Today’s Image of the Week shows meltwaters originating from Leverett Glacier pouring over a waterfall in southwest Greenland. We have previously reported on how meItwater is of interest to Glaciologist (e.g. here) but today we are going to delve into how and why Biologists also study these meltwaters and how the cryosphere interacts with biogeochemical cycles in our oceans.

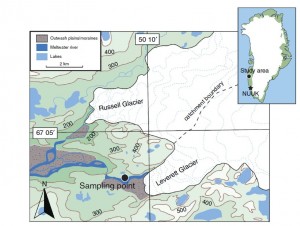

Figure 2: Location of Leverett Glacier. The glacier drains an area of 600 km2 of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Adapated from Hawkings et al. (2014) .

Where?

Leverett Glacier of the Greenland ice sheet (Fig. 2) discharges around 2 km3 of water a year from its 600 km2 catchment area. This single meltwater river has previously reached 800 m3 sec-1 at peak flow in the summer (in 2012; for contrast the Danube average flow is roughly 2000 m3 sec-1 as it passes through Budapest). These meltwaters are sediment rich and occur not just at Leverett but at hundreds of glaciers across the Greenland ice sheet, dumping a total of more than 400 billion tons of water in the oceans each year; a number than has risen steeply in recent years due to the rapidly warming Arctic climate. Relatively little is known about how this large seasonal input of glacial water may impact ocean life.

How?

Over the past few years fieldwork teams have visited Leverett Glacier each season to give us an insight into the importance of the Greenland ice sheet in supplying ecosystems with nutrients. To address this question they collect lots of water and sediment samples to analyse (using special instrument back in labs at The Universities of Bristol, Southampton and Leeds) and install semi-permanent sensors to see what’s happening to the river in real time (Fig 3).

These sensors record water temperature, depth, sediment concentrations and the amount of dissolved solids. This comprehensive dataset has provided a really nice picture of the system and the changes occurring at a high temporal resolution. They have also been testing cutting edge sensor technologies to measure things like nitrate and methane in the water more recently and, of course, they took some great drone footage of their work.

Figure 3: Semi-permanent sensor monitoring water temperature, depth, sediment concentrations and the amount of dissolved solids in glacial meltwaters from Leverett Glacier, Greenland (credit: Jon Hawkings).

What’s Happening?

These studies have found that glaciated regions, such as Greenland, are likely to be dumping large quantities of nutrients such as phosphorus, iron and silica into the polar oceans, feeding life at the bottom of the food chain and contributing to ecosystem health. This challenges the traditional view that ice sheets are relatively unimportant in biogeochemical cycles compared to other terrestrial environments.

Glaciers are like giant bulldozers crushing rock into finely ground rock dust as they move – it is this dust that give glacial meltwaters their milky colour. Water flowing below the ice, dissolves the minerals in the freshly crushed rock and transports them out into the oceans. These minerals provide nutrients that act as a fertilizer for ocean life – phytoplankton, the microscopic plants of the ocean, need rock derived nutrients to grow. These little guys are really important for the health of our planet. They form the base of the ocean food chain, and photosynthesise thus potentially capturing CO2 from the atmosphere. As glaciated regions like Greenland dump more meltwater into the oceans it is possible more nutrients could also be delivered, although more research needs to be conducted to ascertain if this is the case.

Want to find out more?

- Hawkings et al. (2014) Ice sheets as a significant source of highly reactive nanoparticulate iron to the oceans, Nature Communications, 5.

- Lawson et al. (2014) Greenland Ice Sheet exports labile organic carbon to the Arctic oceans, Biogeosciences, 11(14): 4015-4028.

- Hawkings et al. (2015) The effect of warming climate on nutrient and solute export from the Greenland Ice Sheet, Geochemical Perspectives Letters, 1: 94-104

- Hawkings et al. (2016) The Greenland Ice Sheet as a hotspot of phosphorus weathering and export in the Arctic, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 30: 191-210

Edited by Emma Smith

About Jon Hawkings:

Jon Hawkings is a post-doctoral research associate at the School of Geographical Sciences, in the University of Bristol. His research focuses on the biogeochemistry of the coldest areas of our planet. Specifically he is looking at the impact that melting ice sheets may be having on downstream and marine ecosystems. He enjoys working in some of the most inhospitable and challenging environments – pretty much all of his data stems from samples collected in the field. He tweets as @jonnyhawkings.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Canyons Under The Greenland Ice Sheet!