Cryosphere scientists know it well; the Arctic doesn’t give up its secrets easily. This is especially true when it comes to exploring permafrost -– frozen soils that store centuries of history underground. Keeping an eye on the state of permafrost is more important than ever, as widespread permafrost thaw is a direct result of rising global temperatures. However, monitoring the vast Arctic is not exactly a task you can handle with just a pair of binoculars and a notepad.

This is where UndercoverEisAgenten enters the scene: a citizen science project with a name fit for a spy-movie and the objective to bring everyday people into real-world science. In a recent study within the UndercoverEisAgenten project, researchers asked themselves: can citizen scientists map permafrost features as reliably as academic experts? Spoiler: yes, they can!

Monitoring Permafrost is a hot topic

The Arctic is warming up significantly faster than the rest of the Earth. This temperature change leads to the thawing of permafrost. When the permafrost thaws, greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide and methane) are released, which—you guessed it—further accelerates global warming. Subsurface thaw also causes the ground to sink, with devastating effects on buildings and roads.

Mapping permafrost landscapes, and monitoring how they change, is increasingly relevant for climate-related research and action.

Why did we turn to Crowdsourcing?

Given the large scale of permafrost landscapes in the Northern Hemisphere, automated methods may sound like the obvious solution for mapping permafrost patterns. However, many automated approaches rely on high-resolution elevation models that show the shape of the land surface in fine detail, and those aren’t easily available in the Arctic.

So, the research team had to turn to the power of the human mind. Even when machines struggle, humans are pretty good at spotting the characteristic patterns of ice-wedge polygons by eye in aerial images.

But there’s another catch: The complicated patterns make it much too complex to ask volunteers to draw the full outlines of these polygons, even at a scale of thousands of volunteers.

So the research question became: What if volunteers didn’t have to outline the polygons at all? What if they just marked the approximate center point and let a spatial processing pipeline take over from there?

