Off the coast of Germany, a male northern gannet (for ease, we’ll call him Pete) soars above the cold waters of the North Sea. He’s on the hunt for a shoal of fish. Some 40km due south east, Pete’s mate and chick await, patiently, for him to return to the nest with a belly full of food.

Glints of silver just below the waves; the fish have arrived.

Pete readies himself.

Body rigid, wings tucked in close – but not so close that he can’t steer himself – he dives toward the water at a break-neck speed, hitting almost 100 km per hour. Just as he is about to hit the water, Pete folds his wings, tight, against his body. He pierces the water; straight as an arrow, fast as a bullet, and makes his catch.

The first of the day.

He’ll continue fishing for the next 8 to 10 hours.

As he does so, a tiny logger weighing no more than 48 g, will continually track Pete’s position and with every dive, the temperature of the sea water.

Why equip birds with sensors?

The physical properties of the oceans, such as water temperature, play an important role in determining where organisms are found in the vastness of the oceans. Life tends to concentrate in regions where there are temperature changes, be that as waters get deeper or across large horizontal distances.

Sea surface temperatures also reveal vital information about the global climate system, as they help scientists understand how the oceans are connected to the atmosphere. The data are used in weather forecasts and simulations of how the Earth’s atmosphere changes over time.

By mounting light-weight loggers on diving mammals (it needn’t be only birds, seals and penguins are good candidates too), scientists can learn a lot from the animal’s behaviour, while at the same time collecting data about the physical properties of the oceans.

That is why a German research team, led by Stefan Garthe of the Research & Technology Centre (FTZ) at Kiel University, has been tagging and monitoring the behaviour of a colony of northern gannets breeding on the German island of Heligoland. As a top marine predator, changes in the foraging behaviour of gannets can indicate changes in food resources, often linked to variations in the marine environment.

Flying northern gannets with a Bird Solar GPS logger attached to the tail feathers. Photo: K. Borkenhagen. From Garthe S., et al. 2017.

Their work is part of a larger project called The Coastal Observing System for Northern and Arctic Seas, or COSYNA for short, which aims to better understand the complex interdisciplinary processes of northern seas and the Arctic coasts in a changing environment.

The German Bight

The waters of the northern seas and Arctic coasts are governed by a large range of natural processes and variables, such as wind, sea surface temperature and tides. In addition, the North Sea in particular, is heavily used for human activities: from shipping, to tourism, through to exploitation (and exploration) of food resources, energy and raw materials – making it of huge economic value and importance.

But it is precisely this heavy human activity which is contributing to change and disruptions in the region. Scientists know that the biochemistry, food webs, ecosystems and species of the North Sea are being altered. However, the causes of the change aren’t well quantified or understood and their consequences poorly defined. This means mitigating and adapting to the changes is proving hard for scientists and policy-makers alike.

Where progress and nature collide

In an area so heavily influenced by anthropogenic activities, it’s not unlikely that observed changes to the properties of the waters of the North Sea and the German Bight (where Heligoland is located) are driven, to some extent, by human actions.

Since 2008, 12 offshore wind farms have become operational in the German Bight and a further five are under construction; 15 more have been given building consent too. However, what impact (if any) wind farms have on seabirds is a hotly debated topic. Their effect on the hydrodynamics, biogeochemistry and biology of the North Sea is also poorly understood.

