Women in Tectonics and Structural Geology by Lucia Perez-Diaz

On the day of Christmas Eve, five years before the turn of the century, Marguerite Thomas Williams (December 1895 – August 1991) was born. She was the youngest of her five siblings born to her parents Henry and Clara Thomas. We don’t know much about her early life. Perhaps her older brothers and sisters would take her by the hand when walking to school, maybe the family would go to the countryside around Washington D.C. where she grew up. At some point during her youth, her interest in the natural world was sparked. She was so fascinated by it that it would become the main subject of her life as a scientist and educator in geography and the social sciences (Johnson 2019).

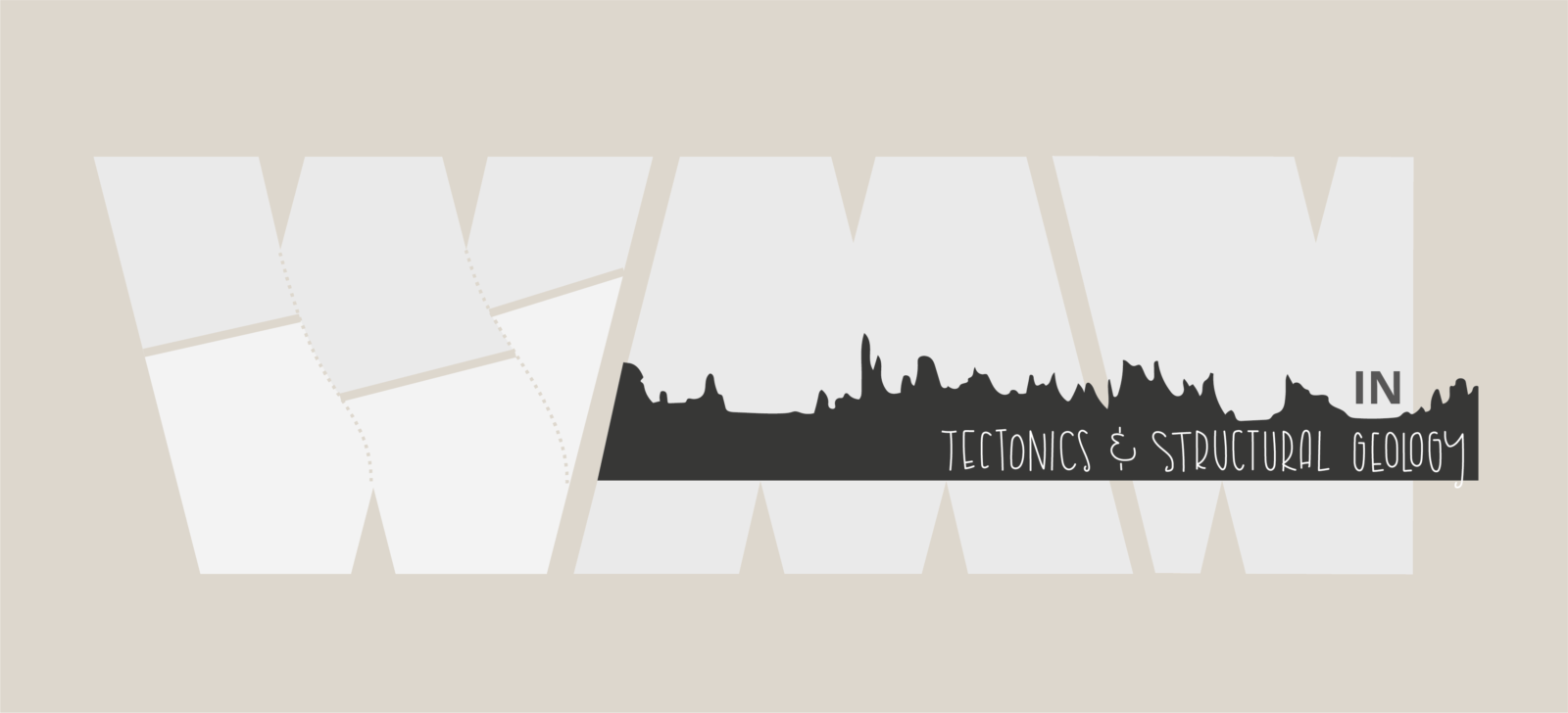

Marguerite followed the teacher-training program at what is now known as the University of the District of Columbia, known as the ‘Normal School for Colored Girls’ until 1879, after which it became the Miners Teachers College. She graduated in 1916 with high grades that allowed her to get a scholarship and continue her education at Howard University, Washington D.C. While she was teaching elementary school kids, she started a BSc program in Arts and Sciences and excelled in the natural sciences. During her studies, another promising black woman, Roger Arliner Young, majored in the natural sciences. Both women were mentored by eminent biologist Dr. Ernest Everett Just, (Johnson 2019) and even though Marguerite was more qualified than Roger, Ernest decided to give Roger a position as assistant professor at Howard University (Warren 1999), a massive achievement in a time when women predominantly taught English and Music at universities. The reasons for his decision are unclear, but nevertheless Ernest recognized Marguerite’s talents and interest for the natural world, her critical and scientific mind and he mentored Marguerite, motivating her to continue her studies. She successfully finished her degree in 1923.

