How did we (nearly) all forget about, or simply overlook, a large-scale two-year long mid-20th Century scientific expedition to the northern Greenland Ice Sheet? Particularly an expedition that kick-started some significant glaciological and geophysical careers, developed large-scale polar logistical capabilities, traversed the ice sheet, acquired some novel and critical data, and asked some big research questions about the glaciology of the Greenland Ice Sheet? Somehow, many of us did. It is now time to reinvigorate our lapsed memories. Come with me and (re-)discover the British North Greenland Expedition thanks to a cardboard box full of what appeared, from the surface, to be some rather nondescript rolls of yellowed paper. As the old adage goes, never judge a ‘book’ (or an ice sheet) by its cover.

It all started in a second-hand bookshop…

Like all good stories, this one begins in a second-hand book shop, perhaps best known for its re-discovery of the famous slogan ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’, and continues with a sequence of remarkable serendipitous events. In 2011 I stumbled, in that book shop in northeast England, across a book with an enigmatic midnight-sun silhouetted photo of a pyramid tent surrounded by what appeared to be boxes of scientific equipment and a field scientist on its cover. The book, ‘High Arctic’ (Banks 1957; see Figure 2), told “The story of the British North Greenland Expedition” that took place 1952-54. Like many I have spoken to since, my knowledge of that expedition before that time was non-existent or very limited. After reading the book, however, I was absolutely transfixed, and frankly bemused that so many cryosphere researchers and so many polar historians seem have nearly totally forgotten about such an important and large-scale joint scientific and military expedition to North Greenland. Here, I hope to share my excitement and passion for that expedition, as well as convey the scientific and historical importance of the British North Greenland Expedition (BNGE), and the longer impact of the expedition members and the datasets they acquired. In short, I want to share the story of my (re-)discovery of the expedition and perhaps help to reinvigorate the significance of the BNGE in the pantheon of important large-scale polar scientific research expeditions of the 20th Century.

Figure 2. A selection of the surprisingly few books written about the British North Greenland Expedition. [credits: Neil Ross]

Glaciological equivalent to the ‘Dead Sea Scrolls’?

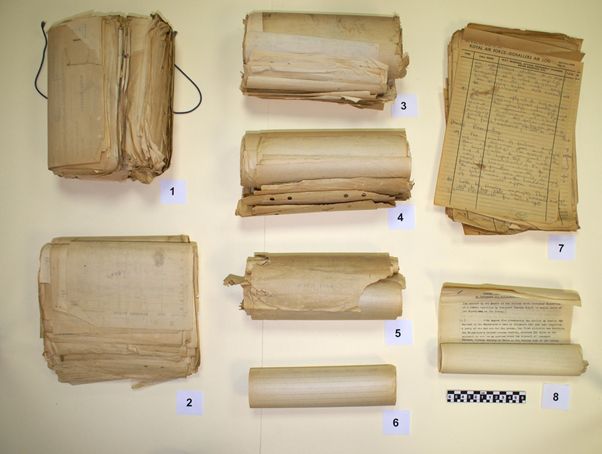

Fast forward to 2013, and I had recently started as a Lecturer in Physical Geography at Newcastle University. Chatting with our head technician at the time, Rupert Bainbridge, about glaciology ‘kit’ and past glaciological research in the department, Rupert revealed that there was a cardboard box of potential interest in his office. Well, what a cardboard box this turned out to be. The box itself was intriguing enough, postmarked 1967, with ‘from’ stamps from the ‘Blue Ice’ research project at the Inge Lehmann seismological station in Greenland, and a United States Air Force delivery address in Texas. In the box, was something very exciting: five Dead Sea Scroll-like yellowed rolls of paper tied with string (Figure 3). A rapid and careful scan of a sample of the documents revealed some familiar scientific names from ‘High Arctic’ (i.e. Stan Paterson, Hal Lister, Colin Bull, ‘Duggie’ Peacock, and Malcolm Slesser), demonstrating that these were records from the BNGE. It was quickly obvious that these were pencil-written records of radio transmissions: (i) between the field stations of the BNGE (i.e. Britannia Sø and North Ice); and (ii) from Britannia Sø (‘lake’ in Danish) to the UK and to the US military base at Thule. Therefore, what was lying on a shelf in an office in Newcastle were detailed (near-)real-time raw unexpurgated accounts of the BNGE from 1952-54, clearly historically significant but in rather fragile condition. As you can probably imagine, this historical treasure trove rather piqued my interest, and I wanted to find out more.

