Our next Minds over Methods article is written by Derya Gürer, who just finished a PhD at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. During her PhD, she used a combination of many methods to reconstruct the evolution of the Anadolu plate, which got almost entirely lost during closure of the Neotethys in Anatolia. Here, she explains how the use of these multiple methods helped her to obtain a 3D understanding of the Anatolian double subduction system and the demise of the Anadolu plate.

Credit: Derya Gürer

Reconstructing oceans lost to subduction

Derya Gürer, Postdoctoral Researcher, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Subduction represents the single biggest recycling process on Earth and takes place at convergent plate boundaries. One plate subducts underneath another into the mantle, generating volcanism, earthquakes, tsunamis and associated hazards. Subduction zones come and go, and nearly half of the subduction zones active today formed in the Cenozoic (after ~65 Ma) (Gurnis et al., 2004). The negative buoyancy of subducted lithosphere (‘slab pull’) is thought to be the major driver of plate tectonics (Turcotte and Schubert, 2014). Changes in the configuration of subduction zones thus change the driving forces of plate tectonics, making the reconstruction of the kinematic evolution of subduction key to understanding past plate motions. Such reconstructions make use of data preserved in the modern oceans (marine magnetic anomalies and fracture zone patterns). But because subduction is a destructive process, the surface record of subduction-dominated systems is naturally incomplete, and more so backwards in time. Sometimes, relicts of subducted lithosphere are preserved in active margin mountain belts, holding valuable information to restore past plate motions and the dynamic evolution of subduction zones.

But how does one recognize a plate that has been almost entirely lost to subduction? And how do we reconstruct the evolution of subduction zones through space and time?

Archives of plates that were (almost) lost due to subduction

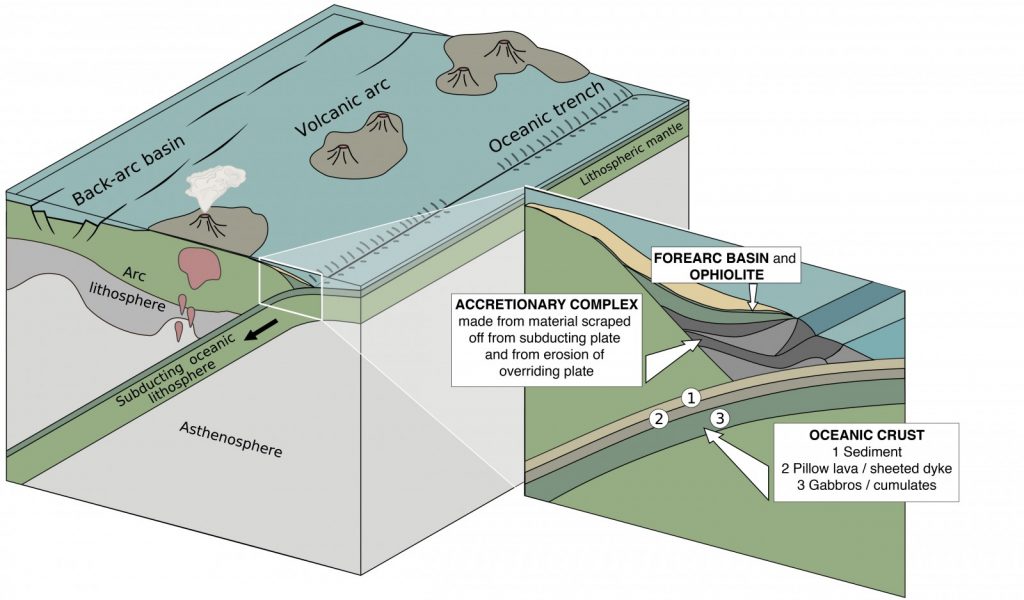

Subduction occurs in a variety of geometries and leaves behind a distinct geological record that holds key elements for the analysis of the past kinematics of now-subducted plates. Where subduction occurred below oceanic lithosphere, fragments of the leading edge of this overriding lithosphere may be left behind as remnants of oceanic crust (ophiolites). Subduction of oceanic plates may also be associated with accretion of its volcano-sedimentary cover to the overriding plate as an accretionary complex (Matsuda and Isozaki, 1991). Forearc basins associated with intra-oceanic subduction zones form on top of ophiolites and accretionary complexes and may record permanent deformation (syn-kinematic) of the overriding plate in response to tectonic interaction with the down-going plate (e.g., accretion, subduction erosion, slab roll-back) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: The location of archives of the evolution of “lost” oceanic plates (ophiolites, accretionary complexes, forearc basins) in a subduction zone setting.Credit: Derya Gürer.

