Zürich, with its lake stretching towards the foot of the Swiss Alps in the South, is currently a charming city full of watersides, lively bars, students and bankers. In Switzerland, you’ll find a wide variety of landscapes and geological features over a relatively small area – from the Alpine mountain range in the South to the low-lying plateau and the Jura Mountains in the North. Located in close proximity to all these geologists’ playground areas, Zürich has been the home base of many pioneering researchers and geologists over the years. The city of Zürich itself is also closely linked with the course of Earth Sciences, as its topography and geomorphology have been shaped by glaciers during the last glacial maximum. Even in the busy streets of the city centre you can find hints of Zurich’s vast geological history.

The “rooftop of Europe”

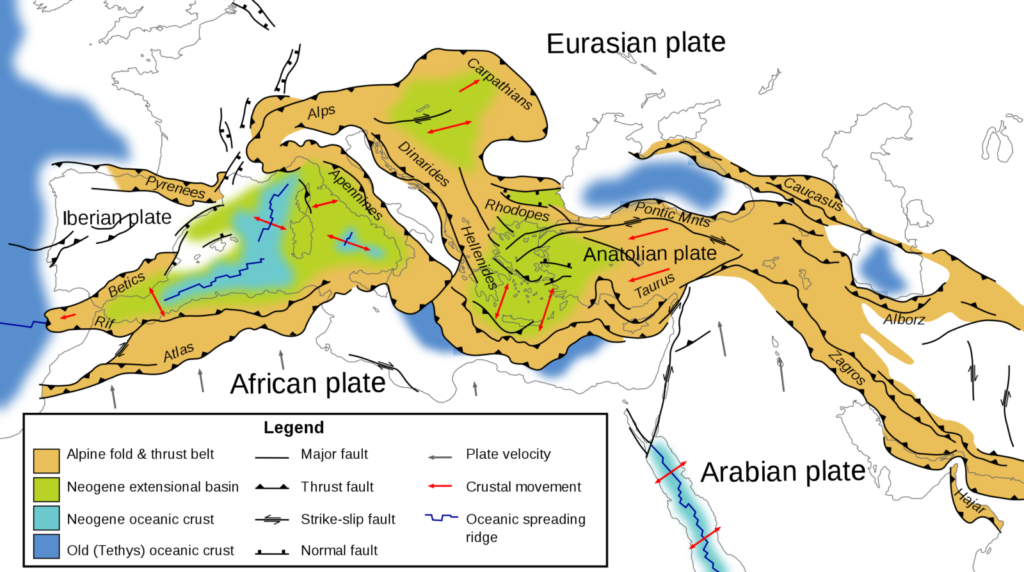

Zürich is with its ~400.000 inhabitants the most densely-populated city in Switzerland, and lies within the Northern foreland basin (“Molasse Basin”) of the Alpine mountain range. The Alpine mountain range is the result of a complex collision between the African and Eurasian plates, in which the Alpine Tethys oceanic crust, which was formerly between these continents, disappeared under the African plate. The northward-moving African continent scraped sediments of the Alpine Tethys basin into slices that were then pushed against the stable Eurasian continent. These slices folded into nappes that often slided over one-another to form gigantic thrust faults. To the north of the Alps, the Molasse basin developed, likely by flexural bending of the European plate in response to orogenic loading of the advancing Alpine wedge from the south. The name “molasse” stands for a sedimentary sequence of conglomerates and sandstones, material that was removed from the developing mountain chain by erosion and denudation, that is typical for foreland basins. The Alps were the first mountain system to be extensively studied by geologists, and many of the geologic terms associated with mountains and glaciers originated there. For example, the term Alps has been applied to mountain systems around the world that exhibit similar characteristics (such as the Southern Alps in New Zealand or the Lyngen Alps in Norway). Despite intensive studies, the complex geological history of the Alps remains one of the most heavily debated topics in solid Earth sciences.

Tectonic map of the Mediterranean, showing the position of the Alps within other structures of the western Alpide mountain belt (a chain of mountain ranges which extends along the southern margin of Eurasia). Credit: Woudloper, CC BY-SA 1.0. The Molasse foreland basin is located just north of the Alps.

