As an EGU division blog, we facilitate that the most recent cryoscientific insights reach a wider audience. To do this, we have a team of experienced editors (and former authors), but we also love helping first time authors getting experience with outreach. But if you have ever written an outreach piece, you might know that it can be more difficult than expected to write down your research in simple words. You might have heard before, that discussion that half of all academic papers not getting cited. Get ready to learn what that has to do with your grandmother and science communication. With this blog post, we want to summarise some of our top tips to connect your research to (y)our readership.

The peer bubble and why to pop it

As scientists, we had many years of professional training, and are used to having our scientific jargon heard in the specialist, or “peer bubble”. Additionally, in most graduate studies, a class or workshop on how to write and publish papers will be offered. However, a guide how to write for wider, non-academic audiences often is not (nor why you would do that). Rather, science communication is seen as unnecessary distraction to most PhD supervisors.

This is (still) a gap in the academia. Not only does clear communication help in any relationship (personal opinion of the author), but also when writing funding calls (often the committee is outside your expertise) and even when presenting at an interdisciplinary conference or journal issue. Often, you will need to introduce your research to a diverse and non-specialist audience. (Science) Communication is a crucial skill to learn, to allow also the general public to appreciate, understand and participate in the work we do. In a time of misinformation and short attention spans, getting to the point is important. Yet it seems even more daunting to a general audience than to your science mates (often lovingly dubbed as “Imagine you are explaining what you do to your grandma or best friend”).

Fig. 2. When communicating our thoughts, we often just write them out. But equally important is thinking about the recipient. Can they understand my message clearly? What do I want them to communicate back to me? [Credit: Image by Sasin Tipchai from Pixabay]

