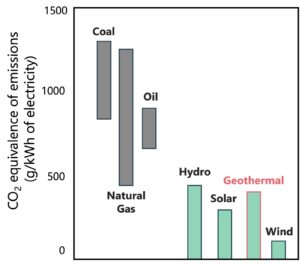

Imagine harnessing the Earth’s natural warmth to heat our homes and generate clean electricity. That is the promise of geothermal energy. It taps into the heat from beneath the Earth’s surface, providing a consistent and low-carbon power source. Geothermal energy plays a crucial role in reducing carbon emissions because it produces very little greenhouse gas over its entire lifecycle. Studies show that geothermal electricity emits approximately 38g CO2-eq per kWh, which is much lower than that of fossil fuels (IPCC, 2011). Because of this, geothermal energy is particularly important for achieving our climate goals, providing a reliable renewable energy source that complements wind and solar.

Greenhouse gas emissions by geothermal power plants. Reproduced from Rybach (2003).

Daunting task!

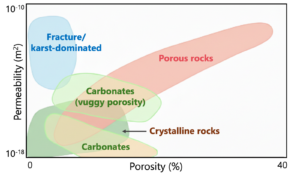

The development of geothermal energy is fundamentally an engineering challenge beneath the Earth’s surface. The initiation and successful implementation of any geothermal project do not commence with the selection of drilling equipment, but rather with a comprehensive understanding of the Earth’s deep architecture. While geochemists scrutinise fluid compositions and geophysicists visualise the subsurface, it is the structural geologist who provides the critical framework that elucidates the existence of resources, their flow paths, and sustainable access strategies. Their role extends beyond mere support, forming an essential foundation across all phases of exploration and development. Structural geologists are indispensable throughout the lifecycle of geothermal energy projects, primarily because the availability of subsurface heat seldom constitutes the limiting factor. Instead, the permeability of fluids within the crystalline basement predominantly determines the economic feasibility.

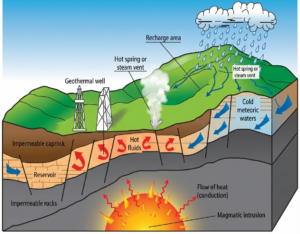

Schematic illustration of a geothermal energy system. Modified after fig. 1 of Syukri et al. (2018) using Gemini Nano Banana Pro.

Distribution of various rock types in the porosity v/s permeability field. Reproduced from Moeck (2014).

Where to look?

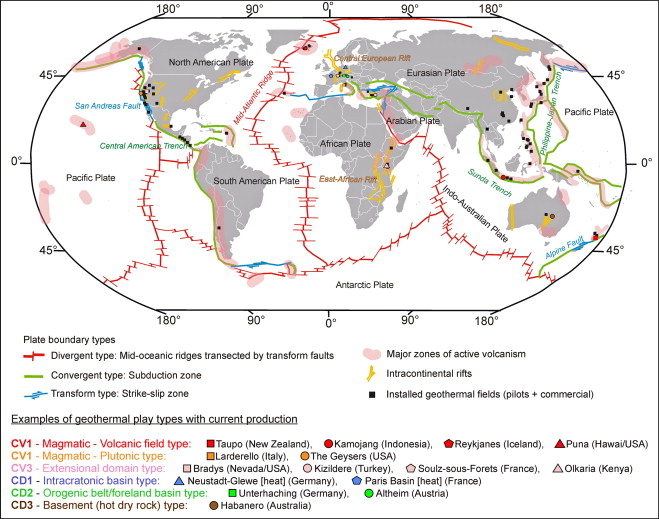

Understanding where to explore for geothermal energy is quite exciting! The first steps involve identifying promising regions, much like finding clues in a puzzle. Structural geologists are key players—they analyze the regional tectonic setting, which helps determine where the best chances are for discovering those hidden geothermal resources. The tectonic setting influences the nature of the heat source and the stress patterns in the Earth’s crust, which in turn affect permeability and, thus, the overall layout of the geothermal system (Alam, 2021; Santilano et al., 2015). Areas with extensional tectonics, such as continental rift zones, are widely recognised as hotspots for high-temperature geothermal activity (Rooney et al., 2025). The East African Rift System is a fantastic example, where crustal extension forms graben structures, normal faults, and fissures—allowing rainwater to seep deep into the Earth, get heated by the underlying mantle, and then surface as hot springs, fumaroles, and boiling pools (Jolie et al., 2019). Unlike many other countries, Japan benefits from its special location along the Pacific Ring of Fire – a convergent tectonic setting. The relentless collision of tectonic plates creates a furnace of active magma chambers and extensive hydrothermal systems, offering Japan a natural and reliable source of geothermal energy (Yasukawa, 2021).

