water, and it needs to be trapped. Lava flows are usually at temperatures of over 1000oC and so, when they come into contact with trapped water or ice, its causes a build-up of steam, which can explode violently through the lava forming a rootless cone.

An article, published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research in September by volcanologists from the University of Bristol and the University of Iceland, analysed the shape and location of some of these cones to understand more about the environment in which they formed.

These features are found in northeast Iceland in the region around lake Mývatn. The area, 50 km east of the city of Akureyri, is world famous for its beautiful scenery and unusual landscapes.

The volcano responsible for the phenomena is the Þrengslaborgir–Lúdentsborgir crater row which erupted around 2000 years ago. The eruption produced a huge lava flow that covered an area of 220 km2; over 2% of the surface of Iceland. The flow, known as the Younger Laxá Lava, permanently changed the landscape, diverting rivers and damming lakes. After its extrusion from the volcano, the stream of molten rock meandered through different environments including river gorges and wide glacial valleys.

The flow’s diverse 67km journey allowed lead author Frances Boreham and her colleagues, to learn how it interacted with its surroundings. As she explains it, “one of the things that makes the Younger Laxá Lava such a great case study is the range of environments that the lava flowed through.”

Rootless cones do not all look the same and vary greatly in size, from small ‘hornitos’ which are about the size of a small car, to large crater-shaped cones hundreds of metres in size. The scale and complexity of the deposits makes them difficult to study as Boreham explains, “One of the biggest challenges is trying to understand and unpick the different effects of lava and water supply on rootless eruptions. We see a huge variety in rootless cone shapes and sizes, but working out which aspects are controlled by the lava flow and which by the environment and available water is tricky, especially when working on a lava flow that’s approximately 2000 years old!”

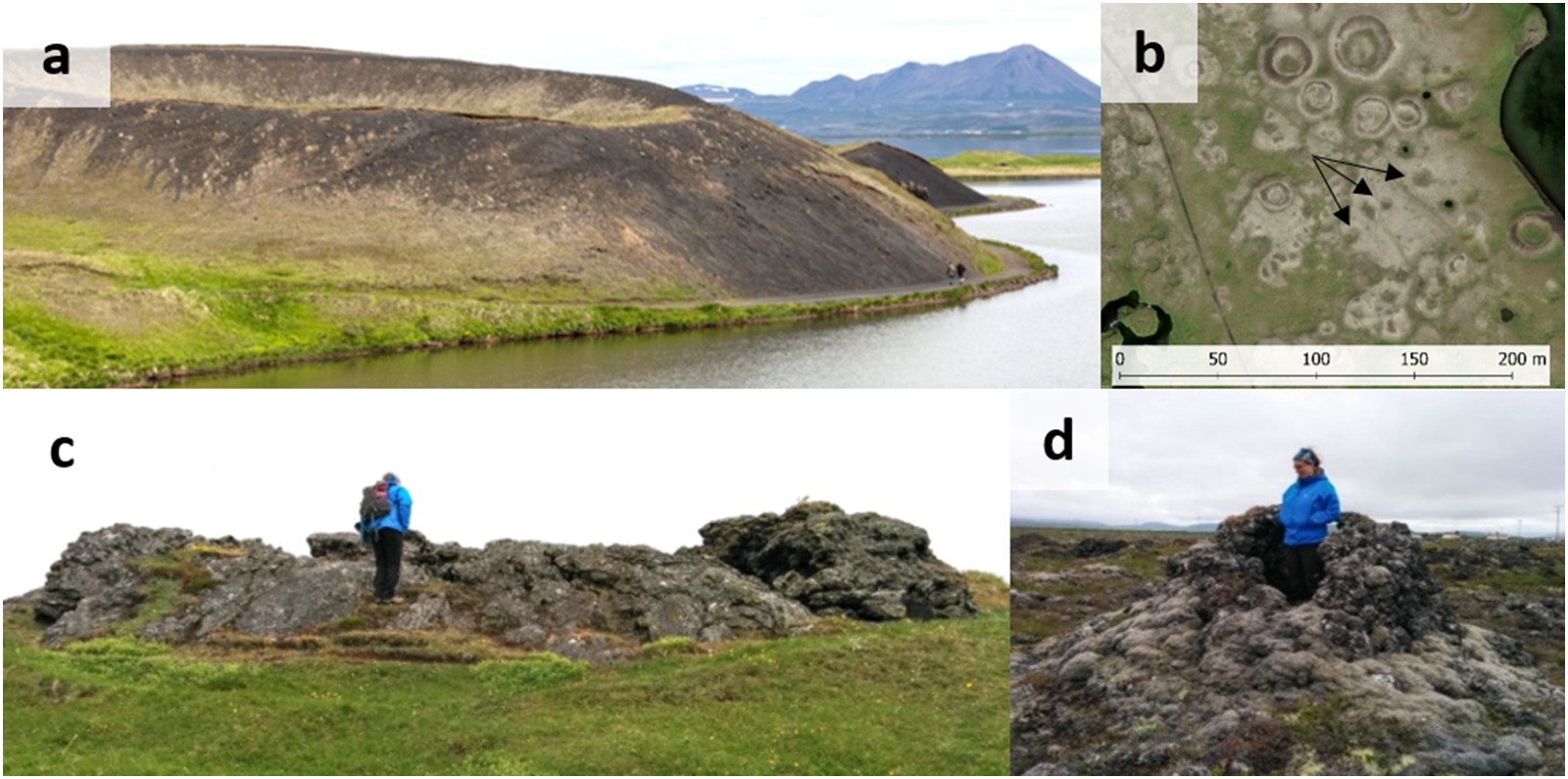

From Boreham et al. 2016. “Different types of rootless cone and associated features. a) Scoriaceous rootless cone at Skutustaðir, Mývatn. Cone base is ~100 m diameter. b) Explosion pits (marked with arrows) surrounding a scoriaceous rootless cone near Mývatn. c) Spatter cone at Mý d) Hornito in Aðaldalur, NE Iceland. Map imagery on d ©2017 DigitalGlobe, Google.” Licensed under creative commons.

Despite their beauty, the rootless cones represent a more serious issue. Lava flows are often thought of as quite benign compared to other volcanic hazards like pyroclastic flows. The presence of rootless cones suggests this isn’t always the case. “As far as I know, none of these rootless cones are currently taken into account for lava flow hazard assessments, in Iceland or elsewhere in the world. While not applicable everywhere, wet environments with a history of lava flows, such as Iceland or parts of the Cascades, could be affected and these hazards should be considered in future risk assessments and plans, e.g. by identifying vulnerable property, roads and infrastructure.” said Boreham.

By Keri McNamara, freelance science writer

Keri McNamara is a freelance writer with a PhD in Volcanology from the University of Bristol. She is on twitter @KeriAMcNamara and www.kerimcnamara.com.