Researching the Earth’s climate of the past, helps scientists make better predictions about how the climate and our environment will continue to be affected by, change and adapt to rising temperatures.

One of the most invaluable sources of data, when it comes to understanding the Earth’s past climate, are historical meteorological records.

Accounts of weather and climate conditions for the Southern Hemisphere, prior to the 1850s, are particularly sparse. This makes the recently discovered, painstakingly detailed and richly descriptive weather diaries of a 19th Century missionary in New Zealand, incredibly valuable.

Researchers from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, In Auckland (New Zealand), poured over the contents of the diaries, which provide an eyewitness account to the end of the Little Ice Age (between 1300 and the 1870s winter temperatures – particularly in the Norther Hemisphere- were lower than those experienced throughout the 20th Century). The journals reveal that 19th century New Zealand experienced cooler winter temperatures and more dominant southerly winds when compared to the present day climatic conditions. The researchers present these and other findings in the open access journal of the EGU, Climate of the Past.

Print of a photomechanical portrait of Reverend Richard Davis taken ca. 1860, from the file print collection, Box 16. Ref:

PAColl-7344-97, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, sourced from http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23073407 (From A. M. Lorrey et al., 2016).

The diaries were kept by Reverend Richard Davis, born in Dorset (England) in 1790. The Reverend was associated to the Church Mission Society (CMS) of England; an connection which lead him to settle in the blustery Northland Peninsula in the far north of New Zealand, back in 1831.

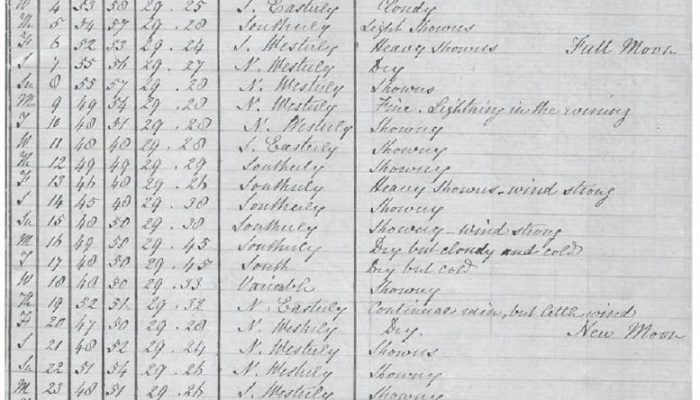

From 1839 to 1844, and then again from 1848 to 1851, Davis collected over 13,000 meteorological measurements and made detailed notes about the condition of the local environment.

The Reverend’s collection of data is remarkable, not only for its detail, but also because it is the earliest record of land-based meteorological measurements from New Zealand found to date.

He took twice daily temperature measurements – one at 9 a.m. and one at 12 noon – as well as noon pressure measurements. Qualitative observations included information about wind direction and strength, as well as detailed cloud cover descriptions, and notes on the occurrence of hail, frost, rainfall, snowfall, thunderstorms, lightning, sunsets and behavior of wildlife.

The journals also reveal that the Reverend was not keen on particularly gloomy days, when the winds were strong and blustery, cloud cover hung low and was often accompanied by rain. On 67 separate occasions, Davis’ used the term “dirty weather” to described days like this.

It is important to assess the reliability of the measurements taken by Davis before drawing comparisons between 19th and 20th Century weather patterns for the island of the long white cloud; and especially if the data are to be integrated within past climate and weather reconstructions for New Zealand and the Southern Hemisphere.

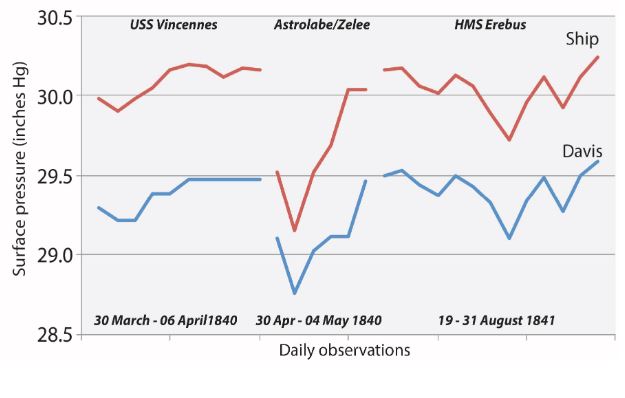

To do so, the Auckland based researchers, compared the Reverend’s pressure measurements with observations made by ships travelling through New Zealand waters or stationed on the island (usually completing military operations), during the same time interval. The Reverend’s daily pressure observations are regularly lower (on average by -0:64 ± 0:10 inches of mercury) than those taken on board the ships. The offset is consistent with the change in altitude between the ships anchored in harbour versus the land-based measurements made by Davis; meaning the Reverend’s pressure measurements are robust.

Reverend Richard Davis pressure observation vs. expedition measurements (leader noted in parentheses) from USS Vincennes (Wilkes), the corvettes Astrolabe and Zelee (d’Urville) and the HMS Erebus (Ross). There are 29 pairs of daily observations and so the x axis simply shows the comparisons of Davis’ record to the three ships in a sequence with the specific intervals noted. (From A. M. Lorrey et al., 2016).

There is no similar test which would verify the accuracy of Davis’ temperature measurements. However, the researchers argue that the (expected) annual cycles evident in his measurements, as well as the reliability of his other records mean that, at least some, of his readings are faithful to the local conditions. Not only that, Davis’ mean winter temperature anomalies are comparable to the temperatures reconstructed from tree rings and can be used by the researchers to gather information about the local atmospheric circulation at the time.

When compared to modern-day temperature measurements (from the Virtual Climate Station Network, VCSN), the journal data reveals that mid 1800s winters, at the far north of the island, were cooler. At present, atmospheric circulation over Northland means winds from the southwest are common, especially during the winter and spring. During the summer, easterly winds become dominant. There is a higher frequency of records of south and southwesterly winds in Davis’ diaries. Reconstructions of atmospheric flow over New Zealand in the 1800s, made with proxy tree-ring and coral data, also point towards more frequent south and southwesterly winds and cooler temperatures.

Not only that, the timing of monthly and seasonal climate anomalies, recorded both in tree-ring and the Davis diary data suggest that El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-like conditions existed, in New Zealand, during the 1839-1851 time period. However, more work (and data) is needed in Australasia to corroborate the findings and define the extent of the ENSO conditions at the time.

With more data, better reconstructions of the atmospheric conditions in the southwest Pacific and Southern Hemisphere can be made. Combined with the newly found Davis’ records, these will make an important impact to the understanding of past weather and climate in the region.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

The Waimate North mission house in the Far North of New Zealand where Davis lived (From: A. M. Lorrey et al., 2016).

References

Lorrey, A. M. and Chappell, P. R.: The “dirty weather” diaries of Reverend Richard Davis: insights about early colonial-era meteorology and climate variability for northern New Zealand, 1839–1851, Clim. Past, 12, 553-573, doi:10.5194/cp-12-553-2016, 2016.