How to make your research approachable in six thoughts

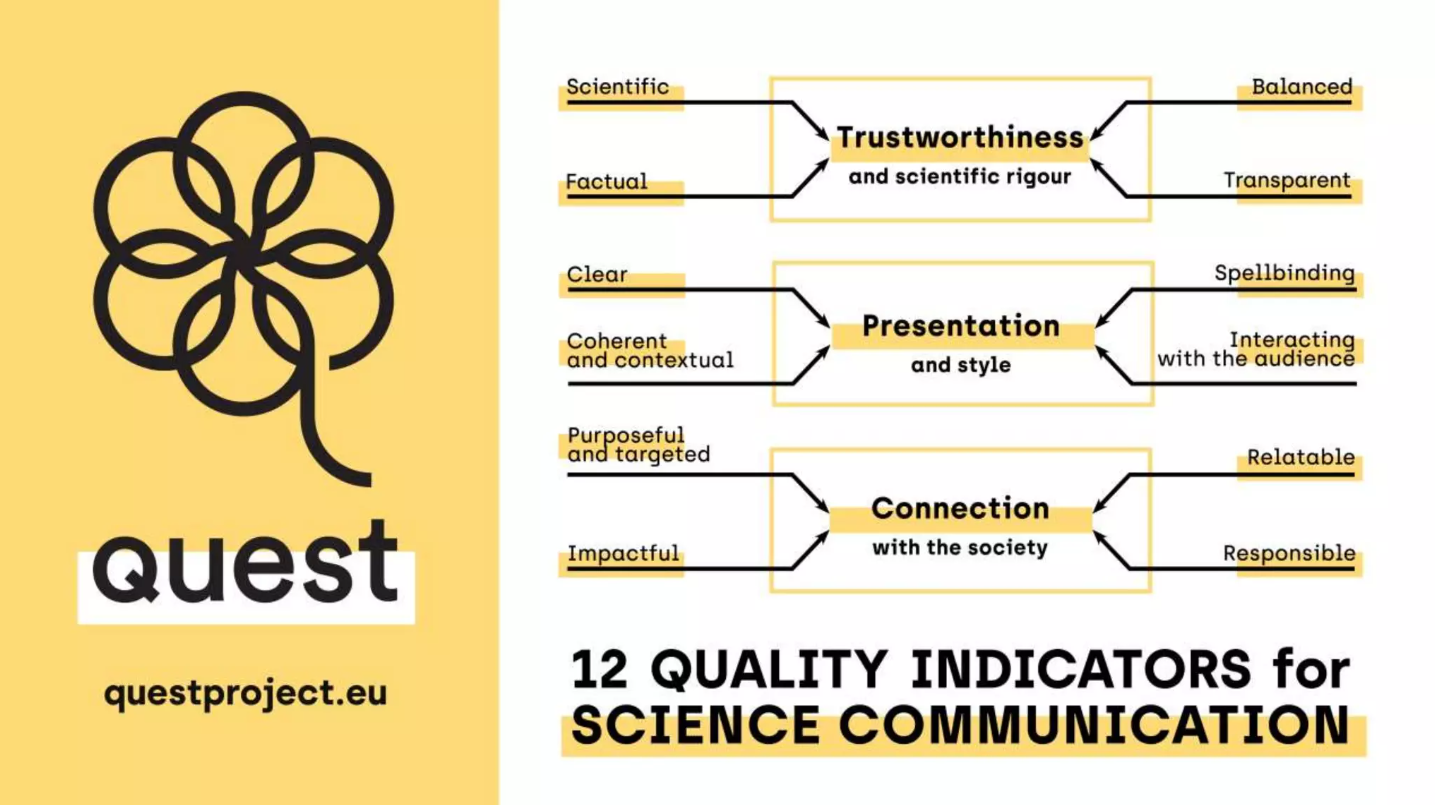

“Communicating clearly” might sound vague, so here are a few guiding thoughts on how to achieve it. You might think about a specific upcoming communication moment – a conference presentation, a funding or paper summary, meeting your friend and explaining them a new project. To learn a bit what could also make a good blog post (😉), as a general order of things, these six thoughts might guide your process. Many of these points were described in the Quest Project with 12 aspects of “good” scientific communication (Fig. 3)

1) Think about what your key message is, in one simple sentence (this will likely become your title, but feel free to add some poetic spice or humour to it).

2) Who is the audience you want to write for (and why)? Other scientists in or outside your field? Funding agencies? Friends and family? What do they (not) know? This defines, which areas you will need to provide with more context.

3) One aspect that is often left out in science communication is the question, what do you want as a reaction from the reader? Do you want them to contact you? Employ or fund you? To reflect and change habits? To spread your message? We live in a time where content is ever abundant. So making your post entertaining and adding a clear “Aha!” moment, will make it an experience that engages the reader to want to know more.

4) Being relatable and digestible. That means, a text will have an easy flow, also to an audience of largely non-native speakers of English. This can be achieved with humor, shorter sentences, but also links or explainers to specific terms. Science jargon can create the feeling in the reader, of “not knowing enough”. In 2 minutes reading time, a reader also won’t look up every unknown term and rather close the item your wrote – that is except if you just introduce them well! Also addressing the speaker directly “You might wonder, what …”, is an engaging and light way to stay in connection with, rather than lecturing a reader (Fig. 2).

5) Don’t change, what you write about, but how! The art is writing simply, but not dumbing/cutting information down. If your project has three methods, keep your scientific integrity to explain them, rather than skipping, what seems “too complicated”.

6) The visual presentation. Now imagine you were a reader and you only had 2 minutes (the average time a reader spends on a blog post): how can you pack your information in small enticing packages? This is why we use subheadings, images, quotes and spaces every 5 or so (short!) sentences.

Fig.3 The Quest project found 12 of them and grouped them related to scientific rigour, presentation and societal connection. (Image credit: QUEST Project).

(Permafrost) Examples of great outreach

While there are many amazing blog posts, visual experiences and more about scientific outreach, these two scientists and their science became memorable, also because of they we they reached into the general public. You might know many scientists turned great communicators, such as Neil deGrasse Tyson, Jane Goodall or Antje Boetius, that through their work almost caused societal shifts of how (their) science is perceived.

However, I want to showcase a few (permafrost) scientists, that in my eyes are creative but also very efficient in getting their science (and passion) out there.

