This month’s GeoEd post is brought to you by Dr. Mirjam S. Glessmer. Mirjam, is a physical oceanographer and now works as Coordinator of Teaching Innovation at Hamburg University of Technology. Mirjam blogs about her “Adventures in Teaching and Oceanography” and tweets as @meermini. Get in touch if you are interested in talking about teaching and learning in the geosciences!

In my last post, I talked about hands-on outreach in very general terms, and identified four steps to great outreach. Today, I want to talk about those four steps in more detail, using one of my favourite outreach activities as an example.

Step 1. Identify the topic nearest and dearest to your heart

Me, I am a physical oceanographer. I care about motion in the ocean: Why and how it happens. Consequently, all of my outreach activities have to do with water. Sometimes at different temperatures, sometimes at different salinities, sometimes frozen, sometimes with wind, sometimes with ships, but always with water.

Today, let’s concentrate on thermohaline circulation as the topic we want to get people interested in. That sounds like a lot, so lets break it down: we want to know how oceanic circulation is influenced by both heat and salt in the ocean. To boil this down to one short activity, let’s take away the ocean (and with that all the complicating influences of Earth’s rotation, or topography of ocean basins) and only look at what heat and salt do with water in a tank. In fact, let us focus on different temperatures at first. The easiest way to do this is to introduce water of one temperature into a volume at a different temperature, this way we don’t have to deal with the heating or cooling processes.

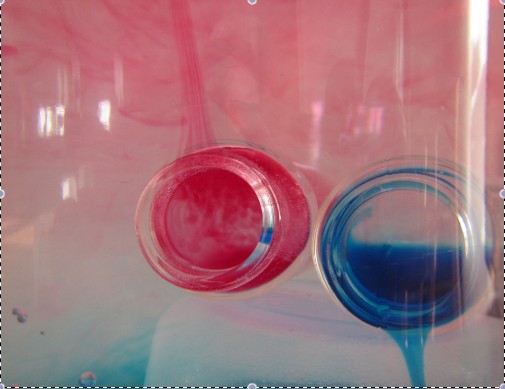

Introducing water can mean pouring it into the larger tank, which will lead to some kind of stratification (provided your temperatures are different enough). In order to see the stratification, it always helps to have food dye in the water you are introducing (always put food dye in the smaller volume of water, makes it a lot easier to see the contrast!). To make things most interesting, it might be nice to show two cases simultaneously: pouring hot water and cold water into a lukewarm tank. And, since we see that the hot water forms a layer on top of the lukewarm water and the cold water at the bottom, wouldn’t it be much more fun to introduce them both somewhere at medium height and see what happens?

Two bottles, one filled with hot water (dyed red) and one filled with cold water (dyed blue) in a larger container of lukewarm water. Credit: Mirjam Glessmer

Step 2. Find an intriguing question to ask

Depending on who you want to reach as your main audience, you might need to ask different questions. For some audiences, the focus needs to clearly be on your activity’s connection to climate. For other audiences, the questions can be a simple “Wow, that looks weird. Can you figure out what is going on here?”. Depending on the context I was doing my activity in, I could for example ask:

- Why is the bottle with the red water “pouring up”? The audience I might ask this question are for example kids in a school setting that I am wanting to get excited in science in general.

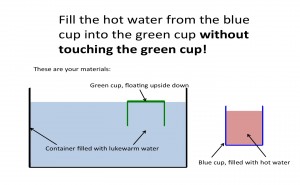

- How can I fill the green cup with hot water without touching it? Audience here could be the general public at a science fair, and if someone manages to fill the green cup, they win a sticker. This questions definitely makes people want to give it a try!

- What can these fingers tell us about how water mixes in the ocean? This question is for an audience that already knows a lot about the ocean and physical processes in it, for example university students, or a very interested general public.

- In the subtropical gyres you have a strong salinity stratification. How can nutrients get to the surface ocean? This question is closely related to the one before, but here the element of play isn’t as prominent. So this would be for an audience that knows a lot about ocean physics and biogeochemistry already, like university students or even colleagues at scientific conferences.