Shaped by glaciers

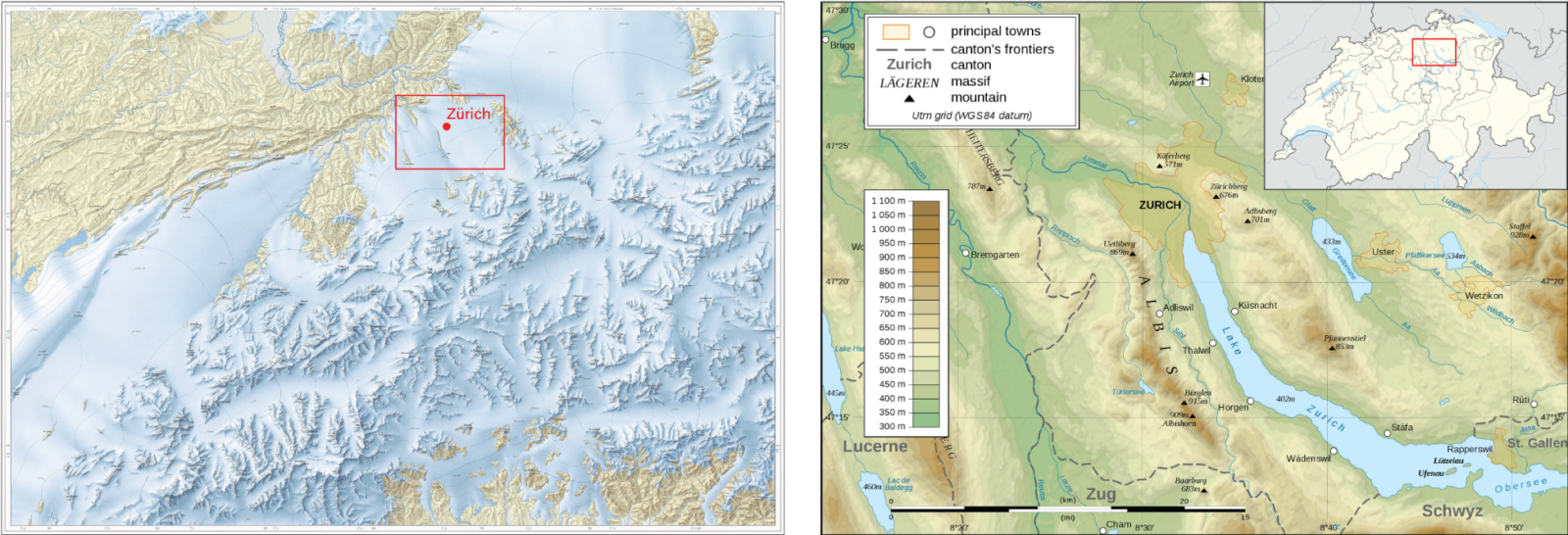

The last glacial period in the Earth’s history began around 115.000 years ago and extended up to 12.000 years ago. In Switzerland, this was an eventful time, as large parts of the country were covered by glaciers. To-date, traces of this ice age can still be found in the landscape features of Zürich and its surroundings. During this glacial period several pulses of advancing and retreating of glaciers from the Alps occurred (Seguinot et al., 2018). Check out this video on the advance and retreat of Alpine glaciers during the last glacial cycle. The powerful movement of the glacier ice carved out valleys in the underlying rocks and brought in rock debris – ranging in size from fine sediments to large boulders of several meters wide – across the landscape. This debris, deposited as so-called moraines, now forms the lush, green hills at the foot of the Alps. The deposited boulders, known as glacial erratics, can be found all across the country. The area of Zürich was particularly shaped by the Reihn-Linth-glacier, approximately 17.000 years ago. A 30-km long U-shaped valley extending from the Glarus Alps towards the Northwest was carved into Molasse bedrock by the Reihn-Linth-glacier, transforming into Lake Zürich as temperatures rose and the glacier retreated back towards the Alps. At the Northern-end of the lake, the low-lying land between the moraine hills and the lake would serve as the foundation for the settlement of the city Zürich.

Left: Switzerland during the last glacial maximum (LGM) 1:500.000. The map shows the maximum extent of glaciation in Switzerland at the height of the last Ice Age around 24,000 years ago. Credit: Bini et al., Swiss Federal Office of Topography. Right: Topographic map of Zürich and its surroundings. The hills surrounding the lake and city of Zürich (such as Zürichberg and Uetliberg) are in fact moraine walls once surrounding the Linth glacier around 20.000 years ago. Credit: Eric Gaba and NordNordWest, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The city of Zürich

Zurich has been continuously inhabited since Roman times. More precisely, the town’s origins date back to 15 BC, when the Romans established the town Turicum to oversee trade passing through the Alps. The core of the settlement was at the Lindenhof hill, where several Roman remains can be admired (such as Roman remains in the Lindenhofkeller or ancient Roman baths at the Thermengasse). In the centuries that followed, Germanic tribes took over the rule of the city, and as inhabitants weren’t very fluent in Latin, the town’s name gradually transformed into “Zürich”.

Left: view on the Lindenhof hill in Zürich, where the town was founded, and the Roman wall as seen from the river Limmat. Credit: Roland ZH, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0. Right: remains of Roman walls of the small Roman settlement Turicum, preserved in the Lindenhofkeller. Credit: Roland ZH, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Over the years, Zürich grew to be one of the major cities in Switzerland and is currently the financial centre of the country. Two major universities were founded in the city (Universität Zürich in 1833 and Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich in 1855), and today thousands of students crawl through the picturesque streets of Zürich, contributing to a lively vibe of the town. Moreover, the crystal-clear lake and the two rivers that run through the city centre enrich both the cityscape and the life of its inhabitants (if I may say so out of experience). Yet, due to its geographical location, Zürich can often be covered by a low-lying fog cloud in late autumn/early winter. This low-lying fog predominantly forms in high-pressure areas, which mostly occurs along rivers and lakes as air above these is very damp. Subsequent cooling of the damp air then causes local condensation. While this may lead to grey scenarios in the city, sunshine and superb views can be found at higher altitudes, sometimes even from the nearby hills. With the Alps within reach, the lovely waterfronts, hillsides as well as a scenic city, Zürich has much to offer for every type of travelling scientist.

Sketch of the main building of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zürich) overlooking the city in the 19th century. Credit: ETH Zürich.

References

Heim, A. 1878. Untersuchungen über den Mechanismus der Ge birgsbildung: Im Anschluss an die geologische Monographie der TödiWindgällenGruppe. Schwabe, Basel, 2 Bde. + Atlas, 346 und 246 pp.

Seguinot, J., Ivy-Ochs, S., Jouvet, G., Huss, M., Funk, M., and Preusser, F.: Modelling last glacial cycle ice dynamics in the Alps, The Cryosphere, 12, 3265–3285, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3265-2018, 2018.

Westermann, A; Trümpy, R (2008). Albert Heim (1849–1937): Weitblick und Verblendung in der alpentektonischen Forschung. Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich, 153(3-4):67-79.

Xin Xianwu

A beautiful city. I really want to see it.