Wildfires have been raging across the globe this summer. Six U.S. States, including California and Nevada, are currently battling fierce flames spurred on by high temperatures and dry conditions. Up to 10,000 people have been evacuated in Canada, where wildfires have swept through British Columbia. Closer to home, 700 tourists were rescued by boat from fires in Sicily, while last month, over 60 people lost their lives in one of the worst forest fires in Portugal’s history.

The impacts of this natural hazard are far reaching: destruction of pristine landscapes, costly infrastructure damage and threat to human life, to name but a few. Perhaps less talked about, but no less serious, are the negative effects exposure to wildfire smoke can have on human health.

Using social media posts which mention smoke, haze and air quality on Facebook, a team of researchers have assessed human exposure to smoke from wildfires during the summer of 2015 in the western US. The findings, published recently in the EGU’s open access journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, are particularly useful in areas where direct ground measurements of particulate matter (solid and liquid particles suspended in air, like ash, for example) aren’t available.

Particulate matter, or PM as it is also known, contributes significantly to air quality – or lack thereof, to be more precise. In the U.S, the Environment Protection Agency has set quality standards which limit the concentrations of pollutants in air; forcing industry to reduce harmful emissions.

However, controlling the concentrations of PM in air is much harder because it is often produced by natural means, such as wildfires and prescribed burns (as well as agricultural burns). A 2011 inventory found that up to 20% of PM emissions in the U.S. could be attributed to wildfires alone.

Research assumes that all PM (natural and man-made) affects human health equally. The question of how detrimental smoke from wildfires is to human health is, therefore, a difficult one to answer.

To shed some light on the problem, researchers first need to establish who has been exposed to smoke from natural fires. Usually, they rely on site (ground) measurements and satellite data, but these aren’t always reliable. For instance, site monitors are few and far between in the western US; while satellite data doesn’t provide surface-level concentrations on its own.

To overcome these challenges, the authors of the Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics paper, used Facebook data to determine population-level exposure.

Fires during the summer of 2015 in Canada, as well as Idaho, Washington and Oregon, caused poor air quality conditions in the U.S Midwest. The generated smoke plume was obvious in satellite images. The team used this period as a case study to test their idea.

Facebook was mined for posts which contained the words ‘smoke’,’smoky’, ‘smokey’, ‘haze’, ‘hazey’ or ‘air quality’. The results were then plotted onto a map. To ensure the study was balanced, multiple posts by a single person and those which referenced cigarette smoke or smoke not related to natural causes were filtered out. In addition, towns with small populations were weighted so that those with higher populations didn’t skew the results.

The social media results were then compared to smoke measurements acquired by more traditional means: ground station and satellite data.

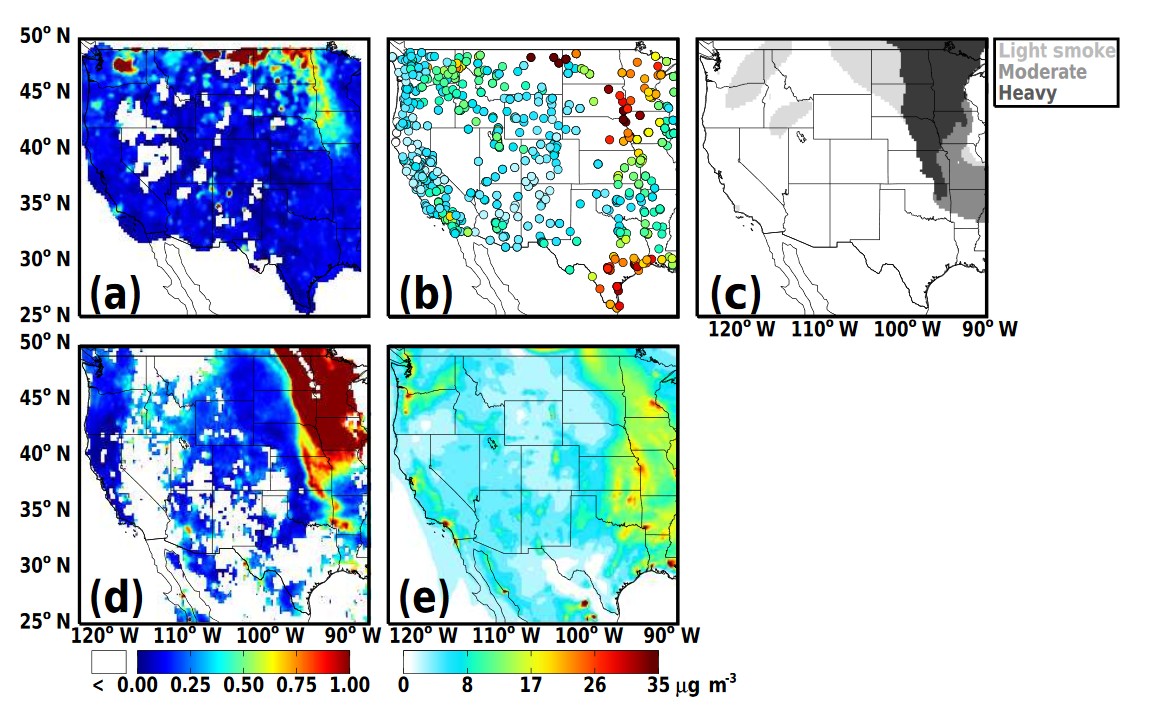

Example datasets from 29 June 2015. (a) Population – weighted, (b) average surface concentrations of particulate matter, (c) gridded HMS smoke product – satellite data, (d) gridded, unfiltered MODIS Aqua and MODIS Terra satellite data (white signifies no vaild observation), and (e) computer simulated average surface particulate matter. Image and caption (modified) from B.Ford et al., 2017.

The smoke plume ‘mapped out’ by the Facebook results correlates well with the plume observed by the satellites. The ‘Facebook plume’ doesn’t extend as far south (into Arkansas and Missouri) as the plume seen in the satellite image, but neither does the plume mapped out by the ground-level data.

Satellites will detect smoke plumes even when they have lifted off the surface and into the atmosphere. The absence of poor air quality measurements in the ground and Facebook data, likely indicates that the smoke plume had lifted by the time it reached Arkansas and Missouri.

The finding highlights, not only that the Facebook data can give meaningful information about the extend and location of smoke plume caused by wildfires, but that is has potential to more accurately reveal the air quality at the Earth’s surface than satellite data.

The relationship between the Facebook data and the amount of exposure to particular matter is complex and more difficult to establish. More research into how the two are linked will mean the researchers can quantify the health response associated with wildfire smoke. The findings will be useful for policy and decision-makers when it comes to limiting exposure in the future and have the added bonus of providing a cheap way to improve the predictions, without having to invest in expanding the ground monitor network.

By Laura Roberts, EGU Communications Officer

References

Ford, B., Burke, M., Lassman, W., Pfister, G., and Pierce, J. R.: Status update: is smoke on your mind? Using social media to assess smoke exposure, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 7541-7554, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-7541-2017, 2017.