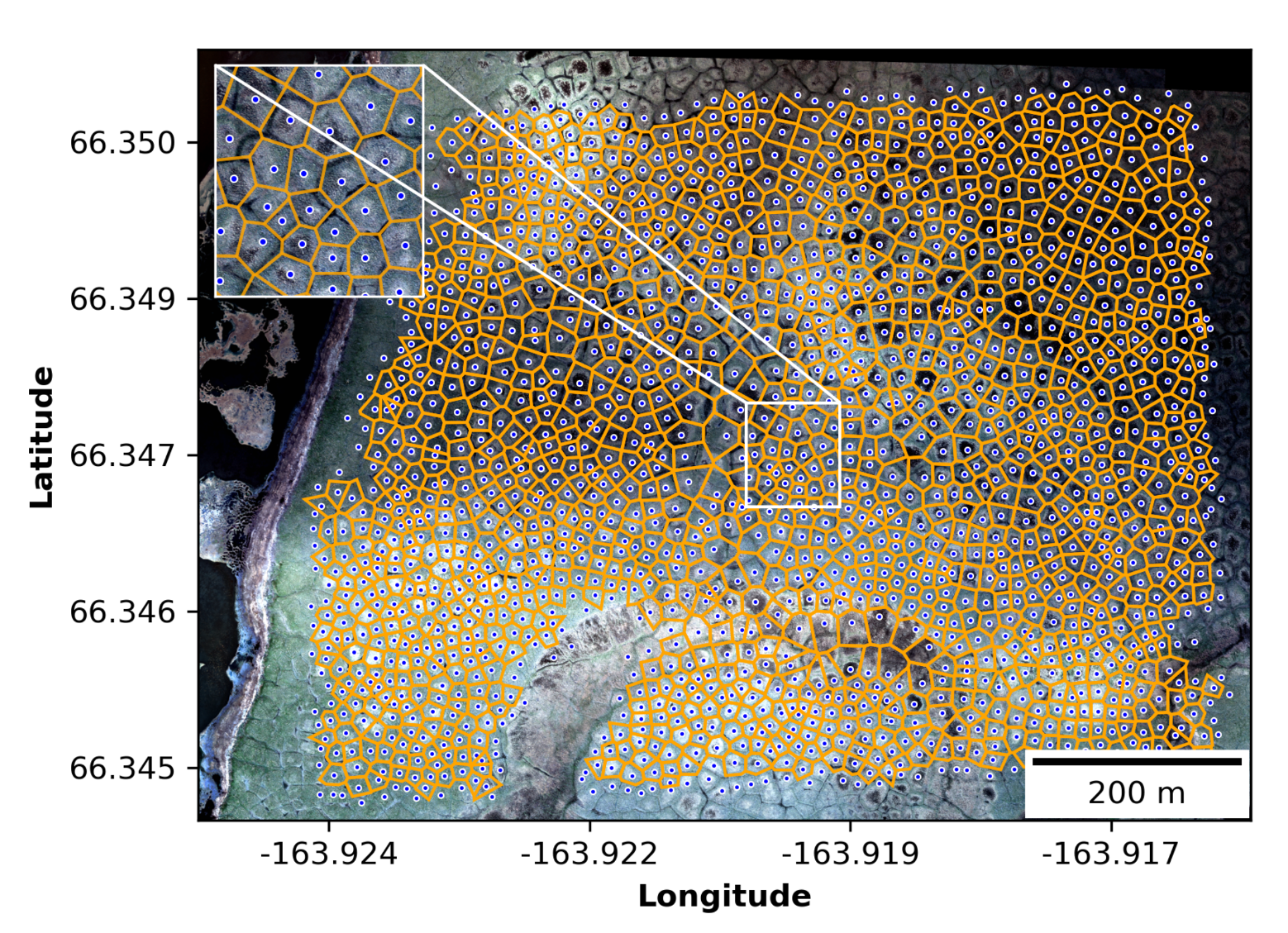

Fig 2: This figure from the study shows an aerial view of Cape Blossom overlaid with Voronoi diagrams derived from clustered volunteer-contributed ice-wedge polygon center points

The Study: two Arctic regions, 105 Volunteers, thousands of polygons

The study focused on two Arctic regions: Cape Blossom in Alaska (USA) and Blueberry Hills in Canada. Using a web-based mapping app, volunteers (many of whom had contributed by joining our organized mapping events) clicked their way through high-resolution imagery, marking the centroids of ice-wedge polygons. The imagery of Blueberry Hills had been collected with help from school students in Aklavik, NWT, Canada using consumer-grade drones.

Then, researchers used the crowd-sourced centroid data to reconstruct the ice-wedge polygon networks with Voronoi diagrams, enabling the extraction of important geomorphological (e.g., polygon area, perimeter) and hydrological (e.g., network topology, betweenness centrality) parameters. Knowing these parameters is valuable for researchers as they can be used to gather insights into past and current changes in the permafrost landscape.

So… Did the crowd get it right?

Short answer: Yes, and impressively so.

