This miniseries features the tradition of ‘PhD hat’ making in German research institutes and universities. For those of you unfamiliar with this idea (as I once was), this is one of the final milestones a graduate student has before they are officially a “Dr.”. Upon the successful defense of a thesis, the labmates of the PhD student craft a graduation hat from a mishmash of scrap cardboard and memorabilia. Hours of work go into these beloved pieces, and you can often find these hand-made creations fondly perched on a shelf in faculty’s offices. Here, we talk with several researchers who work within the cryosphere sciences to get a tour of their PhD hats. In the last posts, we ‘herd’ about Torben’s arctic herbivore hat, took a tour of the Nitrogen cycle with Tina through her microbiology hat, and last month we explored the Siberian alaas landscape through time with Izabella and Ramesh’s hats. This month we hear from an ice core researcher who traveled far from home for her PhD, but brought the tradition of the ‘PhD Hat’ with her.

Dr. Dorothea Moser (she/her) is a glaciologist who studies past climates through ice-cores collected in both the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets. Her thesis “Advances in Understanding Melt Affected Firn and Ice Cores from the Polar Regions” explored how ice core melt can alter, but often always destroy, the records of earth’s environmental conditions within the layers of ice. As a PhD student, Dorothea was affiliated with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the University of Cambridge, though her career in the cryospheric sciences began much earlier in Bremerhaven, Germany at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI).

Dorothea’s first encounter with the world of ice core research was during an internship supervised by Dr. Johannes Freitag at the AWI in 2015. Her time as an undergraduate student was the start of an academic path that got her ‘hooked on the Arctic’. Fast forward to the present, and we meet Dorothea for this interview just days after she successfully defended her PhD thesis this May (2025).

In this installment of the Cryospheric Caps miniseries we hear how Dorothea brought both her ice-core expertise and the tradition of ‘PhD Hat’ making with her to the United Kingdom from her home country of Germany.

Hi Dorothea, can you tell us about how you found your PhD research topic?

During my masters work, I worked with a firn core from Young Island (Southern Ocean). It was 17 meters long so it was rather short but very interesting. Immediately, I noticed that it had lots of peculiar structures.

Not to be confused with the green and leafy ‘fern’ plants, glaciologists use the word ‘firn’ to describe an accumulation of snow, compressed over at least one melt season. Firn becomes more dense from the weight of the layers of snow above it, and with time forms the vast layers of glacial ice that make up the world’s ice sheets.

For this core, I had tried to create an age scale and present the proxy data in that core. However, I encountered a mess! Many of the classical tools or methods for deciphering core age (such as stable water isotopes) proved difficult because the melt had diminished the strength of the signal or dissolved and washed away the soluble impurities. During my masters I had tried to make sense of this, but I knew that I didn’t have enough time to solve this riddle of melt-affected firn and ice entirely. That led me to design this PhD project with my masters supervisor, who then supervised my PhD – Dr. Liz Thomas. From both my bachelors and masters work I felt like I had already had some ‘tools’ to shed new light on the challenge of making sense of melt-affected ice core profiles. So, that’s what I did!

What were the main findings of your PhD thesis?

One message I’d like to get out to the world is that melt-affected firn and ice cores are not a lost cause!

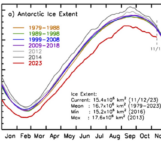

These melt-affected firn and ice cores have lots of remaining questions about how we can best utilize them. A key message from my research is that we already have some good tools. In my work I utilized structural investigations, experiments in the field (Figure 1), and other high-resolution chemistry measurements. Such methods are definitely worth looking into, rather than considering a melt-affected core unusable.

Can you tell us about your PhD hat?

I wasn’t sure what the graduation traditions at BAS were at first, and I knew of the PhD hat tradition and had thought to myself ‘What would my hat look like?’. My boyfriend (also originally from Germany) knew of the PhD hat tradition and picked up on this. He and my mom worked on a hat together as a surprise for the day of my defense. I would say my ‘PhD hat’ reflects the German academic roots that I have, but also my family connections (Figure 2).

Moving to another country for your PhD means stepping into a different world to some degree. To see these worlds come together on the day of my defense was just really beautiful.

Figure 2: Dorothea on the day of her defense with her PhD Hat. The polar bear on top of the hat, as well as the icicles and snowflakes around the edges of the hat symbolize her work in the polar environments. [Credit: Dorothea Moser]

What traditions do PhD students at the British Antarctic Survey have to mark the end of their time as PhD students?

The tradition at BAS is to give the graduate a map related to their field site (Figure 3). Our Mapping and Geographic Information Centre – which is an absolute treasure – creates high resolution maps of wherever our researchers are traveling. One of these past expedition maps will be chosen by your peers, and hidden in a ‘secret’ room (so that the soon-to-be-graduate can not see the map before the day of the defense). A couple of weeks before the defense emails will get sent around to the team letting them know where the map is so that everyone has the chance to sign it, if they have something to add. Usually it’s messages of congratulations, and celebrating their achievements.

Figure 3: Left: Dorothea’s map of the Arctic signed by her team and colleagues in her home in the UK. [Credit: Dorothea Moser]. Right: Dorothea in the midst of her PhD field work in Svalbard. Here she investigates a firn core, and how the dye she applied had seeped through the structure of snow and ice [Credit: Iain Rudkin]

Do you plan to keep working within the cryosphere after your PhD?

I am! I’ll soon start a postdoc at the BAS. In this role, I’ll be studying the ability of firn on ice shelves to retain melt water and buffer sea level rise, or in other words the ‘sponginess’ of the ice shelves.

I’ll continue working with the team at BAS analyzing firn cores from an Antarctic ice shelf, and now also working with collaborators who use remote sensing techniques and model larger scale processes on ice shelves. I think it will be really cool to bring some of my expertise in ‘ground truthing’ methods that I’ve gathered over the last few years to a modeling project that has vast societal implications in terms of contributing to estimates of sea level rise.

Do you have any words of wisdom for current graduate students who are preparing for their own defenses?

Sometimes we hear ‘oh, finishing a PhD is so hard, and it can break you’ or similarly fearsome messaging. While I want to acknowledge that some journeys are really hard, especially at the end, I think that it’s worth telling each other that it doesn’t have to be that way. When you’re on the home stretch, you’ve already done the majority of the work, and losing your sanity won’t lead to the productivity that gets you across the finish line. My experience has been that a support network that helps you to see that the bigger picture is crucial.

Against this background, my words of encouragement to others would be that it’s okay if you don’t read your thesis 50 more times before you submit. It’s also important to take a breather in the last few days, and reflect on the journey you’ve already made to get there.

Thank you for your time Dorothea, and for taking us on a tour of your PhD hat (and map).

Readers, stay tuned for the next instalment of this miniseries, in which we will take another tour of the cryosphere through the PhD hats of those studying our icy planet.

Further Reading

- Looking for a way to stay connected to this topic? Dorothea is active on Bluesky as @heartmeltingice.bsky.social and on her personal academic webpage.

- You can also check out some publications that Dorothea (co-)authored recently:

- If you would like to learn more about Dorothea’s life during field work, check out her recent interview with Carbon Brief “Svalbard” Can Scientists salvage climate data from rapidly melting glaciers”

- If you haven’t read them yet, check out the other episodes of this miniseries “Cryosphere Caps: PhD hats and the researchers that wear them”

- Episode 1: The arctic herbivore hat of Torben Windirsch

- Episode 2: The microbial ecology hat of Tina Sanders

- Episode 3: The alaas landscape hats of Izabella and Ramesh

Edited by Lina Madaj