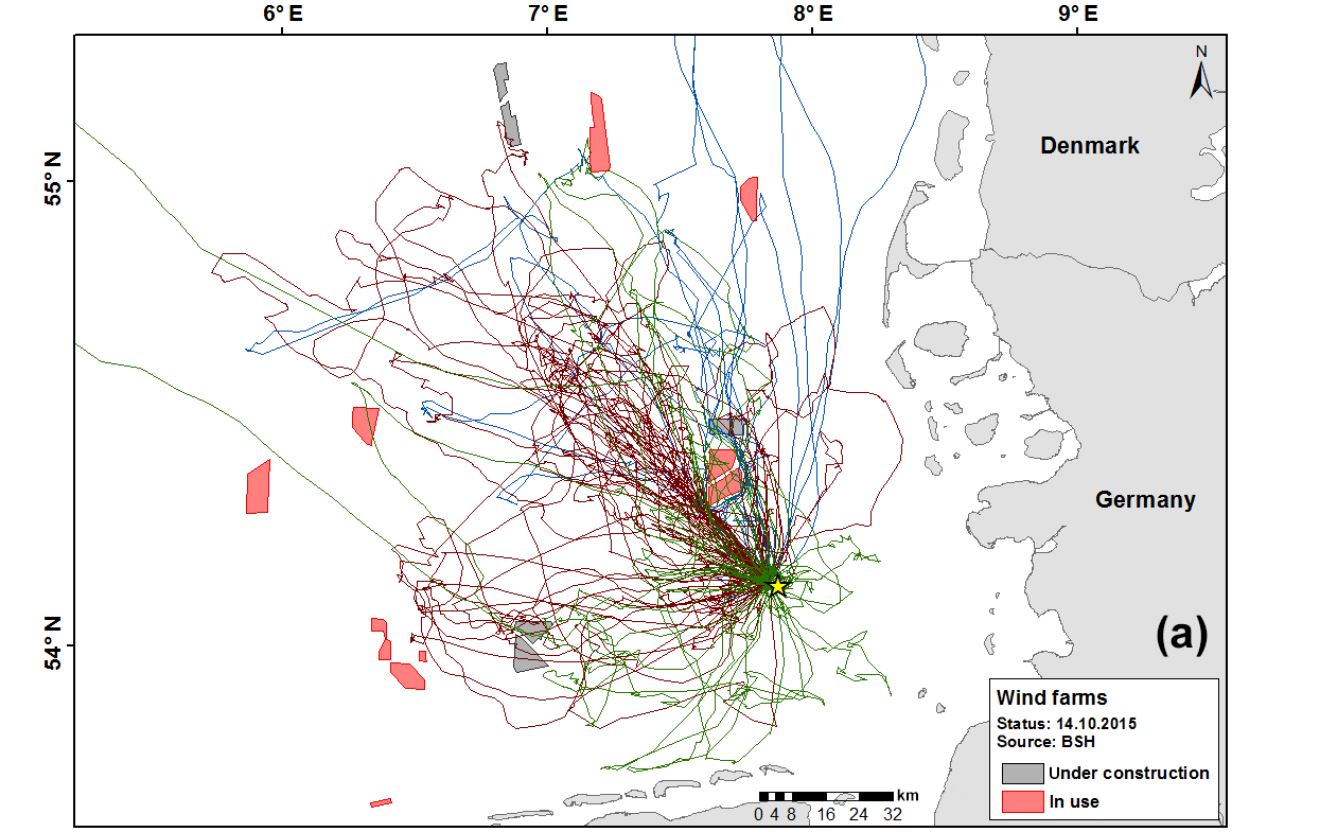

To unravel some of these questions, Garthe and his team tracked the movements of three individual gannets near existing wind farms in the North Sea. To find out their exact position, a GPS (mounted on the bird’s tail) was used and the flight tracks plotted on a map which also displayed the wind farms of the German Bight.

Overlap of flight patterns for the three northern gannets shown with the locations of wind farms in the German Bight. From Garthe S., et al. 2017.

Their results, published in the EGU’s open access journal Ocean Science, show that all three birds largely avoided the three wind farms just north of Heligoland. Though they visited sporadically, more often than not, the gannets flew around wind farms which also happened to be further away from their breeding grounds.

The team will now use the data acquired, which is of a much higher resolution than what has been available before, to understand how wind farms in the North Sea are affecting long-term seabird behaviour.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer.

References and further reading

Garthe, S., Peschko, V., Kubetzki, U., and Corman, A.-M.: Seabirds as samplers of the marine environment – a case study of northern gannets, Ocean Sci., 13, 337-347, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-13-337-2017, 2017.

Baschek, B., Schroeder, F., Brix, H., Riethmüller, R., Badewien, T. H., Breitbach, G., Brügge, B., Colijn, F., Doerffer, R., Eschenbach, C., Friedrich, J., Fischer, P., Garthe, S., Horstmann, J., Krasemann, H., Metfies, K., Merckelbach, L., Ohle, N., Petersen, W., Pröfrock, D., Röttgers, R., Schlüter, M., Schulz, J., Schulz-Stellenfleth, J., Stanev, E., Staneva, J., Winter, C., Wirtz, K., Wollschläger, J., Zielinski, O., and Ziemer, F.: The Coastal Observing System for Northern and Arctic Seas (COSYNA), Ocean Sci., 13, 379-410, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-13-379-2017, 2017.

Why do scientists measure sea surface temperature? (NOAA)

Scientists are putting seals to work to gather ocean current data (PRI)

Daunt, F., Peters, G., Scott, B., Grémillet, D., and Wanless, S.: Rapid-response recorders reveal interplay between marine physics and seabird behaviour, Mar. Ecol.-Prog. Ser., 255, 283–288, 2003.

Grémillet, D., Lewis, S., Drapeau, L., van der Lingen, C. D.,Huggett, J. A., Coetzee, J. C., Verheye, H. M., Daunt, F.,Wanless, S., and Ryan, P. G.: Spatial match–mismatch in the Benguela upwelling zone: should we expect chlorophyll and sea-surface temperature to predict marine predator distributions?, J. Appl. Ecol., 45, 610–621, 2008.

Wilson, R. P., Grémillet, D., Syder, J., Kierspel, M. A. M., Garthe, S., Weimerskirch, H., Schäfer-Neth, C., Scolaro, J. A., Bost, C.- A., Plötz, J., and Nel, D.: Remote-sensing systems and seabirds: their use, abuse and potential for measuring marine environmental variables, Mar. Ecol.-Prog. Ser., 228, 241–261, 2002.