This Mind your Head blog post is a follow-up from Maria Scheel’s talk during the latest short course around mental health at #vEGU21. Before guiding a wonderful mindfulness pop-up event, Maria talked about how she struggled with unrealistic expectations, feeling insufficient and alone as a PhD student during the last lockdown. She turned this around by radically redefining her motivation, goals and structure and meditating regularly, as she explained in this EGU CR blog post. Many people resonated and expressed the need for more mindful approaches in science. We therefore invited Maria Scheel to share her five tips on mindful productivity with us!

Mindfulness and productivity might seem like opposing concepts – after all getting things done is stress- not peaceful, right? So why is there is so much fuzz about the term “mindful productivity”? Scientific work is asking huge mental efforts, when critically reading, writing, interpreting, analysing results, or differentially discussing these. Still, restoring and catering for our mental capacity is often seen as emergency treatment rather than prevention of the most common mental health issues, such as burnout in academia. While generic productivity usually has a clear focus on getting as much high-quality output as possible, mindful productivity also includes the sustainable use of mental energy and awareness of personal tendencies.

Here I share five tips to help you manage your working time and energy better. Before reading though, please remember to be patient with learning new habits, e.g. by trying one exercise per week to see how it fits you.

Journaling can help to become aware of unconscious emotions and drivers. Photo by Jessica Lewis from Pexels.

1. Learn how to pause and rest

You might be surprised to see rest as first advice for productivity, but it is exactly one of the major issues that seems to be misunderstood in academia. More working hours do not always lead to more output. To understand, why resting is productive, consider your body: if you work out every day, the muscle fibres can’t recover and grow. You need rest days in the gym. Mental capacity needs this rest too in order to be creative and innovative, especially for demanding tasks, such as fact-checking your paper or interpreting your results.

Subconsciously, when we try to rest, we often procrastinate by passively scrolling social media or video content. While the brain stays busy digesting all the input, it actually does not find rest. There are several forms of real rest, pauses from thinking and doing, e.g. by taking a walk, a nap or getting creative, that is: without multitasking other activities in the meantime.

Similarly, getting enough sleep is absolute key to both a healthy body and mind. Besides regular sleep, also micro pauses such as socializing, regular breathing or stretching exercises are key to recharge at work.

Exercise No. 1: Breathwork. Try box breathing in a situation of stress and tension, or on a regular basis, e.g. before meals: inhale for 4 seconds, hold for 4 seconds, exhale for 4 seconds, hold for 4 seconds and repeat.

2. You can’t (and don’t need to) always achieve 100%

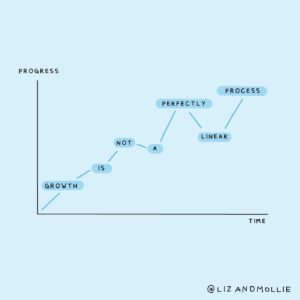

Growth is not a perfectly linear process. Source: Liz and Mollie via Twitter.

Now that we are rested and ready to lunge into work, let us remember the lessons from last year’s home-office: work outcome is not constant. Some weeks we might only face issues and lab work failures and on other days one week’s writing is done in a few hours. Your hormones create a daily, circadian rhythm and for many women also a monthly, infradian rhythm, which impacts your sleep, hunger and activity, and as such when you are communicative, focused or creative. You might have noticed that some colleagues come and leave early, while other need slow mornings and stay all night. Also, when we prefer to produce, e.g. write, or when we socialise is controlled by these hormone levels. These insights are stemming from metacognition – or observing how and when you work. A great resource to learn about how to use the day for the various tasks ahead is “Deep Work” by Cal Newport.

In a low productivity moment, it is easy to lose motivation, if you don’t feel like getting back on track. In this case, before knowing which next steps to take, you need to find your motivation. To do this, you might want to explore the “5 Why’s”. Why do you research this? But why (x4)? Just imagine your annoying but lovingly curious cousin and let them help you to get to the core of why you love your work.

Exercise No. 2: Reflection. If you do not already know, try to become aware if you are an early bird or late worker. What gets your workday going – a morning run or good breakfast? Which time of the day allows you best to focus fully? Then create no-disturbance blocks in these focus times (if you can) and put email, team meetings or other distractions in other hours of the day.

3. Beware of expectations

Frustration and guilt after failure often doesn’t stem from a lack of skills, but from too high expectations. We need expectations to plan and excel in our projects, but if they are not achievable, this can significantly impact your mental well-being. Feelings of insufficiency are common, even in higher academic positions.