The sedimentary infill of forearc basins implicitly records the nature and stress state of the overriding plate. Forearc basins may therefore hold the most complete record of the motion of the oceanic plate relative to the trench. However, many accretionary complexes and forearcs are deeply submerged and buried below sediments, making them highly inaccessible, and therefore expensive to study. As a consequence, our understanding of such systems is primarily based on well-studied examples in the East Pacific (e.g. Franciscan Complex, California (Wakabayashi, 2015)). Other such systems exist in the Mediterranean realm – for example in the geological record of Anatolia. The unique and direct archive of past plate motion in the geological record of Central and Eastern Anatolia is independent from constraints provided by marine magnetic anomalies, and provides a key region to unravel the evolution of destructive plate boundaries.

How many oceans were lost in Anatolia?

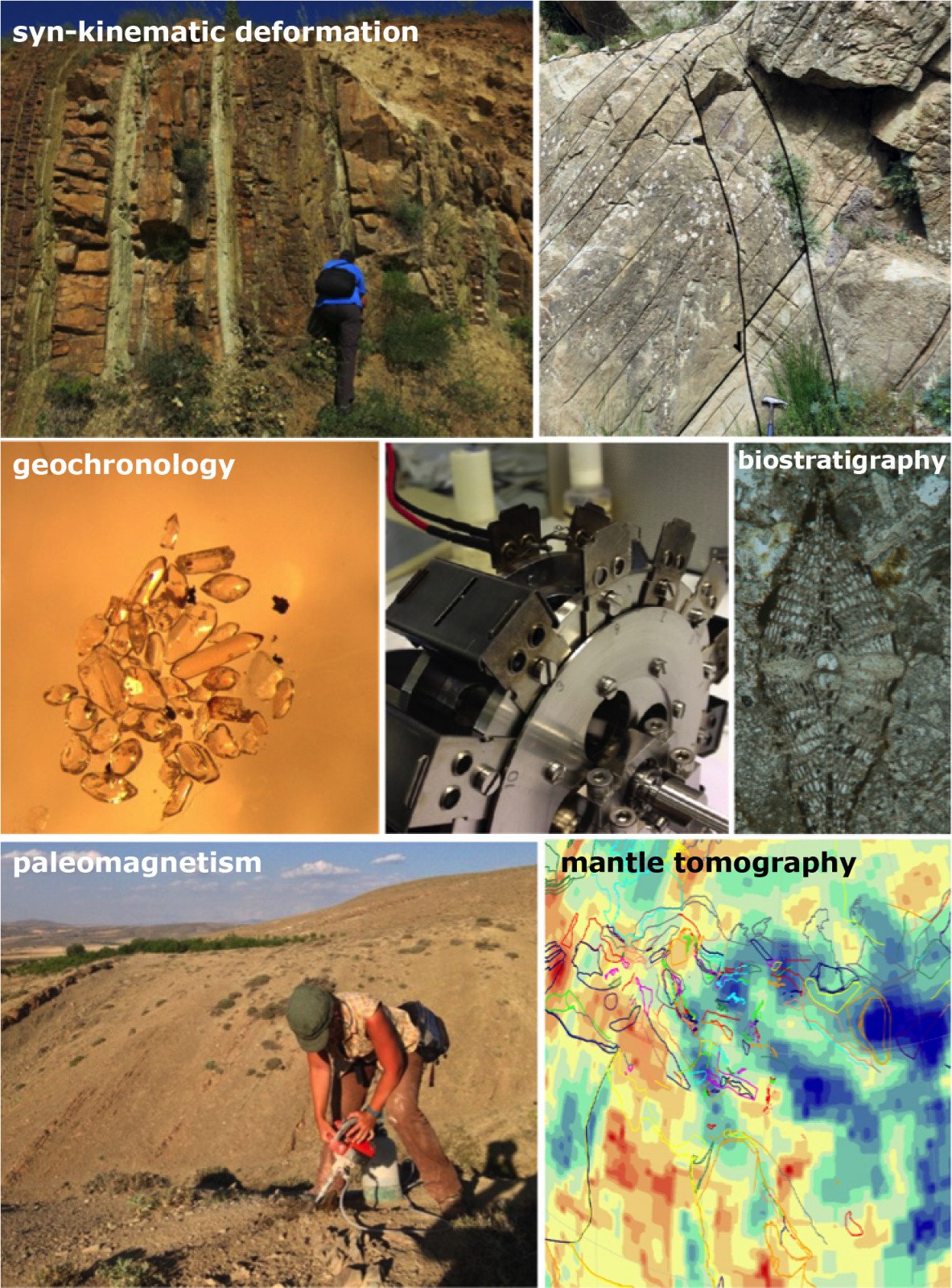

Fig. 2: The multidisciplinary approach used in my PhD research consisted of structural field analysis and stratigraphy of Anatolian sedimentary basins with focus on syn-kinematic deformation (top) with time constraints provided by absolute age dating of accessory minerals and biostratigraphy (middle). Paleomagnetic analysis (bottom left) provided information about vertical axis rotations. The combined information from these methods were integrated in a kinematic reconstruction and tested against mantle tomography (bottom right). Credit: Derya Gürer

