In November last year (see this post), we promised to provide you an update of what happened with Antarctic sea ice during the year 2023 – a year of an exceptionally low extent. In this post, we try our best to discuss the conditions that lead to (part of) the recent loss in Antarctic sea ice, including atmospheric and ocean processes.

How sea ice usually works…

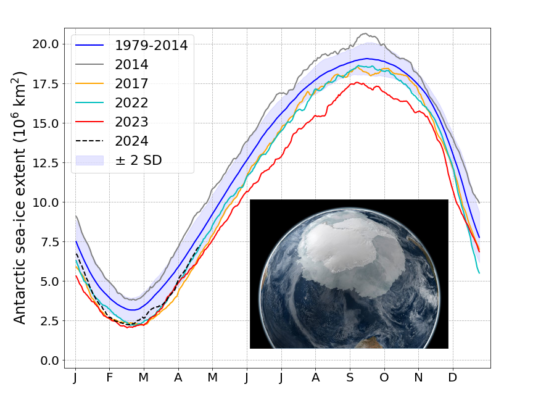

One of the ways scientists have to monitor the state of Antarctic sea ice is by measuring its extent, using satellite data (typically defined by an area with at least 15% sea-ice concentration; more details in this post). Much like in the Arctic, Antarctic sea-ice extent displays a strong seasonal cycle, except that the minimum occurs in February, at the end of the austral summer, and the maximum is in September, at the end of the austral winter (you can find a little recap in this previous post). This seasonal cycle can be seen in Figure 1.

… and what is different now

In that figure you can see that Antarctic sea-ice extent was exceptionally low throughout 2023 (red curve) compared to the mean extent between 1979 and 2014 (blue curve). After an already low extent through the entirety of 2022 (cyan curve), the minimum sea-ice extent of 2023 (occurring in February) reached a value of around 2 million km² (an area that is similar to countries such as Saudi Arabia and Mexico for example). This is the lowest minimum sea-ice extent on record.

Although slightly larger in extent, the minimum values of 2017 (orange curve), 2022 (cyan curve) and this year (2024; black dashed curve) complete the list of the four recent record lows. These record lows are particularly striking as they come after a period of small increase in the minimum sea-ice extent between 1979 and 2014.

A recovery that never occurred

Beside the record low sea-ice extent in February, what is really surprising for 2023 is that also sea-ice growth after that minimum was much lower than usual. During the growth season, which always follows the summer minimum and goes from March to September, new sea ice forms due to the cold conditions: this is a chance for sea ice to recover to “normal”, but this did not happen during 2023.

As a consequence, the maximum sea-ice extent of 2023, which occurred in September (at the end of the growth season), was 1 million km² below 2017 and 2022 and 1.5 million km² below the mean over 1979-2014 (red curve in Fig. 1). The situation did not improve after that, and overall, the year 2023 remained well below the average for the entire year. But what processes led to make 2023 such an exceptional year?

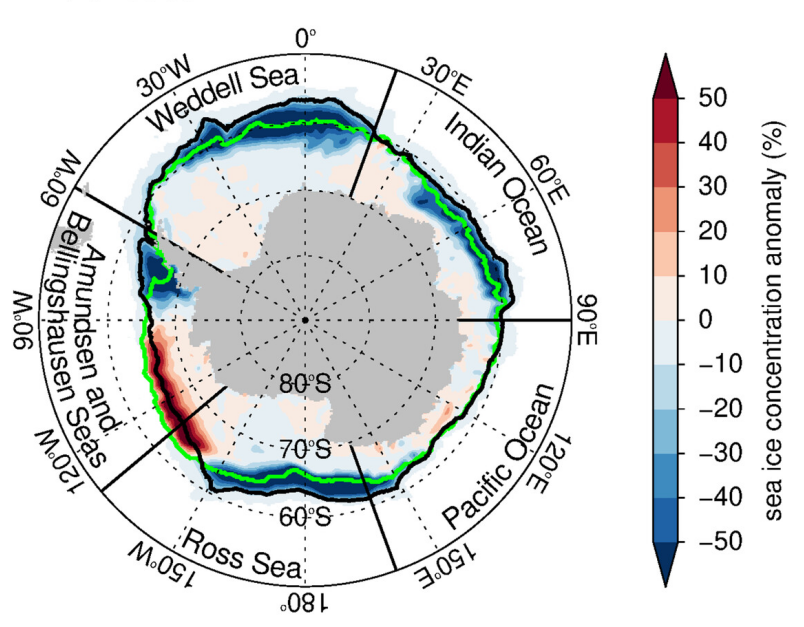

Figure 2: Antarctic sea-ice concentration anomaly in July 2023 compared to the average (1979-2023) based on OSI SAF data. Blue (red) areas show regions where sea-ice concentration in 2023 was lower (higher) than average [Credit: Figure 2b of Gilbert & Holmes (2024)].