Geothermal play types around the globe and their relation to the tectonic settings. CV – Convection dominated heat transfer, CD – conduction dominated heat transfer. Reproduced from Moeck (2014).

Highways for hot fluids

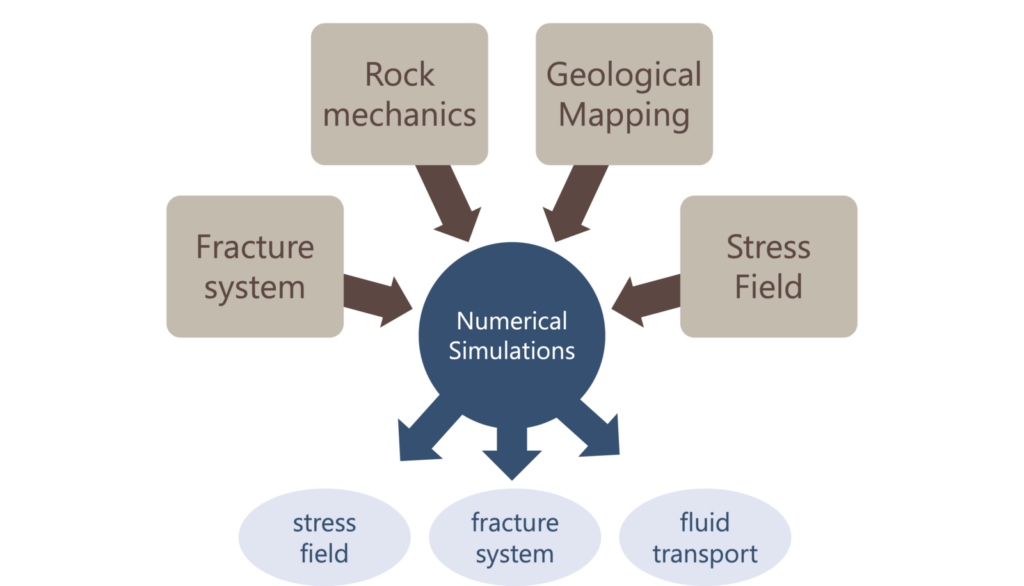

In conventional hydrothermal systems, natural permeability is primarily controlled by fault zones and fracture networks, which facilitate hydrothermal convection. That’s why, when exploring for geothermal energy, mapping these structures carefully is really essential. Once a promising geothermal area is found, structural geologists focus more closely on understanding the internal structure of the reservoir itself. This involves combining data from multiple sources, such as outcrops, boreholes, and seismic surveys, to develop a reliable model of heat and fluid flow (Caldeira et al., 2026). At a smaller, local scale, studying outcrops provides valuable real-world information about fracture features, including their orientation, density, size, and the minerals that fill them (Smith et al., 2022). These details, often captured digitally from scanned outcrops, help us run fluid-flow simulations and average the network to determine its overall permeability—an important factor in building accurate numerical models. Read more about digital mapping using drones here!

The structural geologist’s primary role during exploration is to identify these permeable pathways and develop detailed three-dimensional geological models. An important technical goal is to understand how existing fracture networks relate to the current in-situ stress field. Fractures that run parallel to the maximum horizontal stress tend to stay open or experience shear dilation when stimulated. Moeck (2014) identifies different geothermal play types, defined as “the heat source, the geological controls on the heat migration pathway, heat/fluid storage capacity and the potential for economic recovery of the heat”, noting that extensional regimes often exhibit higher permeability due to dilatant faulting.