To answer this question, I studied the deformation of sedimentary basins overlying Anatolian ophiolites (remnants of oceanic crust), and the deformation record of rocks which were buried and exhumed below these ophiolites. The Cenozoic deformation of the Anatolian orogen allowed for identifying the timing of arrest of the subduction history and revealed the simultaneous activity of two subduction zones in Late Cretaceous time. These two subduction zones bound a separate oceanic plate within the Neotethys Ocean – the Anadolu Plate (Fig. 3, Gürer et al., 2016). The aim of my PhD research was to reconstruct the birth, evolution and destruction of this oceanic plate.

Tectonic problems require a multidisciplinary approach, in order to study the evolution of orogens and associated sedimentary basins. My research involved the integration of (1) structural analysis, (2) stratigraphy, (3) geochronology, (4) paleomagnetism, (5) plate reconstruction, and (6) mantle tomography (Fig. 2). The main goal was to obtain new data on the evolution of the Central and Eastern Anatolian regions through the analysis of spatial and temporal relationships of deformation archived in the geological record.

First, I collected kinematic data from sedimentary basins (Fig. 2) overlying ophiolitic relicts of the oceanic Anadolu Plate, as well as from the underlying accretionary complex (Gürer et al., 2018a). Here, it was especially useful to focus on syn-kinematic deformation recorded by sediments. To constrain the timing of this deformation, I used geochronological data coming from absolute age dating and biostratigraphy. The integrated reconstruction of the kinematic history of basins was used to develop concepts quantitatively constraining the tectonic history of the Anadolu Plate and its surrounding trenches in 2D (Gürer et al., 2016).