What happened in 2023?

Until recently, the different sectors of the Southern Ocean around the Antarctic continent experienced contrasting changes, with some regions even showing an increase in sea ice, and other regions showing a decrease (see this post). However, in 2023 the picture was different: since April 2023, sea-ice extent was below average everywhere except in the Amundsen Sea (Figure 2). Thus, sea ice decreased at a hemispheric scale last year. There were probably many reasons explaining the low sea-ice extent in 2023, but both atmospheric and ocean conditions have probably played a key role.

Was the atmosphere the culprit?

Atmospheric circulation strongly controls Antarctic sea ice (we talked a bit about it in this post). In particular, the Amundsen Sea Low, which is a low-pressure system forming close to West Antarctica, was unusually deep (meaning it was reinforced!) and far to the east. In these conditions, northerly winds transported warm air and pushed the ice to the coast (friendly reminder: low-pressure systems spin clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere), so the growth of sea ice in winter was limited.

Was it the ocean?

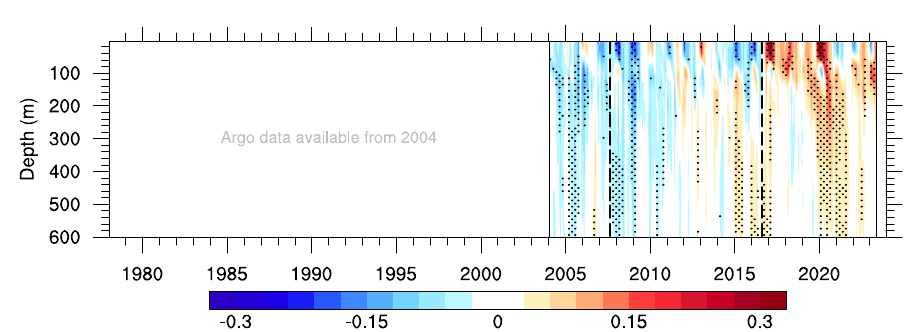

The ocean has also probably contributed to the 2023 exceptional year. A new study shows that the recent warming of the Southern Ocean, especially at depths below 100 m, also explains part of the drop in Antarctic sea ice since 2016. In Figure 3, we can see the warming of the ocean below 100 m starting around 2015, a bit before Antarctic sea ice starts to decline in 2016-2017. The role of the ocean has been confirmed for 2016, and it possibly also contributed to 2023…

Figure 3: Southern Ocean (50-65°S) temperature anomaly from 2004 to 2023 (in °C) compared to the average (2004-2022) for all depths between the ocean surface and 600 m, based on Argo data. Red (blue) indicates where ocean temperature is higher (lower) than average [Credit: Figure 1c of Purich & Doddridge (2023)].

Or was it the preconditioning?

The year 2023 follows a previous record low in 2022 – having started with a lower-than-usual sea-ice extent. Thus, a hypothesis is that part of the reason explaining the low sea-ice extent of 2023 is due to the low starting point in 2022. Whether this “preconditioning” is a relevant factor for this and future years still needs to be assessed…

In summary, all three factors (atmospheric circulation, ocean temperature at depth and preconditioning) might explain the exceptional Antarctic sea-ice extent in 2023.

The future of Antarctic sea ice is uncertain

It is clear that global warming has had a major impact on Arctic sea ice. This is less clear for the Antarctic, which has shown a lot of variability over the years. What we do know is that the previous 7-8 years have been relatively unusual for Antarctic sea ice since the beginning of satellite observations in 1979, with four record lows in a short time window.

The question is whether 2024 will present a low sea-ice growth and follow 2023, or will come back closer to the average, as 2017 and 2022 did. Yet, it is a difficult question to answer at the moment, as many climate parameters interact with each other. In the long term, there is a chance that Antarctic sea ice will follow a trend that resembles more what happens in the Arctic. That is why research is highly needed to try to better understand the causes of the ongoing changes. Whatever the case, count on us for a new blog post in the future!

Further reading

- EGU Cryoblog post by D. Docquier (2023) about the state of Antarctic sea ice in 2023.

- EGU Cryoblog post by Q. Dalaiden and B. Mezzina (2022) about the impact of wind on Antarctic sea ice.

- EGU Cryoblog post by R. Frew (2017) about the small increase in Antarctic sea ice.

- Article by E. Gilbert and C. Holmes (2024) explaining the record low of 2023.

- Article by B. Mezzina et al. (2024) explaining the contributions of the atmosphere and ocean to the drop in Antarctic sea ice in 2016.

- To get a daily update of Antarctic sea-ice extent: NASA, Current State of Sea Ice Cover and NSIDC, Charctic Interactive Sea Ice Graph (click on “Antarctic”).

- Carbon Brief article about Antarctic sea ice in 2023.

Edited by Emma Pearce and Maria Scheel