Here, where the land ends and the sea begins...

Luís de Camões (Portuguese poet)

Lisbon. Spilled over the silver Tagus River, it is known by its beautiful low light, incredible food and friendly people. Here, cultures met, and poets dreamed, as navigators gathered to plan their journeys to old and new worlds. Fustigated by one of the greatest disasters the world has ever witnessed, Lisbon is intertwined with the course of Earth Sciences. For some, modern seismology was born here. For others, this might even have been the place where it all begun; what we now call geology.

On the morning of All Saints day of 1755, a giant earthquake struck the city of Lisbon. With a magnitude of ~8.7, the event was so powerful that it was felt simultaneously in Germany, as well as in the islands of Cape Verde. The main shock occurred around 9.40 am, when a significant portion of the population was attending the mass in churches. Lasting several minutes, many of the roofs collapsed and thousands of candles set fires that would last for days. While people were looking for safety at open areas near the river, three giant tsunami waves were on their way. Forty minutes after the main shock, the waves rose the Tagus River and flood the city’s downtown. The death toll in Lisbon reached up to 50,000 people, about one quarter of Lisbon’s population at the time. This event is known as the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

Painting depicting the day of the 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake. Credit: Wikipedia.

The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake was a terrific natural disaster. A few years ago, the French magazine L´Histoire, considered this earthquake as one of the 10 crucial events that changed history. At the time, Lisbon was a maritime power in a maritime epoch. This was also the age of Enlightenment, when man started to realize that many events such as earthquakes, volcanoes and storms, had natural causes, and were not sent by gods.

Convento do Carmo, destroyed during the 1755 earthquake and kept as a ruin for memory. Credit: Flickr.

Lisbon was in the spotlight of the modern world and some of the most prominent philosophers like Kant, Voltaire and Rousseau focused on the destructive event of the 1st of November, 1755. In particular, Emmanuel Kant published in 1756 (yes, 1756!) three essays about a new theory of earthquakes (see Duarte et al., 2016 and the reference list below for two of the Kant’s essays). I recommend all geoscientists to read these documents. It is incredible how Kant understands and describes how earthquakes align along linear features that are parallel to mountain chains. Does this sound familiar? Moreover, he uses the then new physics of Newton to calculate the forces that were needed to set the seafloor off Lisbon in movement in order to generate the observed tsunami. He even refers to experiments with buckets full of water to explain how the tsunami formed (analogue modelling!?). And Kant was not alone…

The minister of the King of Portugal at the time, the Marquis of Pombal, sent an enquiry to all parishes in the country with several questions. While some of the questions were intended to evaluate the extent of the damage, it is now clear that the Marquis was also trying to gain (scientific) knowledge about the event (see Duarte et al., 2016 and references therein). For example, he asks if the ground movement was stronger in one direction than in other, or if the tide rose or fell just before the tsunami waves arrived. Today, we can reconstruct with rigor what happened that day because of the incredible vision of this man.

The center of Lisbon today. The statue of Marquis of Pombal facing the reconstructed downtown. Credit: Wikipedia.

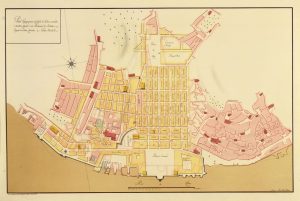

Coming back to Lisbon. If you visit the old city by foot, you will realize that houses on the hills are closely packed, separated by narrow streets and passages, while in the flat downtown streets are wide and orthogonal. The hilly parts of Lisbon are an heritage of the Moorish and Medieval times. Mouraria and Alfama are the ideal neighborhoods to visit. The organized downtown was the area that was totally floored during the earthquake, due to ground liquefaction and the impact of the tsunami, and was rebuilt using a modern architecture (see Terreiro do Paço and the downtown area in the first figure in the top). The Grand Liberty Avenue is clearly inspired by the style of the Champs-Élysées. Going up the Liberty Avenue, from the downtown, you will find the statue of the Marquis of Pombal (see figure above). And if you are already planning to visit (or revisit) Lisbon, you should definitely stop by the Carmo Archeological Museum, a ruin left to remind us all of what happened on that day of 1755, and the Lisbon Story Centre.

The hills of Lisbon, with the Castle in the top left and the 25 de Abril bridge in the background. Credit: Flickr.

Rebuilding plan after the 1755 earthquake. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

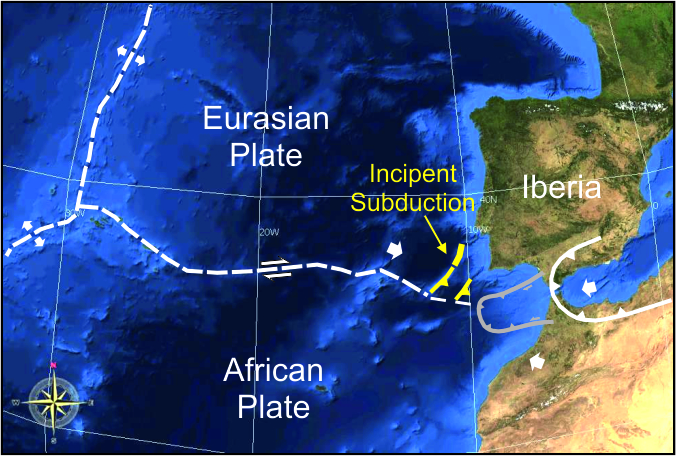

The 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake was however not the only earthquake that hit the city. On the 28th of February 1969, another major quake, with a magnitude of 7.9, struck 200 km off the cost of Portugal, at 2 am in the morning. The earthquake generated a small tsunami but luckily, given the late hours, did not caused any casualties. This event also occurred in a particular point in history: The time of plate tectonics. The paper that inaugurated plate tectonics had been published only 4 years before, by Tuzo Wilson. And in 1969, geoscientists already realized that some continental margins were passive and did not generate major earthquakes, such as the margins of the Atlantic, while others were active and fustigated by major earthquakes, such as the margin of the Pacific (Dewey, 1969). It was somewhat strange that this Atlantic region was producing such big earthquakes, which therefore immediately resulted in scientists coming to study this area (see map below).