One way to address this is looking carefully at the expectations of yourself and your PI or team you are trying to fulfil. Are they realistic and achievable for you? Becoming aware of this shines light into what often really motivates us to overworking and overachieving, resulting in burn out, stress or anxiety.

In science, naturally, results matter for progressing research and to keep personal research motivation up. But often academics tend to underestimate the value of the process to get there. As an example – while getting the academic title at the end of a PhD might matter in terms of career and personal success, the progress (3+ years of bravery, failure, curiousity and learning) matters equally.

Here, role models significantly help us lower the bar of expectation by showing their vulnerability. This serves as a reminder to not hide when you struggle and not judge when someone else does.

Exercise No. 3: Journaling. Whenever you feel a rush of guilt, start writing down which expectations you tried to fulfil. Are they realistic or even contradictory? E.g. do you expect from a normal workday to be working 8+ hours effectively, but also commute, do sport and meditate and keep up with relationships? Obviously unrealistic.

4. Know your goal and how to get there

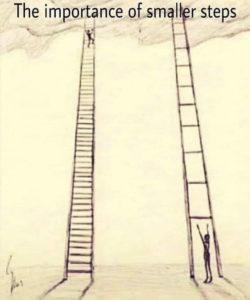

The magic of realistic steps. Source: Twitter.

Even in my second PhD year, I knew my motivation, valued rest, but still procrastinated. Why? I simply lacked an overview over my projects goals and that made achieving them feel impossible.

Since then I learned how to create structure from the big 5xWhy down to 3-4 milestones to achieve (3 year to yearly plans via Passion Planner), down to 3 month goal-setting (read more about the 12 week year technique), down to weekly tasks. From there on, every (work) morning, I am setting 3 tasks to focus on, no matter what else happens. And here the key obviously is to know which measures you need to take to achieve your goals. Publishing a manuscript might be a milestone, made up of various goals, like performing the analysis, writing the introduction, or reviewing. Each of these might be made up of smaller sub-goals, like reworking the last version, including former input, sending out to collaborators etc.

This might sound insignificant to you, but imagine two ladders – one of a few big and one with many small steps. Which one brings you up faster?

Exercise No. 4: S.M.A.R.T. goal-setting. You have probably heard of them, but did you ever apply them? Look at your planned task and analyse, if you really formulate them in a smart way. To make them as small and doable as possible will give you a better feedback on your work capacity.

SMART goal-setting is a key to achieving your goals through doable tasks. Credit: Maria Scheel.

5. Find (and maintain) your focus

Now that we set our internal motivation, goals and how to get there, we need the external setup. One skill immensely trained with mindfulness practices such as breathwork and meditation is: focus. This helps you to “eat the frog”, while life’s temptations are abundant.

To achieve focus, it helps to create a physical space that supports your mental work ahead: remove distractions and get your sticky notes close.

A second aspect is the misbelief that multi-tasking is possible. Neurologically, your brain will just be switching quickly between tasks, which is not energy-efficient. Try to put your head on one task at a time and write whatever arises on a notepad besides you – for later.

Finally, focus also comes from decluttering the number of projects you participate in. The art of saying no to extra projects is the art of helping your own research interest. And it is sometimes difficult to balance off curiosity and collaboration with the time and energy you have. But as a guideline: why do you say yes? Obligation? Because you actually have the time to help?

Exercise 5: Work environment. Do you need a clear space to focus or can you work in the lab in between incubations? Do you get inspired by social chatty offices or do you need a soundproof cave to focus? What distracts you most (food, smartphones?) and what helps you focus (silence, coffee)?

Find your aim, focus and go for it. Don’t just wildly throw darts. Photo by Engin Akyurt from Pexels.

EXTRA: Celebrate successes!

For the perfectionists, this might be hard to swallow, but you DO already progress a lot! Learn to see your successes, celebrate them and you will easily perceive yourself more realistically as that capable person you already are. That also counts for the people around you – we lift others up a lot by genuinely seeing them!

Most of these successes will actually show you some of your personal qualities and hopefully remind you, that, while striving for a career, life is out there wanting to be experienced by you fully.

Exercise: Successes. Write down all tasks you got done, all lessons learned, all successes of the day. Take it to the smallest details. Do this either after what felt like a bad day to see you still managed so much, or actually daily (I then keep it to min. 10, but really try to feel them).

Written by Maria Scheel

Edited by Elenora van Rijsingen

Credit: Maria Scheel.

About the author:

Maria Scheel is a third year PhD student at Aarhus University, Denmark, working with Arctic permafrost microorganisms, as such part of the EGU CR division. With her newly founded page Mindful Scientist she shares ideas, practices and perspectives on how mindfulness helps both scientists and science.