Marguerite teaching to the students of Miner Teachers College. Courtesy of the District Univeristy of Columbia.

After Marguerite graduated from Howard University, she went back to Miner Teachers College where she was appointed the position of assistant professor and she occupied the ‘Chair of the Division of Geography’. She taught geography and worked with the school’s theatre group for a couple of years. During this time, she advocated for a more inclusive environment by unifying the different grades in kindergarten to increase community life (UDC digital archives 1951 – 2009). Even though she was very engaged with her work at Miner Teachers College, her thirst for knowledge to learn more about our planet was not stilled. She had been a bright student and she knew she could obtain a master’s degree. And so, it happened that after a few years of teaching she requested a study leave from Miner Teachers College to pursue a master’s degree in geology at Columbia University, from which she graduated in 1930.

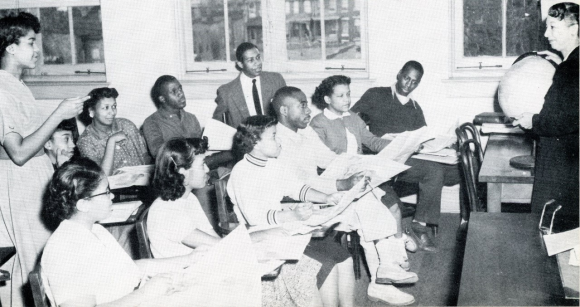

Map of the Land Utilization of the Anacostia River Basin, PhD Dissertation Marguerite Thomas Williams

After her graduation, she married Dr. Otis James Williams, from whom she adopted her last name. As a born educator, Marguerite immediately went back to Miners Teacher College to inspire more students about our planet Earth. However, she also had a passion for science and after a decade of teaching geography she decided to start a doctoral project at the Catholic University of America. Her work focused on the Anacostia drainage basin, located near Bladensburg in Maryland. Major floods occurred during the first half of the 20st century and affected the area greatly (McElrath 2014). This required a thorough investigation that Marguerite conducted diligently. She conducted fieldwork along the Anacostia River together with Dr. H.T. O’Neill. She complemented this work with a thorough literature review of books, bulletins and maps she received from different institutes, including the Geological Survey and the National Archives. She wrote an excellent PhD dissertation, in which she concluded that apart from natural erosional processes, human activity such as deforestation and agriculture, significantly contributed to the erosion observed in the Anacostia drainage system. She carried out her work effectively and defended her dissertation in 1942 (Williams 1942).

Cover page of Marguerite Thomas Williams’ doctoral thesis.

As soon as Marguerite received her Dr. title she was promoted to Full Professor at the Miners Teacher College. She also started to teach evening courses at Howard University. Until her retirement in 1955, she remained in her professorship position. Marguerite’s career was mostly dedicated to education of geography and social sciences, which is one of the reasons why her scientific work has been less visual. But even so, she remains one of the first geoscientists to recognise the influence of human activity and landscape management on erosional processes and natural flooding hazards.

Portrait of Marguerite Thomas Williams.

Marguerite Thomas Williams earning a doctorate, was a historical achievement. She was the first African-American person to obtain a doctorate degree in Geology in the United States of America. With that deed, she laid the first stepping stones for generations of African-American students to come today, Geosciences is still a white-people dominated field. In the USA, barely 10% of the doctoral degrees in Geosciences are awarded to people of colour (Dutt 2019; Bernard & Cooperdock 2018). Marguerite showed the world that it is possible to achieve the highest academic rank possible. In doing so, she became a role-model for people with a none-white background, mostly to women of colour. It is people like Marguerite that challenge the status quo and make Geosciences a more inclusive field of expertise.

References:

-

- “Marguerite Thomas Williams”, 2020. Trowelblazer, written by Nadia Johnson, https://trowelblazers.com/marguerite-thomas-williams/

- “Black women scientists in the United States”, 1999, Wini Warren. Indiana University Press, p. 298.

- “Chronology of the University of the District of Columbia and Its Predecessor Institutions”, 2019. University of the District of Columbia

- “The rise and fall of the Anacostia in Bladenburg”, Curated by Doug McElrath, University Libraries, University of Maryland, https://www.lib.umd.edu/bladensburg/river

- Williams, M. T., 1942, A history of erosion in the Anacostia drainage Basin, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C., 59p.

- Dutt, K., 2019. Race and racism in the geosciences. Nature Geoscience, 13, 2-3.

- Bernard, R.E., Cooperdock, E.H.G., 2018. No progress on diversity in 40 years. Nature Geoscience, 11m, 292-295.