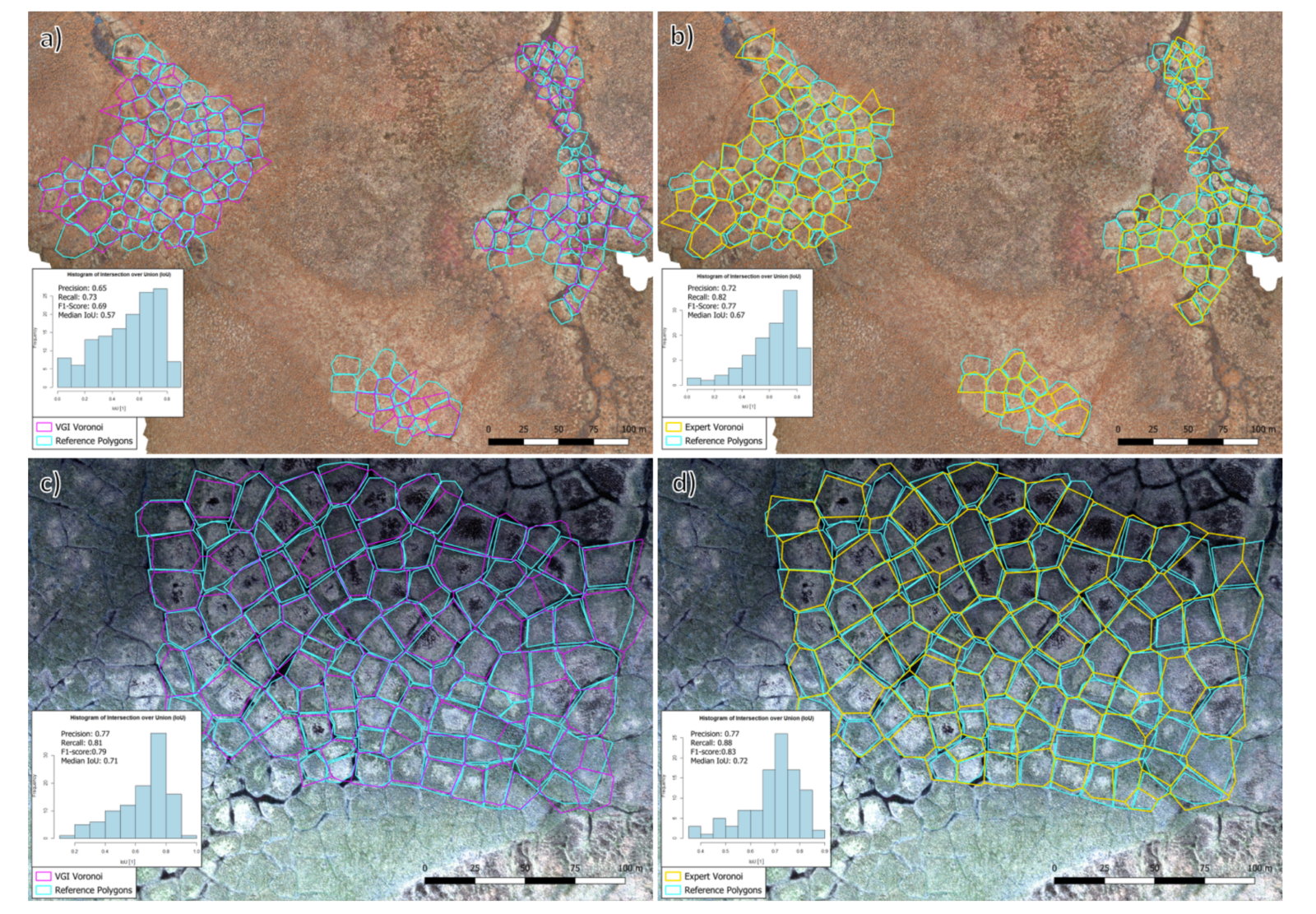

We assessed the quality of volunteer contributions by comparing their completeness and accuracy with contributions made by experts. Results showed that the quality of volunteer contributions closely matched the experts´ work quality. Only in areas with complex landscapes and irregular polygon morphology did their contributions tend to deviate from the researchers. However, the overall results demonstrate that non-experts are very capable of contributing valuable spatial data. To put some numbers on it:

- Volunteer data achieved high completeness (88.74% in Cape Blossom and 70.81% in Blueberry Hills) and high positional accuracy (with median deviations of just 1.29 m and 1.38 m respectively).

- The study found that around five volunteers per polygon were needed to provide sufficient data reliability.

In other words: citizen scientists, equipped with an intuitive interface and good guidance, can map the permafrost polygons with skill comparable to trained specialists. This means that scalable, reliable permafrost monitoring can be done also without expensive elevation data, leveraging the power of the crowd.

Fig 3: This figure from the study shows a visual comparison of crowdsourced data and data compiled by experts: (a) VGI-derived polygons at Blueberry Hills. (b) Expert-derived polygons at Blueberry Hills. (c) VGI-derived polygons at Cape Blossom. (d) Expert-derived polygons at Cape Blossom.

Citizen Science matters more than ever

Volunteered geographic information (VGI) can provide a scalable way to fill gaps where high-resolution elevation data for detailed landscape modeling is scarce, such as in the Arctic. Using VGI allows for more “eyes” on the landscape, and more data to understand how permafrost landscapes are changing. It also enables the public to directly connect with research efforts.

The UndercoverEisAgenten project, launched in 2021 through a collaboration between Heidelberg Institute for Geoinformation Technology (HeiGIT), the German Aerospace Center (DLR), and the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, showed students and volunteers that they can contribute to real-world science. Through educational outreach, drone flights, and hands-on mapping, young people contributed to map Arctic landscapes and learned about the consequences of climate change in permafrost regions.

This project showed us how the “power of the crowd” can effectively support VGI-based research, even in remote places such as the Arctic.

Fig 4: The research team flew drones together with school students to collect aerial imagery of permafrost landscapes as part of the UndercoverEisAgenten project (Credit: Christian Thiel)

Further reading

- the UndercoverEisAgenten project webpage: https://heigit.org/undercovereisagenten/

- a blog post on the launch of the crowdsourced mapping app: https://heigit.org/launch-a-new-online-mapping-application-helps-undercovereisagenten-on-the-trail-of-permafrost/

- another blog post with a video on the field mission to Aklavik, Canada: https://heigit.org/chasing-permafrost-insights-from-the-aklavik-expedition/

This blog post is associated with a recent publication in The Cryosphere:

Walz, P., Fritz, O., Marx, S., Mueller, M. M., Thiel, C., Lenz, J., Kaiser, S., Frappier, R., Zipf, A., and Langer, M. (2025). Monitoring Arctic Permafrost – Examining the Contribution of Volunteered Geographic Information to Mapping Ice-Wedge Polygons, The Cryosphere, https://tc.copernicus.org/articles/19/6355/2025/