They come in all shapes, sizes and textures. They can be white, deep blue or brownish. Sometimes they even have penguins on them. It is time to (briefly) introduce this element of the cryosphere that has not been given much attention in this blog yet: icebergs!

What is an iceberg?

Let’s start with the basics. An iceberg, which literally translates as “ice mountain”, is a bit of fresh ice that broke off a glacier, an ice shelf, or a larger iceberg, and that is now freely drifting in the ocean. As an approximation, you can consider that since an iceberg is already in the water (about 90% under water even), its melting does not contribute to sea-level rise. However, if you remember our Sea Level “For Dummies” post, you know that the melting of fresh ice reduces the ocean’s density and makes it expand. Icebergs are found at both poles, although they tend to be larger in the Southern Ocean. The largest iceberg ever spotted there was 335 by 97 km, which represents an area larger than Belgium !

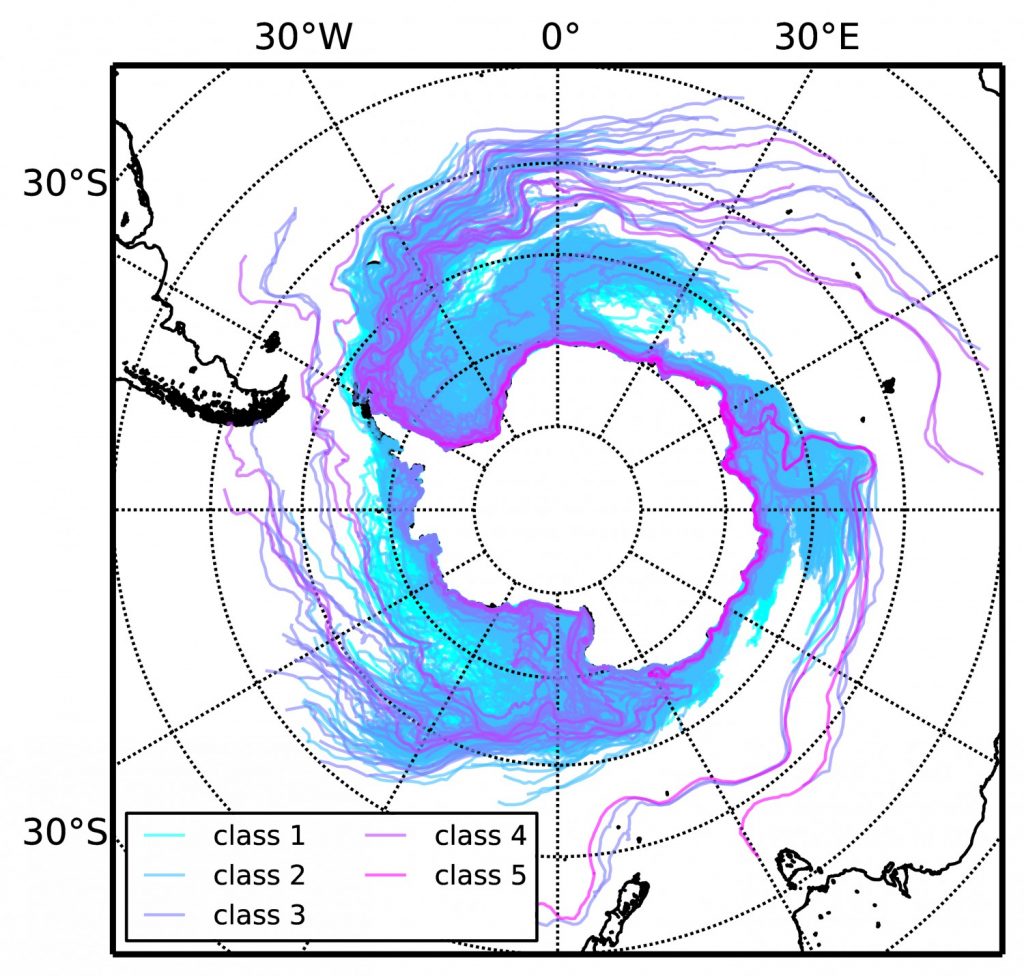

Modelled trajectories of icebergs around Antarctica. The different colours represent different size classes, ranging from 0-1 km² (class 1) to 100-1000 km² (class 5). [Credit: subset of Fig 2 from Rackow et al (2017)]

- The iceberg is eroded by the waves and melted by the relatively warm ocean;

- It can split in several pieces because of this melting and mechanical stress;

- Sea ice can freeze around it, trapping it in the pack ice.

This means that the iceberg changes shape a lot, and can be tricky to monitor (Mazur et al, 2017).

Why do we want to monitor icebergs?

You may have heard of the Titanic, and hence are aware that icebergs pose a risk for navigation not only in the polar regions but even in the North Atlantic. Icebergs also are large reservoirs of freshwater, and depending on how and where they melt, this inflow of melted freshwater can really affect the ocean; it even dominates the freshwater budget in some Greenland fjords (Enderlin et al., 2016).

Icebergs have traditionally been rather understudied, so we are only now discovering how important they are and how they interact with the rest of the climate system: increasing sea ice production (A. Mazur, PhD thesis, 2017), biological activity (Vernet et al., 2012), and even carbon storage (Smith et al., 2011). And sometimes, they have penguins on them!

All eyes in the CryoTeam are now turned to the Antarctic Peninsula, where a giant iceberg may detach from the Larsen C ice shelf soon. To learn how we know that, check this video made by ESA. And of course, continue reading us – we’ll be reporting about the birth of this monster berg!

Edited by Sophie Berger

Further reading

-

Enderlin et al. (2012), Iceberg meltwater fluxes dominate the freshwater budget in Greenland’s iceberg-congested glacial fjords, Geophysical Research Letters, doi:

-

Mazur et al. (2017), An object-based SAR image iceberg detection algorithm applied to the Amundsen Sea, Remote Sensing of Environment, doi:10.1016/j.rse.2016.11.013

- Rackow et al. (2017), A simulation of small to giant Antarctic iceberg evolution: Differential impact on climatology estimates, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, doi:

- Smith et al. (2011), Carbon export associated with free-drifting icebergs in the Southern Ocean, Deep Sea Research, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.11.027

- Vernet et al. (2012), Islands of Ice: Influence of Free-Drifting Antarctic Icebergs on Pelagic Marine Ecosystems, Oceanography, doi:10.5670/oceanog.2012.72