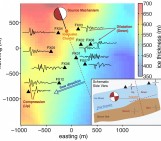

Figure 1: Simulation of a plume at a tidewater glacier in a general circulation model (MITgcm). Left – water temperature and right – time-averaged submarine melt rate in metres per day. Shown are face-on views of a tidewater glacier, as if you were under the water in front of the glacier, looking towards the calving front. 250 m3/s of fresh water emerges into the ocean from a channel at the bottom of the glacier, forming a plume. As the plume rises towards the fjord surface it mixes turbulently with warm ocean water, causing the plume to warm with height. Further details of this simulation can be found here: Slater et al. 2015.

Loss of ice from The Greenland Ice Sheet currently contributes approximately 1 mm/year to global sea level (Enderlin et al., 2014). The most rapidly changing and fastest flowing parts of the ice sheet are tidewater glaciers, which transport ice from the interior of the ice sheet directly into the ocean. In order to better predict how Greenland will contribute to future sea level we need to know more about what happens in these regions.

Tidewater glaciers meet the ocean at the calving front (Fig. 2), where ice undergoes melting by the ocean (“submarine melting”) and icebergs calve off into the sea. In recent decades, tidewater glaciers around Greenland have retreated (due to increased loss of ice at the calving front) and started flowing faster. This in turn causes more ice to be released into the ocean, contributing to sea level. Understanding the cause of these changes at tidewater glaciers is an ongoing topic of research.

![Figure 2: Kangiata Nunata Sermia, a large tidewater glacier in south-west Greenland. The expression of a plume originating at the base of the calving front is visible on the fjord surface as turbid sediment-rich water. [Credit: Peter Nienow]](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/10/fig2-1.jpg)

Figure 2: Kangiata Nunata Sermia, a large tidewater glacier in south-west Greenland. The expression of a plume originating at the base of the calving front is visible on the fjord surface as turbid sediment-rich water. [Credit: Peter Nienow]

One possible cause of change is an observed warming of the ocean around Greenland (Straneo and Heimbach, 2013). A warming of the ocean is likely to lead to increased submarine melt rates, which may in turn influence iceberg calving if, for example, melting results in instability of the ice at the calving front. Submarine melt rates are thought to be increased further by upwelling of warm water at the calving front (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

This upwelling water, called a plume, may be initiated by submarine melting of the ice, or by fresh glacial meltwater from the ice sheet surface. This fresh glacial meltwater penetrates to the base of the glacier and flows into the ocean from beneath the glacier, which may be hundreds of metres underwater. Once in the ocean, the meltwater rises buoyantly because of a density difference between the meltwater and ocean water, forming a plume. In order to better understand the effect of plumes on submarine melting, we can model plumes using a numerical model (e.g. MITgcm). Our image of the week (Fig. 1) shows such a model, which we can use to estimate submarine melt rates. In combination with simpler analytical approaches (Jenkins et al., 2011; Slater et al., 2016), we can estimate how submarine melt rates may change over time and from glacier to glacier (Carroll et al., 2016), and begin to assess the effect of submarine melting on tidewater glaciers and ultimately on future sea level rise.

Edited by Teresa Kyrke-Smith and Emma Smith

Donald Slater is a PhD student in the Glaciology and Cryosphere Research Group at the University of Edinburgh. His research focusses on understanding the effect of the ocean on the Greenland Ice Sheet. For more information look up his website or follow him on twitter @donald_glacier.

Pingback: Lovely @EGU_CR Image of the Week feature on glacial plumes and ocean melting by @donald_glacier of @EdinGlaciology https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/2016/10/28/image-of-the-week-plumes-of-water-melting-greenlands-tidewater-glaciers/ … - trumb

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Icebergs increase heat flux to glacier