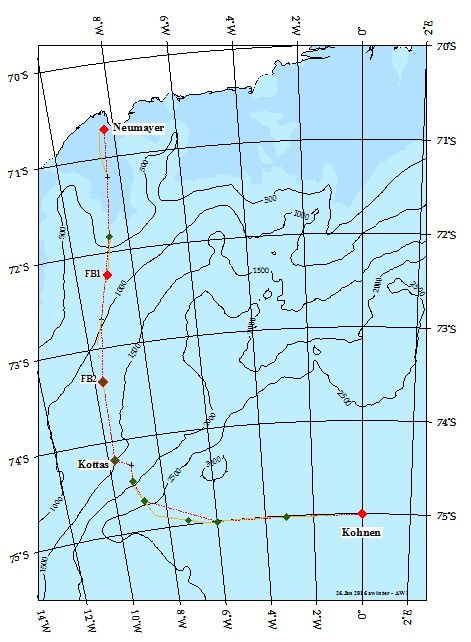

Working in the Arctic and Antarctic presents its own challenges. It is perhaps easy to imagine how a station situated close to the coast is resupplied: during the summer, one or more ships will arrive bringing fuel, food and equipment, but what about stations inland? Flying in supplies by aircraft is expensive and, in the case of large quantities of fuel, unsustainable. Besides, many stations are closed during the winter season, so there is nowhere for a plane to land until the skiway has been reestablished. The answer is of course that you drive. In other words, you go on a polar road trip, and one such road trip is the traverse that starts every year from the German Neumayer III station. The route is almost 800km long and it typically takes the traverse team 10 days to make their way across the East Antarctic Ice Sheet to their goal: Kohnen station at 75 degrees S, 0 degrees W and 2.9km altitude.

This year I got the chance to join the traverse and do a bit of science along the way with my colleague Anna Winter. Read below for a riveting tale of hardships, drilling and bamboo poles!

Who is holding up the traverse?

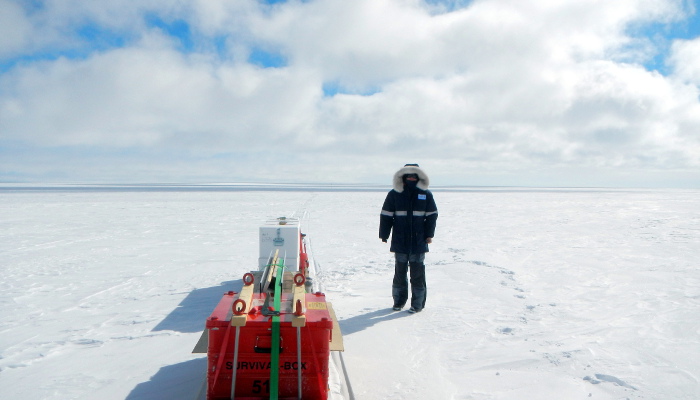

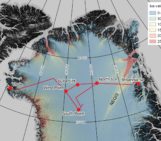

If you were to look at the traverse from above, you would see six large “Pisten bullies” pulling several sledges, each leaving a track across the ice sheet. However, you would also see two people on a tiny vehicle; a skidoo with two small sledges. Some times the skidoo will be in front of the traverse train, but often it will be trailing behind, and you would definitely notice that the people on the skidoo are stopping frequently. The two people are Anna and myself. We had set out to investigate how much snow is falling in this part of the Antarctic, and to do this we used a range of equipment from highly advanced radar instruments to bamboo sticks and a measurement tape.

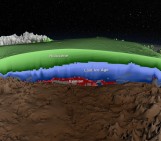

Drilling into the past

The Antarctic ice sheet has a long memory. When snow falls, the old snow is buried, so when you drill down into the surface you go back in time and can look into the past. This is how we know what the climate was like in the past. Drilling an ice core all the way to the bottom of Antarctica takes a very long time: often 3 – 5 years or more, but since we want to know something about the very recent changes, we do not have to drill very far.

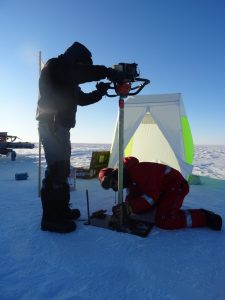

On the 31st of January the traverse stopped a bit earlier than usual, and while the drivers tended to the vehicles and the cook prepared the New Years Eve dinner, We started drilling a firn core (firn is old snow that is not ice yet) with the help of Alexander and Torsten. In order to drill a firn core, you need a drill that can capture the firn inside, a small engine for powering the drill and several extensions so you can go as deep as you like (see photo). It is not an easy process and many things can go wrong. For example, it should not be too warm when you drill. A few metres into the snow the temperature is no longer the same as the air, but instead it is the average annual temperature. Since we are drilling in the summer time this means that the firn we retrieve will be maybe 20 degrees colder than the temperature at the surface. When the drill comes up the metal gets warm and the core will get stuck inside the drill. A real nightmare! This is also the reason why we drilled during the evening even if that cut our New Years Eve celebrations short. Fortunately, we did manage to get a break and enjoyed a delicious New Years Eve meal, before finishing the drilling ten minutes before midnight. We celebrated the success of the drilling and the New Year with a whisky, before the cores were packed in boxes so they can be shipped to Germany for more analyses at the Alfred Wegener Institute.

Measuring a the height of a bamboo pole includes high-technology equipment, namely, another bamboo pole with peanut-can and a measurer tape stuck to it. Credit: Nanna B. Karlsson.

The endless row of bamboos

So, how do the bamboo poles fit in the picture? The firn core tells us a lot about the snowfall in the place where it was drilled, but we also want to know what is happening along the route of the traverse, and what is happening right now. Therefore, last year, bamboo poles were set up every 1km along the first part of the traverse. Our task was to increase the number of bamboo poles to one pole every 500m. We also measured the height of the old poles, and compared it to their original height. The further we got from the coast, the taller the bamboo poles were. This is what we expected since we know that very little snow falls in these parts of Antarctica, maybe less than half a metre a year! From our measurements, we now know directly how much snow has fallen since last year. Next year, other people will measure the height of the old bamboo poles and the new ones we put up, and we will know even more about the snowfall. It is a laborious and hard process: the traverse route is almost 800km so it is almost an endless row of bamboo poles. If only they could be seen from space they would make an impressive sight.

This blog post was originally brought on the website of the Alfred Wegener Institute in German. You can see more photos and read the originals here and here.

Tea break with Kottas Mountains in the background. For once we were ahead of the rest of the traverse. Credit: Anna Winter.

(Edited by Sophie Berger and Emma Smith)

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week — Where do people stay in the “coolest” place on earth?

Pingback: Afrique du Sud – un peu de chaleur avant le grand froid ! | Sophie en Antarctique