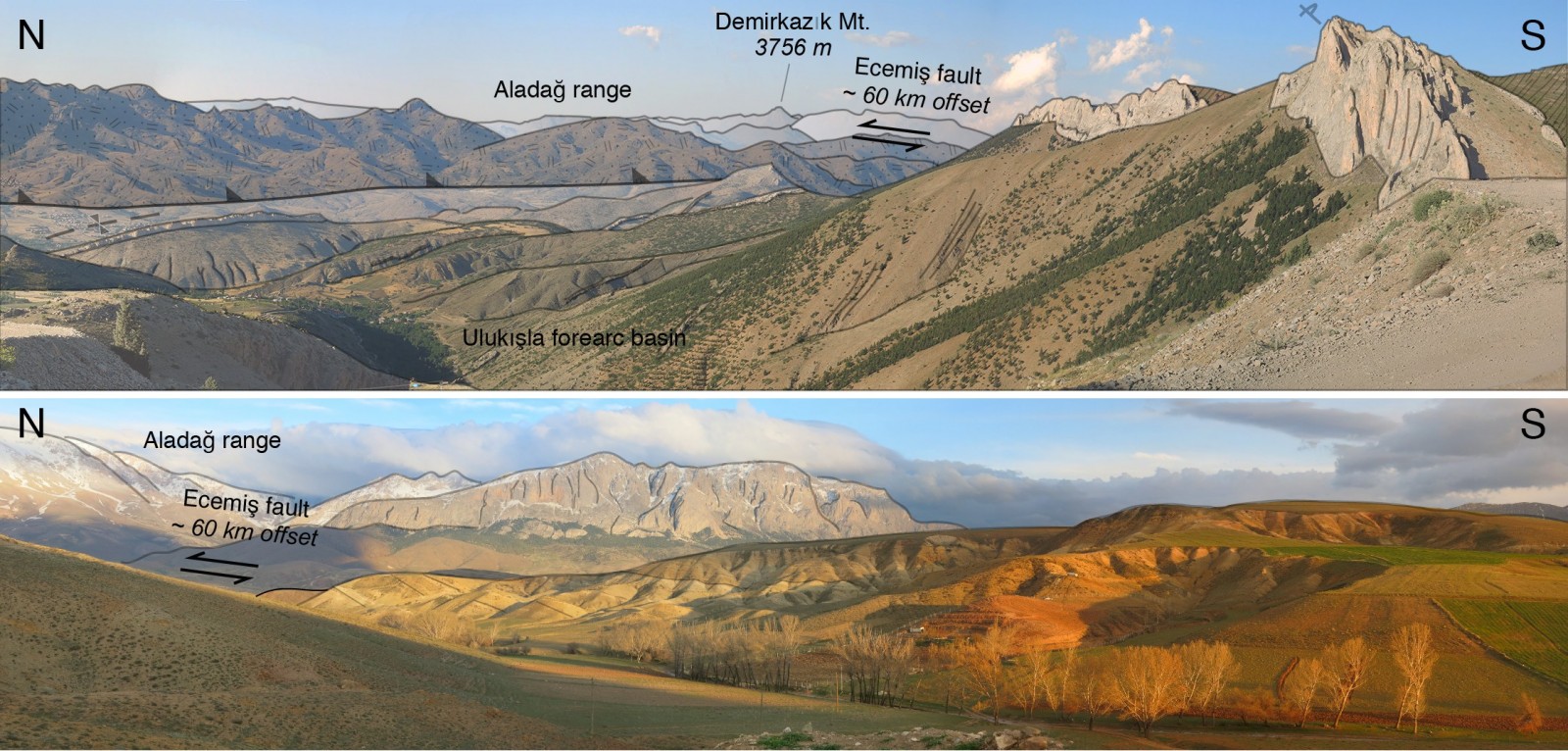

Fig. 3: The Ulukışla Basin (Central Anatolia) represents a forearc basin in Late Cretaceous to Eocene time which recorded the evolution of the Anadolu Plate. The basin has subsequently been strongly deformed during Eocene and younger collisional processes and is juxtaposed against the Aladağ range along the Ecemiş Fault. Credit: Derya Gürer.

There are, however, large vertical axis rotations constrained through paleomagnetic analysis within Anatolia, not taken into account in the workflow described in the previous paragraph. Therefore, paleomagnetic data from the Late Cretaceous to Miocene sedimentary basins were collected. These data identified coherently rotating domains and major tectonic structures that accommodated differential rotations between tectonic blocks (Gürer et al., 2018b).

Fig. 4: Simplified interpretation of the Late Cretaceous double subduction geometry in Anatolia and the Anadolu Plate.Credit: Derya Gürer.

Subsequently, a kinematic reconstruction of Anatolia back to the Late Cretaceous was built (Fig. 4) incorporating the timing of deformation obtained through structural analysis, stratigraphy, geochronology, and vertical axis rotations. This reconstruction provided first-order implications for the timing and geometry of subduction zones and revealed that the demise of the Anadolu Plate and collision in Anatolia was variable along the strike of the orogen, younging from the west to the east. The exact timing of collision in Eastern Anatolia will require future studies applying structural field geology, systematic analysis of the age and nature of magmatism, and thermochronology to constrain timing of regional exhumation, as well as detrital geochronology, providing information on the relative proximity of tectonic blocks through the provenance of sediments.