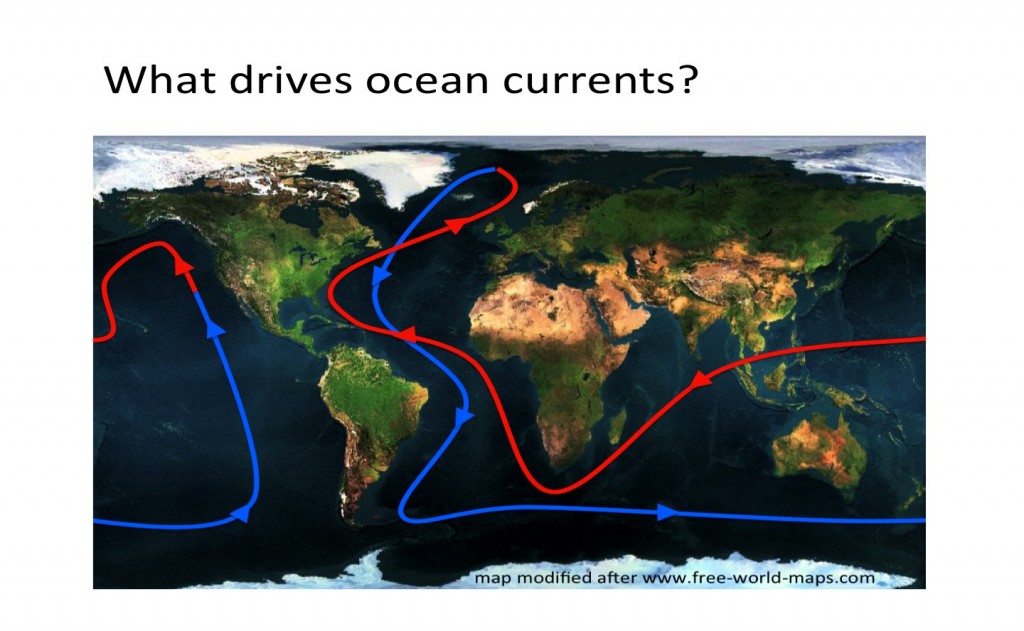

- What drives global ocean currents? This is again a question that you might ask the general public since on one hand not a lot of knowledge about ocean physics is required, and it is on the other hand very easy to see the connection between your activity and the ocean.

Step 3. Test with family, friends and colleagues

This step is important for several reasons.

First, you want to work out (most of) the kinks in the activity before using it in front of a large audience. This includes

- knowing what kind of materials you actually need to run it (For example, I tend to forget that I not only need large containers of water that are prepared at the right temperatures and salinities for several repeats of the experiment, but that in order to set up the experiment for repeats, I need somewhere to get rid of the water from previous experiments),

- seeing people get really excited about the activity (which is a good memory to calm you down when you get nervous about doing the activity in public for the first time), or, if the aren’t, a good time to tweak the activity a little.

Step 4. Bring all the materials you need, and have fun!

And there you are – ready to do your outreach activity! For your big day, this is what I would recommend:

- It sounds lame, but you should have a good packing list that includes not only stuff that you need to run the activity, but also stuff that you need to store stuff in on your way home, when everything is wet and full of food dye.

Ensure your activity runs smoothly by having a good packing list that includes which includes all the materials you need to run the activity. Source: Pixabay.

- If you are about to play with a lot of food dye or other staining substances, consider not wearing your favourite pair of white jeans. Consider also whether your scarf will be constantly hanging in your water tank getting wet, and whether your hair might get caught somewhere.

- Bring a friend to do the activity with you. It’s more fun, and it really takes away a lot of stressors if there are two people there (Run out of water? No worries, one of you can run and fetch more water while the other talks to people who still want to know what is going on. Question you have no idea how to answer? She will know, or you can look it up together later. Need the loo? How great is it that you don’t have to pack all your stuff and take it with you? ;-))

- Have someone you know for sure is interested in your activity show up early on to look at it and talk to you about it. Nothing makes it easier for other people to approach and join you in your conversation and activity as someone who is already there and obviously excited. (You can also use your friend mentioned above to play this role until things get going)

- Bring “backup materials”. Even if your activity is only very vaguely related to your research, bring a current poster of your research (maybe not the A0 version, but A3 or A4) and anything you typically show when talk about your research (Maps? Figures? Instrumentation?). When you get talking to people, chances are you will get talking about how your activity is related to bigger research questions, and you will want to be able to talk about them.

- And bring a different kind of “backup materials”: Bring pictures and/or movies of your experiment to show what it should have looked like in case the freezer that was supposed to have turned your ice cube tray full of water into ice cubes over night turns out to be a cold room.

Don’t forget that picture of you delivering your activity! It’ll come in handy for grant proposals or for end-of-year reports. Source: Pexels

- Take pictures. This one is super important, and I always forget about it in the heat of the moment. You constantly need that picture of you and a bunch of kids looking at your activity for grant proposals or for end-of-year reports!

- Last but not least: Have fun and take this as a great opportunity to play! Discover features in your activity that you have never noticed before, and, together with your audience, “improvise with the unanticipated in ways that create new value” – I guarantee that it will happen!

Do you have stories of your outreach to share? Any experiments we should all know about? I’d love to hear from you, please leave a comment below!

By Mirjam S. Glessmer, Coordinator of Teaching Innovation at Hamburg University of Technology

Pingback: The importance of playing in outreach activities. |