Figure 3. The radio transcripts of the British North Greenland Expedition before conservation [credits: Tyne and Wear Museums]

The importance, impact, and legacy of the British North Greenland Expedition

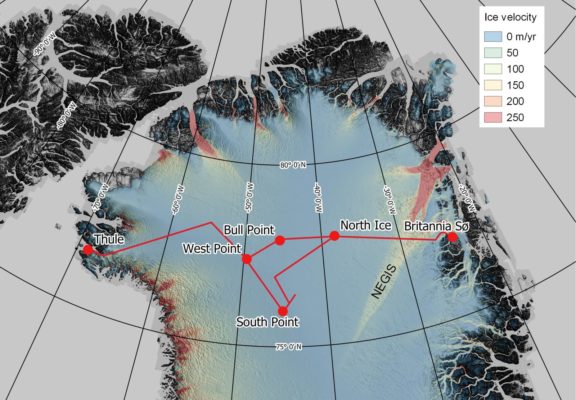

The BNGE explored and traversed north Greenland from Dronning Louise Land in the east to Thule in the west. The expedition had wide-ranging aims and objectives, including geological mapping, ice sheet history, topographic surveying, meteorology, polar medicine and polar logistics (Hamilton, 1952). The glaciological aims were “A study of surface conditions of the ice sheet and of two outflowing glaciers” (Lister, 1952), with a geophysical team tasked with determining ice sheet thickness (Hamilton, 1952). The expedition had two field camps: (i) at Britannia Sø, a lake between the Storstrømmen and Britannia glaciers; and (ii) North Ice in the interior of the ice sheet, just west of the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream. The former was later destroyed by a glacier surge in the early 1970s, whilst the latter was buried by snow accumulation. An oversnow traverse of surface elevation and gravity measurements was completed between the camp at Britannia Sø all the way to Thule air base, via North Ice (Figure 1). Seismic measurements of ice thickness were also undertaken, but these did not extend to Thule, with the seismic team looping back to North Ice and Britannia Sø before extraction from the field. The logistics involved in the expedition were very ambitious, with input and movement of personnel, equipment and supplies by ship, float plane, ice sheet airdrops, dog sleds and motorised oversnow vehicles adapted from WWII-era tracked vehicles (‘Weasels’).

Anyone who has been fortunate enough to participate in polar scientific field research knows that the most important aspect of any field campaign is the people involved. The BNGE was no different. Many of the scientific team on the expedition became leaders in their respective fields. From a glaciological perspective perhaps the most widely known member of the team is Stan Paterson (yes, the Stan Paterson of ‘The Physics of Glaciers’!). However, from a personal perspective the team member of most interest was Hal Lister, an undergraduate student at Newcastle University a few years before the expedition and an academic staff member for ~30 years afterwards. Hal is potentially of wider importance too – aside from his research work, I suspect that Hal may have been the first person (or at least one of the first) to overwinter on both the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (at ‘North Ice’ in Greenland and ‘South Ice’ in Antarctica), having participated in both the BNGE and the later Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1957-59 co-led by Vivian Fuchs and Edmund Hillary. Hal must also have been one of the few people on Earth ever to have oversnow traversed the NE Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS) as well as Byrd, Support Force, Academy and Recovery glaciers in Antarctica. At Newcastle, Hal was an enthusiastic facilitator of student fieldwork expeditions across the globe (e.g. to the Afghan Hindu Kush (Horsley, 2021)), a tradition facilitated by the Newcastle University Expeditions Committee that supports and funds undergraduate overseas expeditions to this day.

The BNGE was an important test of British polar capabilities in the early 1950s, in terms of military operations and logistics, and polar medicine. From a cryosphere perspective however, it was also a test of British polar research capabilities. The model of operations (e.g. ships, aircraft, motorised cross-ice sheet vehicles) and data collection (e.g. seismic and gravity measurements of ice thickness, mass balance observations) was one that later echoed in both the international oversnow Antarctic International Geophysical Year (IGY) traverses (between 1957 and 1966) and the Commonwealth Trans Antarctic Expedition (1955-58). The BNGE was therefore one of a series of important ‘stepping stones’ between early polar exploration and modern day polar field research. You could argue that you can trace the DNA of the BNGE all the way through to large-scale modern polar research programmes such as the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. There is little doubt that important polar logistical and operational lessons were learnt from the BNGE, even if the expedition itself has been somewhat forgotten.

