Last week, a team of cryospheric scientists published a paper in The Cryosphere that showed how tiny plates of ice can lead to spurious estimates of sea ice thickness. This week, we’re featuring their findings, as well as some spectacular sea ice images in the latest in our Imaggeo on Mondays series…

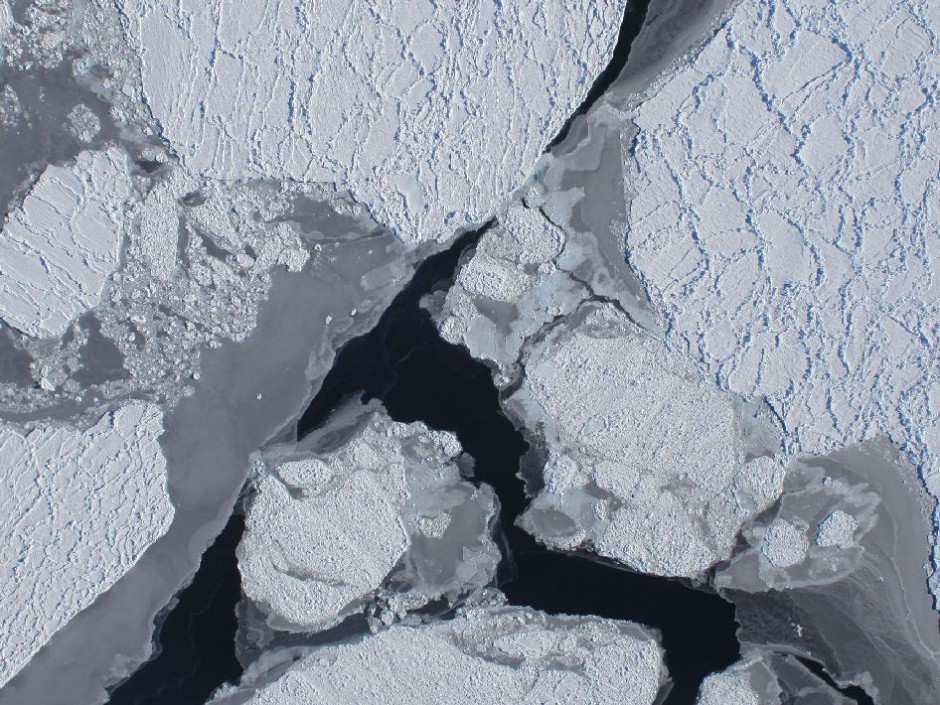

Viewing the poles from above is a stunning sight – a seemingly endless expanse of brilliant white, ridged blue crests, and delicate grey fringes that stretch like lace over the ocean. Such a vantage point also allows scientists to get to grips with what’s happening to these delegate fringes, seeing how far the sea ice stretches from year to year and how its thickness changes over time.

One of the best ways to measure how thick a large expanse of sea ice is, is to measure its elevation, comparing it to the level of the surrounding water to see just how much is floating on the ocean. This can be done swiftly using satellites, which have the added bonus of keeping a continuous record of change over time. But recent research reveals there may be a problem with this technique.

Spying on sea ice from some 20,000 feet above the surface. (Credit: NASA)

Beneath sea ice you find a fine crystalline mush composed of thin ice crystals, or platelets. These platelets bridge the boundary between sea ice and the sea below. Because ice is buoyant, this icy mush (aka the sub-ice platelet layer) pushes the sheet of sea ice upwards, increasing its elevation. Small differences in the proportion of platelets below the ice could make it appear thicker than it really is, leading to inaccurate measures of sea ice thickness.

Looking out over Antarctic sea ice. (Credit: Andrew Chiverton via imaggeo.egu.eu)

To know just how big a difference these platelets make, first you need to know how much solid ice is present in the mush. Using drill hole data collected in 2011, a team of scientists from New Zealand and Canada estimated that solid platelets made up about 16% of the mush beneath Antarctic sea ice. It may not sound much, but this many platelets could cause ice thickness to be overestimated by almost 20%.

You also need to know just how dense the platelets are. If they have a very low density, they can buoy the ice up more, and if they’re denser, they will have less of an affect on sea ice thickness. The findings mean a fair bit of ground-truthing will be needed to get better estimates of sea ice thickness from satellites in the future.

By Sara Mynott, EGU Communications Officer

Reference:

Price, D., Rack, W., Langhorne, P. J., Haas, C., Leonard, G., and Barnsdale, K.: The sub-ice platelet layer and its influence on freeboard to thickness conversion of Antarctic sea ice, The Cryosphere, 8, 1031-1039, 2014.

Imaggeo is the EGU’s open access geosciences image repository. Photos uploaded to Imaggeo can be used by scientists, the press and the public provided the original author is credited. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. You can submit your photos here.