Extracted from a depth of 2,500 meters, a giant 12-meter long marine sediment core from the Fram Strait, between Svalbard and Greenland, preserves a climate record spanning up to 400,000 years. Its sediment layers offer crucial insights into the Arctic’s past, helping Dr Jochen Knies and his research team answer two important question: Was the Arctic ever ice-free during past warm periods? Will the Arctic be ice-free in the future?

Proxies: Unlocking climate history

In the lab, the core undergoes a series of detailed analyses to reconstruct its climate history, starting with the use of proxies —fingerprints left by the past—that allow scientists to infer past environmental conditions. Proxies help determine the age of each layer and uncover significant climate events, such as shifts in temperature, ice cover, and ocean dynamics.

For instance, the magnetic signature of an ancient rock in the sediments, reveal changes in Earth’s magnetic field, aiding in dating specific layers. Microfossils of marine organisms provide clues about past ocean temperatures and productivity. The abundance or scarcity of some oxygen isotopes provides further detail on historical water temperatures and ice volumes. By integrating these data, the team constructs a detailed timeline of Arctic climate changes spanning hundreds of thousands of years.

High-resolution sampling: Precision matters

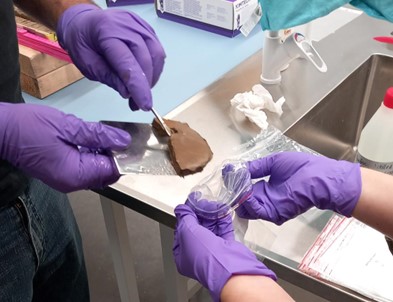

To maximize precision, the core is cut into 1-meter sections that are then sampled every centimeter, for further multi-proxy analyses. This high-resolution sampling captures intricate climate details from each layer. In some cases, core sections are sampled every half centimeter to detect even the most subtle climate shifts.

“We are particularly focused on warm climate periods like the last interglacial (~130,000 years ago) and the one before (~400,000 years ago),” explains Dr JochenKnies. “Examining these fine-scale samples allows us to gather a wealth of information about the Arctic’s climate during these critical times.”

Measuring water content

After analyzing proxies, the team measures the core’s water content. Sediment samples are weighed wet, dried, and reweighed to calculate water content, which reveals sediment density. This data helps determine sediment accumulation rates over time.

“Understanding how sediment accumulated during specific periods provides insight into past environmental conditions, including deposition rates of various materials,” noted Dr Jochen Knies.

Feeding climate models

Though this core reflects a single Arctic location, it forms a vital piece of a larger puzzle. “The data will feed into climate models, enhancing our understanding of the Arctic’s climate history and refining predictions for its future”, said Dr Jochen Knies.

Incorporating these findings into models helps scientists anticipate how the Arctic might respond to rising global temperatures. As one of the polar regions, the Arctic’s response to rising temperature is a key indicator of how other regions may respond in the future. Models results provide further guidance to our policymakers and and encourage them in their efforts to combat climate change.

Expanding the research

The current core is just the beginning. Next year, the i2B team plans another expedition on-board Norway’s ice-class research vessel, RV Kronprins Haakon, to collect additional geological archives from various locations in the Arctic Ocean. These new sediment cores will expand the dataset, offering a new piece to the puzzle and a more comprehensive picture of Arctic climate during past warm periods.

Led by Dr Jochen Knies, researchers within the newly funded European Research Council project, i2B – Into The Blue, aim to resolve past Arctic greenhouse climates and uncover valuable insights into how the region may evolve under ongoing climate change. This research is vital to understanding the complexities of global climate dynamics and enhancing predictive models for the Arctic’s future.

Dr Jochen Knies is also a research unit lead for the Norwegian Centre of Excellence, iC3: Centre for ice, Cryosphere, Carbon and Climate, which is based at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, and investigates how the links between ice sheets, carbon cycles and ocean ecosystems affect life on Earth.