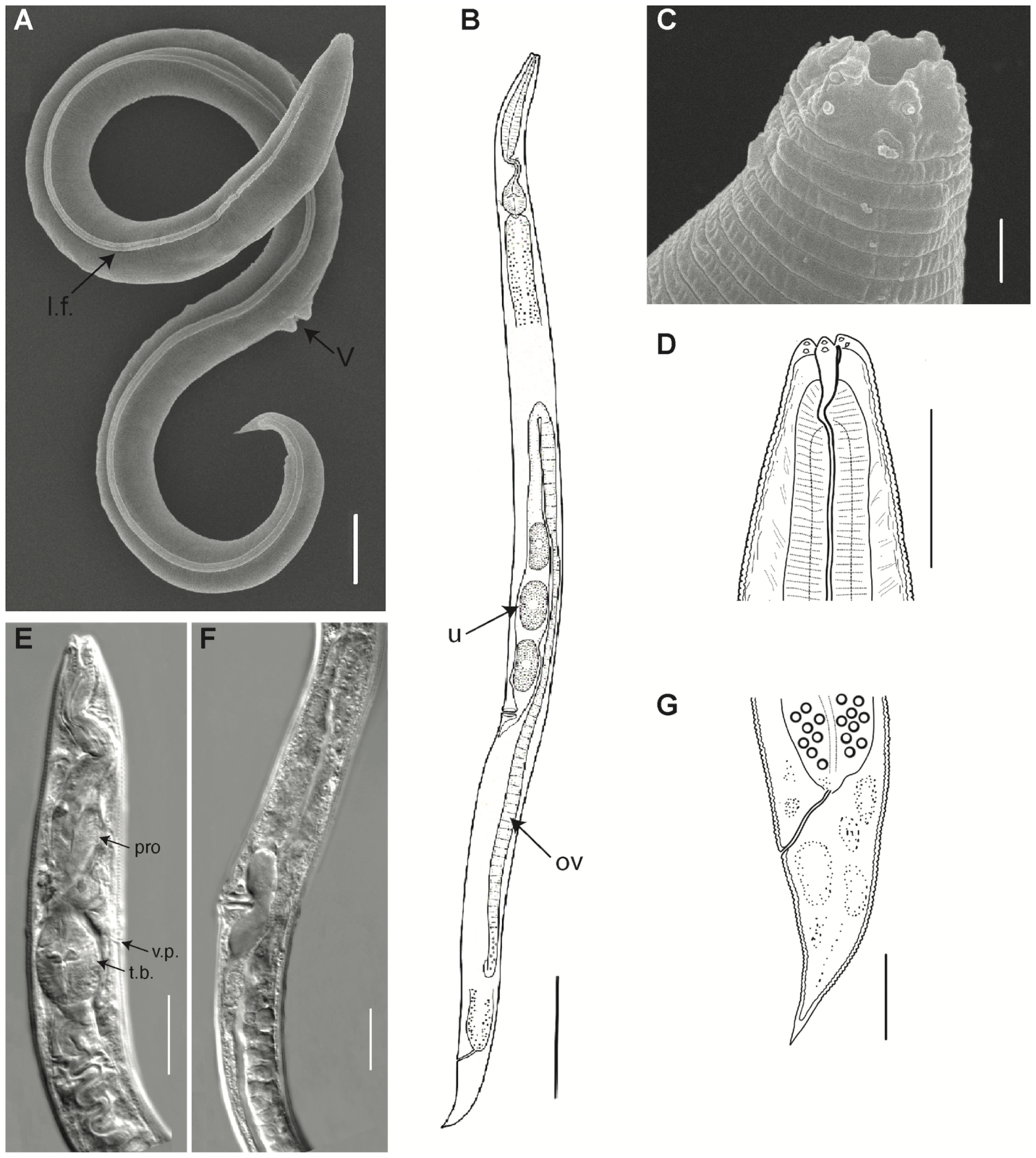

1. Anastasia Shatilovich, colleagues and the ancient permafrost nematodes

You might remember the EGU CR permafrost worms blogpost about this publication. While (especially permafrost) microbiology often only matters to the general reader, when it affects human health, a twitter outrage about living tiny worms in permafrost by Shatilovich et al. 2023 made it to literally every North American news outlet went for the story went viral, from NPR to CNN and also the Scientific American. Youtube videos, blog posts, you name it. The reason might be because the authors reached out to media platforms actively, but likely (I did not ask them), the success of their story might be due to: readers being able to relate to the topic. For that, something very helpful is the microscopic photo they supplied of the worm, which was used on every platform I have seen (Fig. 4). And in comparison to carbon fluxes, changing temperatures and ecological cascades, a worm in frozen soil is something we can imagine and see.

Fig. 4 Lightmicroscopic images and sketches of nematodes found in permafrost by Shatilovich et al. 2023.

2. Creating educational and passionate content: Rachel Mackelprang

Well, speaking of anthrax – permafrost scientists get contacted too often about “pests” and their risk for our civilization, rather than for the seemingly more important warming caused by permafrost carbon release. Naturally, we need to feel connected to a topic in order to want to understand it. Another great communicator in permafrost is Rachel Mackelprang, who uses this principle and created some amazing tweet-threads, declaring her love for peats (hence the infamous “peatqueen”), while playfully explaining the quirks and beauty of that vast ecosystem). Using simple (and plentiful!) graphics, she often makes slides available for everyone.

Find one of the slide shows she made available about Anthrax in permafrost – another topic all too popular in general media, and sadly often also a source of misinformation.

Hopefully, this post left you feeling inspired, surprised or motivated to see communication as the great chance of connecting that it is, rather than a burden to carry in addition to your academic research. And if your supervisor ( or inner critic) might need an argument, plenty studies like this one found increased publication metrics for happily chatting scientists 😉

Further reading

– Incredibly fact-based and yet great to read blog post about the struggle to relate to scientific texts and how to fix that! Highly recommend!

– A great place to get inspired by keeping scientific integrity while softening to the audience in my eyes are the Frontiers kids articles written for and edited by juniors. If you really want to check how well you know your science to the core, try explaining it to kids (seriously, it is a great journal to even publish in, check it out)!

Edited by Emma Pearce

Maria Scheel is a Postdoc at Aarhus University in Denmark, working in the Netherlands. Her PhD research explored how permafrost microorganisms adapt to the ongoing thaw and erosion in Northeast Greenland permafrost. She uses genetic tools to discover how Arctic life responds to climate change related stressors. She is also author and one of the EGU CR blog chief editors and happy to get back at you via maria.scheel@envs.au.dk.

Maria Scheel is a Postdoc at Aarhus University in Denmark, working in the Netherlands. Her PhD research explored how permafrost microorganisms adapt to the ongoing thaw and erosion in Northeast Greenland permafrost. She uses genetic tools to discover how Arctic life responds to climate change related stressors. She is also author and one of the EGU CR blog chief editors and happy to get back at you via maria.scheel@envs.au.dk.