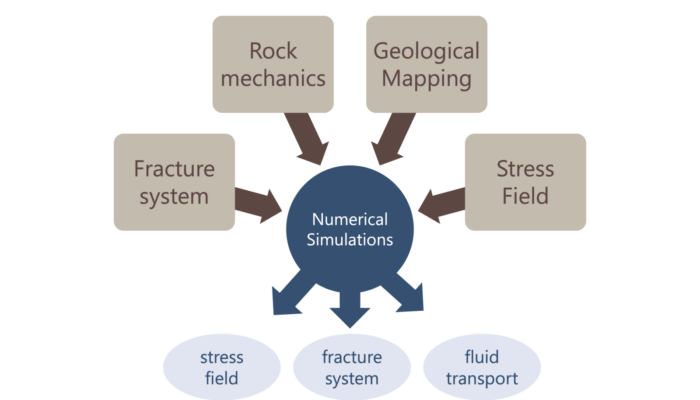

A structural geologist contributes by mapping the fractures, identifying the stress field, estimating rock strengths, and overall lithologic mapping. These can be used as inputs to numerical simulations predicting the evolution of a variety of subsurface characteristics over the course of the geothermal project. Modified after Philipp et al. (2007).

Enhanced Geothermal Systems

In some places, the rock is hot but not fractured enough. Here, engineers create “Enhanced Geothermal Systems” by injecting water to gently open existing cracks. Structural geologists help design these operations by predicting how fractures will respond. Using computer models of fracture networks helps ensure that water flows efficiently between injection and production wells without taking unwanted shortcuts (Sausse et al., 2010). This teamwork turns otherwise unusable rock into a viable energy source. Safety is another critical concern. When water is injected underground, it can sometimes trigger small earthquakes. Structural geologists help minimise this risk by studying nearby faults and assessing which ones might be sensitive to pressure changes. By analyzing the orientation of existing faults relative to the current stress field, structural geologists can identify which faults are critically stressed and could potentially be reactivated by changes in pore pressure. This knowledge informs safe injection strategies and helps mitigate environmental and safety risks. Ellsworth (2013) highlights that fault reactivation is governed by the proximity of faults to critical stress states. Structural geologists assess fault slip potential by integrating fault geometry, frictional properties, and stress data to establish traffic light systems for operational safety. Long-term reservoir management also relies on structural monitoring to detect subsidence or changes in fracture conductivity due to mineral precipitation or thermal stress. This careful monitoring protects both the project and the surrounding communities. Their knowledge of fluid pathways also aids in predicting how surface manifestations might change during development, which is essential for protecting fragile local ecosystems and communities. The viability of a geothermal resource is not determined by temperature alone, but by the structural framework that allows for sufficient fluid recharge, heating, and convective circulation. Structural geologists provide the essential expertise to unravel this framework, transforming broad tectonic maps into targeted exploration plans.

Beyond exploration – from science to policy

Structural geologists play a vital role as trusted advisors to environmental policymakers, helping to guide geothermal energy projects in a way that’s safe for communities and good for the planet. By translating complex underground data into clear risk assessments, they facilitate evidence-based decision-making. They act as a bridge between the fascinating science beneath the surface and the policies that protect our environment. Thanks to their expertise, policymakers can create regulations that safeguard ecosystems and communities while unlocking the promise of low-carbon, reliable energy. As governments increasingly turn to this knowledge, they are designing rules that are not only scientifically sound but also socially acceptable. For those working to develop a new energy sector, especially in challenging places like the Himalayas, the journey isn’t simple. These projects, while offering substantial long-term rewards, require significant upfront investments and involve uncertainties—such as whether a resource can be commercially viable (Kiran et al., 2024). Here, the work of structural geologists extends beyond science; it becomes a crucial component of risk management, development guidance, and policy formulation. Their insights help turn promising ideas into real, de-risked projects that can attract investments and earn public trust.

Further reading

Gutiérrez-Negrín, L. C. (2024). Evolution of worldwide geothermal power 2020–2023. Geothermal Energy, 12(1), 14.

Philipp, S. L., Gudmundsson, A., & Oelrich, A. R. (2007, May). How structural geology can contribute to make geothermal projects successful. In Proceedings European Geothermal Congress (pp. 1-10)