Fukao (1973), studied the focal mechanism of the 1969 earthquake and concluded that it was a thrust event. Purdy (1975), suggested that this could result from a transient consumption of the lithosphere, and Mckenzie (1977) proposed that a new subduction zone was initiating here, along the east-west Africa-Eurasia plate boundary (see the thinner segment of the dashed white line in the eastern termination of the Africa-Eurasia plate boundary, map below), SW of Iberia. Later on, in 1986, António Ribeiro, professor at the University of Lisbon, suggested that instead, a new north-south subduction zone was forming along the west margin of Portugal (yellow lines in the map), a passive margin transforming into an active margin. This could explain the high magnitude seismicity, such as the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

Map showing the main tectonic features in the SW Iberia margin. The Eurasia-Africa plate boundary spans from the Azores-Tripe Junction (on the left) until the Gibraltar Arc (on the right, with its accretionary wedge marked in grey). The yellow lines mark a new thrust front that is forming and migrating northwards away from the plate boundary and along the west Iberia margin. The smaller yellow line marks the approximate location of the 1969 earthquake. The 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake might also have been generated in this region (see Duarte et al., 2013 for further reading on the tectonic setting of the region; the figure is adapted from this paper).

Today, we know that the SW Iberia margin is indeed being reactivated (Duarte et al., 2013). Whether this will lead to the nucleation of a new subduction zone is still a matter of debate, and we will probably never know for sure. Nevertheless, subduction initiation is one of the major unsolved problems in Earth Sciences, and the coasts off Lisbon might constitute a perfect natural laboratory to investigate this problem. It may be the only case where an Atlantic-type margin (actually located in the Atlantic) is just being reactivated, which is a fundamental step in the tectonic conceptual model that we know as the Wilson Cycle (see also Duarte et al., 2018 and this GeoTalk blog). In any case, we know that there are two other locations where subduction zones have developed in the Atlantic: in the Scotia Arc and in the Lesser Antilles Arc. How they originated is still being investigated; which is precisely what we are doing now in Lisbon. That is however a topic that deserves its own blog post.

Written by João Duarte

Researcher at Instituto Dom Luiz and Invited Professor at the Geology Department, Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon. Adjunct Researcher at Monash University.

Edited by Elenora van Rijsingen

PhD candidate at the Laboratory of Experimental Tectonics, Roma Tre University and Geosciences Montpellier. Editor for the EGU Tectonics & Structural geology blog

For more information about the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, check out these two video’s about the event: a reconstruction of the earthquake and a tsunami model animation.

References:

Dewey, J.F., 1969. Continental margin: A model for conversion of Atlantic type to Andean type. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 6, 189-197.

Duarte, J.C., Schellart, W.P., Rosas, F.R., 2018. The future of Earth’s oceans: consequences of subduction initiation in the Atlantic and implications for supercontinent formation. Geological Magazine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756816000716

Duarte, J.C., and Schellart, W.P., 2016. Introduction to Plate Boundaries and Natural Hazards. American Geophysical Union, Geophysical Monograph 219. (Duarte, J.C. and Schellart, W.P. eds., Plate Boudaries and Natural Hazards). DOI: 10.1002/9781119054146.ch1

Duarte, J.C., Rosas, F.M., Terrinha, P., Schellart, W.P., Boutelier, D., Gutscher, M.A., Ribeiro, A., 2013. Are subduction zones invading the Atlantic? Evidence from the SW Iberia margin. Geology 41, 839-842. https://doi.org/10.1130/G34100.1

Fukao, Y., 1973. Thrust faulting at a lithospheric plate boundary: The Portugal earthquake of 1969. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 18, 205–216. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(73)90058-7.

Kant, I., 1756a. On the causes of earthquakes on the occasion of the calamity that befell the western countries of Europe towards the end of last year. In, I. Kant, 2012. Natural Science (Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant Translated). Edited by David Eric Watkins. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Kant, I., 1756b. History and natural description of the most noteworthy occurrences of the earthquake that struck a large part of the Earth at the end of the year 1755. In, I. Kant, 2012. Natural Science (Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant Translated). Edited by David Eric Watkins. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

McKenzie, D.P., 1977. The initiation of trenches: A finite amplitude instability, in Talwani, M., and Pitman W.C., III, eds., Island Arcs, Deep Sea Trenches and Back-Arc Basins. Maurice Ewing Series, American Geophysical Union 1, 57–61.

Purdy, G.M., 1975. The eastern end of the Azores–Gibraltar plate boundary. Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 43, 973–1000. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1975.tb06206.x.

Ribeiro, A.R. and Cabral, J., 1986. The neotectonic regime of the west Iberia continental margin: transition from passive to active? Maleo 2, p38.

Wilson, J.T., 1965. A new class of faults and their bearing on continental drift. Nature 207, 343– 347