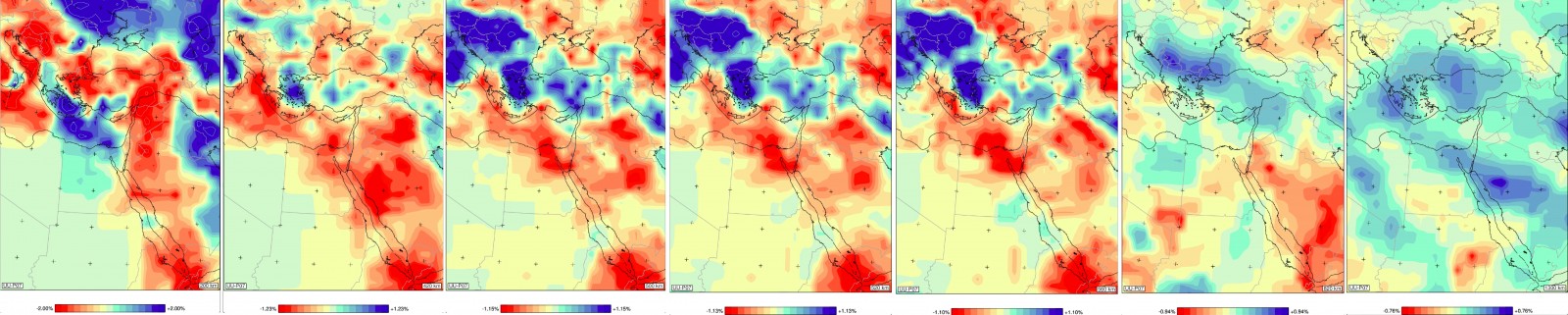

Finally, the resulting 2D kinematic reconstruction was tested against a mantle tomographic model (UU-07, Amaru, 2007; van der Meer et al., 2017) to gain insights into its 3D geometry. Mantle tomography images the present-day structure and positive seismic anomalies (blue colours in Fig. 5), which may be interpreted as subducted slabs. Comparing the convergence estimate obtained from the kinematic reconstruction with the imaged subducted lithosphere allowed to infer that the mantle structure in the Eastern Mediterranean holds record of not only the two strands of the Neotethys Ocean that existed in Anatolia, but also of the Paleotethys Ocean.

Fig. 5: Map view tomographic structure below the Eastern Mediterranean region at variable depths (increasing in depth from left to right). Blue colours generally represent positive, whereas red colours represent negative wave speed anomalies. Credit: Derya Gürer & Wim Spakman.

The combination of methods to unravel the geological record of Anatolia quantitatively constrained the evolution of subduction zones and of the Anadolu Plate. The reconstruction of the Anatolian double subduction system that existed in Late Cretaceous time has implications for the dynamics of multiple simultaneously active subduction zones.

References

Amaru, M.L., 2007. Global travel time tomography with 3-D reference models. PhD thesis, Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

Gürer, D., van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.D.J.J., Matenco, L., Corfu, F., Cascella, A., 2016. Kinematics of a former oceanic plate of the Neotethys revealed by deformation in the Ulukışla basin (Turkey). Tectonics 35, 2385–2416. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016TC004206

Gürer, D., Plunder, A., Kirst, F., Corfu, F., Schmid, S.M., van Hinsbergen, D.J.J., 2018a. A long-lived Late Cretaceous–early Eocene extensional province in Anatolia? Structural evidence from the Ivriz Detachment, southern central Turkey. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.10.008

Gürer, D., Hinsbergen, D.J.J. van, Özkaptan, M., Creton, I., Koymans, M.R., Cascella, A., Langereis, C.G., 2018b. Paleomagnetic constraints on the timing and distribution of Cenozoic rotations in Central and Eastern Anatolia. Solid Earth 9, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-9-1-2018

Gurnis, M., Hall, C., Lavier, L., 2004. Evolving force balance during incipient subduction. Geochemistry Geophys. Geosystems 5, Q07001. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GC000681

Matsuda, T., Isozaki, Y., 1991. Well-documented travel history of Mesozoic pelagic chert in Japan: from remote ocean to subduction zone. Tectonics 10, 475–499.

van der Meer, D.G., van Hinsbergen, D.J.J., Spakman, W., 2018. Atlas of the Underworld: slab remnants in the mantle, their sinking history, and a new outlook on lower mantle viscosity. Tectonophysics 723, 309–448.

Wakabayashi, J., 2015. Anatomy of a subduction complex: architecture of the Franciscan Complex, California, at multiple length and time scales. Int. Geol. Rev. 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2014.998728

Tarhib IT Limited

What a fascinating read! The author’s insights into reconstructing lost oceans through subduction are truly impressive. Thanks for sharing this gem!