The legacy of the BNGE extends beyond people and logistics however. The data and research findings of the expedition (Hamilton, 1958, and references therein) have been used for longer term quantification of ice sheet elevation change in northwest Greenland (Paterson and Reeh, 2001), and many of the scientific questions generated by the research are still highly relevant today. For example, in 1958 Hal Lister posed the following two questions: “What is the state of the balance-sheet of glaciers that flow from the huge Greenland ice-sheet? What changes have taken place and what meteorological factor if any is dominant in these changes?” (Lister, 1958). Expedition field measurements (e.g. ice thickness from the seismic surveys) can be found within the radio transcripts, but in some cases important field data from the expedition seems to sadly have been lost. Mass balance measurements were undertaken at Admiralty and Britannia Glaciers between 1952-54 (Machguth et al., 2016); however, some of these observations have not (yet) been located. Intriguingly, the expedition also traversed NEGIS several times. NEGIS, one of Greenland’s largest ice streams, has been the focus of multi-national glaciological research in recent years (e.g. the East Greenland Ice-core Project (EastGRIP)) due to its potential instability in response to climate warming and subsequent sea level contribution. It may be that important insights into the longer-term history of NEGIS could be gained from BNGE records here in Newcastle, or wherever else they turn up. Important insights have been gained in Antarctica through comparison of US ice thickness traverse measurements from the early 1960s with modern-day observations (Smith et al. 2012).

From a geopolitical perspective, the timing of the BNGE is also intriguing, given that it occurred in a post-WWII context associated with the end of the British Empire and the early parts of the Cold War. With regards to the latter, military experience of operating in Arctic environments was an important outcome gained from the expedition, particularly for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Aside from the geopolitical and operational aspects, the BNGE radio transcripts provide detailed un-filtered insights into day-to-day events on the expedition, interactions between BNGE expedition members, as well as the challenges of undertaking research in remote polar environments. They even contain an early-career post-expedition job request for Stan Paterson to work up the expedition data at Cambridge University. In addition, however, the transcripts also reveal the impacts of the sadder and more dangerous aspects of polar expeditions, such as the death of Danish team member Captain Hans Jensen during a mountain descent, and an aircraft crash at North Ice that injured several members of the aircraft crew.

Conserving, enhancing and making accessible the expedition records

But what about the delicate pencil-written paper radio transcripts I hear you ask? Thankfully due to the considerable efforts of Ian Johnson, the Head of Special Collections in the Newcastle University library, conservators from the Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums, and a generous grant from The National Manuscripts Conservation Trust in the UK, these transcripts have now been conserved and enhanced, stored in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment, and have been digitised. As a result, these wonderful records of an important mid 20th century Arctic expedition are preserved and accessible for further research and investigation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The radio transcripts of the British North Greenland Expedition after conservation [credits: Tyne and Wear Museums]

Further reading

- Banks (1957). High Arctic. The Story of the British North Greenland Expedition. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London. pp. 276, DOI:

- Hamilton (1952). The British North Greenland Expedition, 1952-54. Nature 169:727-728, DOI: 10.1038/169727a0.

- Hamilton (1958). The British North Greenland Expedition, 1952-54, Scientific Results. Nature 181:1030-1032, DOI: 10.1038/1811030a0.

- Lister (1952). British North Greenland Expedition summary of glaciological programme. Journal of Glaciology 2:110.

- Lister (1958). Glaciology (1): The balance sheet or the mass balance. From Venture to the Arctic. Edited by R.A. Hamilton, Penguin Books, 167-188.

- Horsley (2021). The Afghan Hindu Kush in 1965: A research expedition of the international hydrological decade. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal pp. 80. https://lib.icimod.org/record/35241.

- Machguth et al. (2016). Greenland surface mass-balance observations from the ice-sheet ablation area and local glaciers. Journal of Glaciology 62:861-887, DOI: 10.1017/jog.2016.75.

- Paterson & Reeh (2001). Thinning of the ice sheet in northwest Greenland over the past forty years. Nature 414:60-62, DOI: 10.1038/35102044.

- Smith et al. (2012). Rapid subglacial erosion beneath Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters 39:L12501, DOI: 10.1029/2012GL051651.

Edited by TJ Young and Giovanni Baccolo

Neil Ross is a Senior Lecturer in Physical Geography at Newcastle University, UK. His research interests include ice sheets, glacier geophysics, ice sheet hydrology and subglacial lakes, ice mass reconstruction, near-surface geophysics, pingos, and many other things. On the evidence of this blog, Neil has, through a seemingly random series of serendipitous events, apparently developed a nascent and unanticipated interest in ‘histo-glacio’ research. He (these days rather occasionally) tweets at @sledge_ross, very much hopes one day to recover his EU citizenship, and can be contacted at neil.ross@ncl.ac.uk.

Neil Ross is a Senior Lecturer in Physical Geography at Newcastle University, UK. His research interests include ice sheets, glacier geophysics, ice sheet hydrology and subglacial lakes, ice mass reconstruction, near-surface geophysics, pingos, and many other things. On the evidence of this blog, Neil has, through a seemingly random series of serendipitous events, apparently developed a nascent and unanticipated interest in ‘histo-glacio’ research. He (these days rather occasionally) tweets at @sledge_ross, very much hopes one day to recover his EU citizenship, and can be contacted at neil.ross@ncl.ac.uk.