The cold icy surface of a glacier doesn’t seem like an environment where life should exist, but if you look closely you may be surprised! Glaciers are not only locations studied by glaciologists and physical scientists, but are also of great interest to microbiologists and ecologists. In fact, understanding the interaction between ice and microbiology is essential to fully understand the glacier system!

Why study micro-organisms on glaciers?

Micro-plants, micro-animals and bacteria live and reproduce in cryoconite ecosystems on the surface of glaciers. Cryoconite is a dark coloured material (Fig. 2) found at the bottom of cylindrical water-filled melt holes (cryoconite holes) on a glacier surface; it consists of dust and mineral powders transported by the wind, and micro-organisms. Cryoconite holes are formed as the dark coloured material causes localised melting, due to reduced albedo (ability of a surface to reflect solar energy).

Figure 2: Example of a Cryoconite hole filled with dark cryoconite material (markers are 10×10 cm) [Credit: Tommaso Santagata – La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche]

Cryoconite ecosystems are very isolated and must work together to survive and thrive. Some micro-organisms (e.g. micro-algae) can photosynthesise and are able to live autonomously inside cryoconite holes using atmospheric carbon dioxide, sunlight, water and chlorophyll. By this same mechanism, they can find all the molecules essential for their vital and structural needs and consequently they generate most of the molecules necessary for all other living things. For example, the waste product of photosynthesis, oxygen, is essential for the survival of all organisms living in aerobiosis in these communities. Due to their key role in the ecosystem, the micro-algae are known as “primary producers”.

As around 70% of the earth is covered in water, which is colonised by micro-algae, studying the way they survive in extreme conditions and how they contribute to the ecosystem is of global importance – especially at this time of climate change.

The diversity of highly active bacterial communities in cryoconite holes makes them the most biologically active habitats within glacial ecosystems.

Data collections – Six days on THE glacier

The Perito Moreno glacier (Fig. 3) is known as one of the most important tourist attraction in Argentinian Patagonia (see our previous IOW post). Each day, hundreds of people observe the impressive front of this glacier and wait to see ice detachments and hear the loud sound of it’s impacts in the water of Lake Argentino. The glacier takes it’s name from the explorer Francisco Moreno, who studied the Patagonian region in the 19th century. The glacier is more than 30 km in length and an area of about 250 km2, Perito Moreno is one of the main outlet glaciers of Hielo Patagonico Sur (southern Patagonia icefield).

Figure 3: Aerial view of the Perito Moreno

[Credit : Tommaso Santagata – La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche]

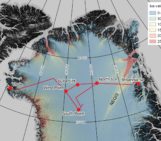

In April 2017, after several missions to the Greenland Ice Sheet to study extremophilic micro-organisms (organism that thrive in extreme environments) of ice, a team of Italian and French scientists organised a scientific expedition to study the microbiology of Perito Moreno. The expedition was organised by La Venta and Spélé’Ice and included researchers from several French and Italian Universities (see below for full list)

Perito Moreno is very well known, especially to the La Venta team, who have been organising scientific expeditions in Patagonia since 1991. The microbiological research objectives of this mission were to study the micro-organisms that live on the surface of Perito Moreno and compare them to results obtained in the other polar, sub-polar and alpine regions. The multi-disciplinary research team were able to set up a complex field laboratory, which included a microscope and an innovative small tool size capable of DNA sequencing. This meant that samples could be analysed immediately after their extraction from the ice (Fig. 1).

Getting all the equipment and personnel to achieve this expedition onto the ice was not an easy task. The team and their equipment were transported by boat to a site near the front of the glacier. Equipment then needed to be transported to the Buscaini Refugee, a shelter used as a base-camp by the team (Fig. 4). This took two trips, on foot, of about 7 hours (12 km of trail along the lateral moraine and the ice of the glacier with very heavy backpacks) – not an easy start! Luckily this hardship was somewhat mitigated by the absence of extreme cold, in fact, abnormally hot weather tallowed the team to move and work in t-shirts – not bad!

Figure 4: Walking into the field site along the ice of Perito Moreno – part of the 12km of trail to the Buscaini Refugee shelter

[Credit: Alessio Romeo – La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche]

Thanks to these favourable weather conditions, all the goals were achieved in the short amount of time the team were allowed to camp on the glacier (special permission is needed from the national park to do this). During the five days of activity, many samples were taken and sequenced directly at the camp by the researches. Other important goals, such as morphological comparisons and measurements of the velocity of the glacier through the use of GPS, laser scanning and unmanned aerial vehicles were achieved by another team of researchers (stay tuned for another blog post about this!).

Universities and research institutes involved: University Bicocca of Milan – Italy, University of Milano – Italy, Sciences of the Earth A.Desio – Italy, Natural History Museum of Paris – France, University Diderot of Paris – France, University of Florence – Sciences of the Earth – Italy, University of Bologna – Italy.

Further Reading

- La Venta Blog – First news from Perito Moreno

- Franzetti, Andrea et al. (2017), Potential Sources of Bacteria Colonizing the Cryoconite of an Alpine Glacier, PLoS ONE

Edited by Emma Smith

Tommaso Santagata is a survey technician and geology student at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. As speleologist and member of the Italian association La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche, he carries out research projects on glaciers using UAV’s, terrestrial laser scanning and 3D photogrammetry techniques to study the ice caves of Patagonia, the in-cave glacier of the Cenote Abyss (Dolomiti Mountains, Italy), the moulins of Gorner Glacier (Switzerland) and other underground environments as the lava tunnels of Mount Etna. He tweets as @tommysgeo

Tommaso Santagata is a survey technician and geology student at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. As speleologist and member of the Italian association La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche, he carries out research projects on glaciers using UAV’s, terrestrial laser scanning and 3D photogrammetry techniques to study the ice caves of Patagonia, the in-cave glacier of the Cenote Abyss (Dolomiti Mountains, Italy), the moulins of Gorner Glacier (Switzerland) and other underground environments as the lava tunnels of Mount Etna. He tweets as @tommysgeo