Sea level rise

Sea-level rise is one of the main impacts of the current global warming and its rate has dramatically increased in the last decades (the current rate is about 3 mm per year). Even if greenhouse gas emissions were stopped today, sea level would continue to rise due to the slow Earth climate system response (IPCC, 2013, chap. 13). It is therefore a considerable threat for populations living close to the coastlines with the big cities most at risk.

Storing water in Antarctica

Modelling water storage

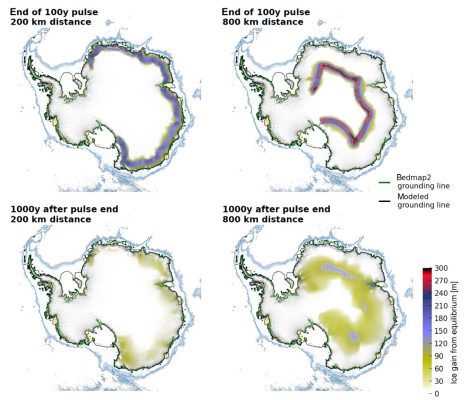

In order to face sea-level rise, many adaptations measures have been planned and already taken (e.g. building barriers and dikes, broadening dunes). In a recent study, Frieler et al. (2016) investigated the possible pumping of sea water from the Southern Ocean and its storage as ice in Antarctica in order to delay sea-level rise. Once on top of the ice sheet, this water would freeze to solid ice. The authors used the Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM) to estimate the ice sheet response’s to different ice addition scenarios starting from an equilibrium state. In the experiments, ice was continuously added for 100 years, then this addition was stopped and the model was run for 1000 years to quantify the subsequent ice loss through discharge to the ocean.

What would happen?

One of the key results is that the distance from the coast at which the water is added to the ice sheet strongly controls the ice loss 1000 years after the forcing ends. When the ice is added 200 km from the coastline, 10 to 15% of the added ice is already lost after 100 years and most of it is lost 1000 years after the end of the forcing, contributing to sea-level rise. When the distance is 800 km from the coastline, the ice-sheet contribution to sea-level rise is strongly delayed and a broad ice gain persists after 1000 years (see figure).

Practical considerations

Even if pumping water onto Antarctica could delay future sea-level rise, this solution would need to overcome technical difficulties. For example, the energy needed to pump water onto the surface of the Antarctic ice sheet would be about 7% of the current global primary energy supply! In order not to enhance further the current global warming, this energy would need to be generated from renewable sources, e.g. from wind farms installed on the Antarctic continent.

Food for thoughts…

This original study finally raises the question: do we value the uninhabited Antarctica more than we value our populated coastlines? It does not provide an answer but gives some insights. The impact of such a solution on the environment and the global economy would need to be further investigated. Even if this adaptation measure would delay sea-level rise, future generations would pay the price when the ice addition is stopped. Therefore, carbon emission mitigation measures are currently the safest way of not deteriorating our environment.

Reference

Frieler K., Mengel M., Levermann A. (2016). Delaying future sea-level rise by storing water in Antarctica, Earth System Dynamics, 7, 203-210, doi: 10.5194/esd-7-203-2016.

(Edited by Sophie Berger and Emma Smith)

David Docquier is a post-doctoral researcher at the Earth and Life Institute of Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) in Belgium. He works on the development of processed-based sea-ice metrics in order to improve the evaluation of global climate models (GCMs). His study is embedded within the EU Horizon 2020 PRIMAVERA project, which aims at developing a new generation of high-resolution GCMs to better represent the climate.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Delaying the flood with glacial geoengineering