Technically speaking, the Netherlands isn’t really a city, even though it is the most densely populated country in the European Union and one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with 488 people/km2. It is a delta, and for many people geology is not the first thing that springs to mind when thinking about the flat countryside. Large parts of the country have been more often below sea level than above.

The Netherlands, aka the flat country, seen from the air…

…and on the ground. Credit: Anne Pluymakers.

However, below the centuries of accumulated sand and clay, there are real rocks – rocks that form extensive reservoirs, for hydrocarbons (such as the Groningen reservoir, one of the world’s largest onshore gas reservoirs), potential CO2 storage reservoirs, as well as reservoirs now of interest to recover geothermal energy. It is the interest in these reservoirs that inspires many companies and the Dutch Geological Survey to figure out what lies below our feet. There is a publicly available database, the DINO database, which provides a view of the Dutch subsurface. It has been constructed using more than 135 3D seismic surveys and over 577.000 km of 2D seismic lines, as well as 1305 wells (www.dinoloket.nl).

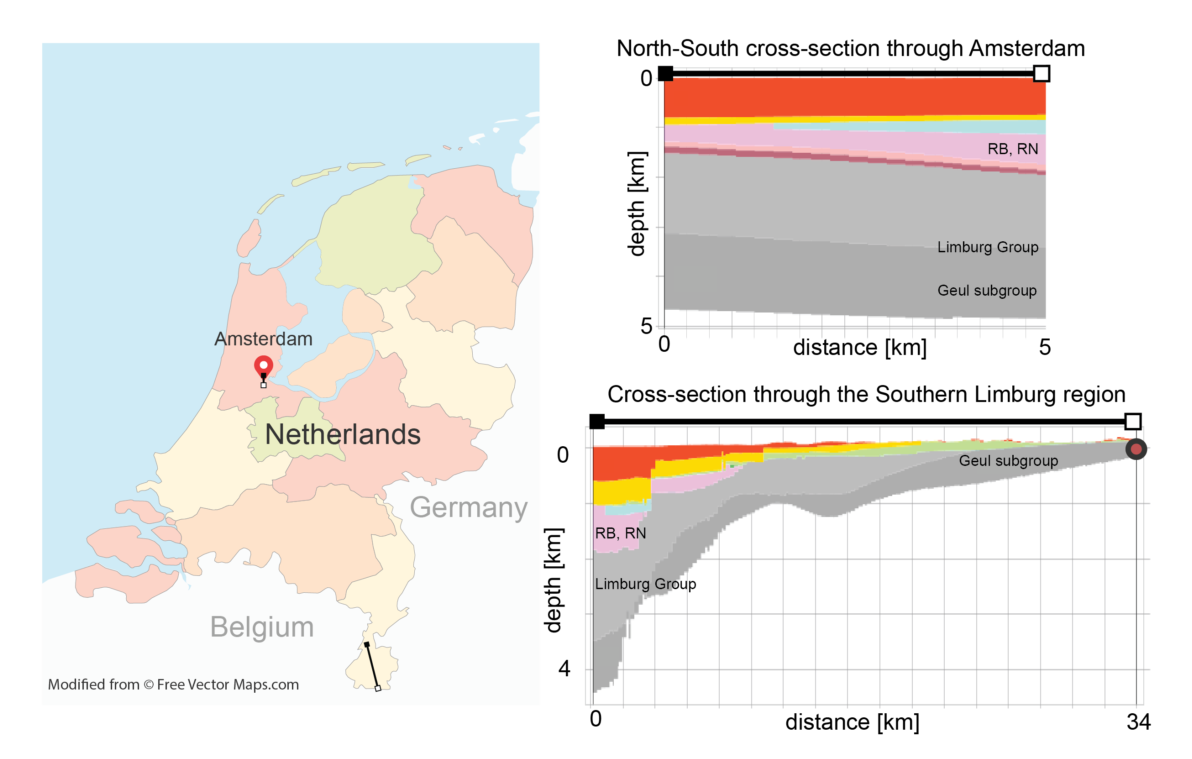

Left, a map of the Netherlands, with the approximate location and length of our cross sections indicated (Based on Netherlands with Provinces – Multicolor, by FreeVectorMaps.com). On the top right, a cross section through Amsterdam, with the formations as mentioned in the text. The same formations can be found in the south, but then at the surface. The Heimansgroeve, with the oldest outcropping rocks of the country, are part of the Geul subgroup, indicated with a red dot. (Cross sections from https://www.dinoloket.nl/ondergrondmodellen)

Everyone who visited the Netherlands will most likely remember the narrow merchant houses lining the many canals of Amsterdam. These houses are actually built on wooden piles, which are grounded in a sand layer at about 12 meters depth. Drawing a N-S profile through Amsterdam, we dig through many different deltas, swamps and bogs, showing thousands of years of rising and falling sea level. It is then no surprise that many of the mid-19th century houses are now tilted. Digging down in Amsterdam, it takes about 1000 meters until we find the first solid rock, the Upper and Lower Germanic Trias Group (RB, RN), consisting of clay-, sand- and siltstones. Below, there are relatively thin layers of the Zechstein and Rotliegend groups (red and pink), which contain the many on- and offshore hydrocarbon reservoirs found in Dutch territory. The lowest formation of interest (light and dark grey in the cross-sections above) is the Limburg group, in Amsterdam at 2 to 5 km depth. This is where we are heading! But instead of digging up Amsterdam, we travel south, to Limburg. This is the most southern province in the Netherlands, and as the map shows, it is wedged between the Belgian and German border. It is a region with a lot of tourism, and a great place to practice cycling uphill. This gently sloping countryside is the Dutch version of the Belgium Ardennes nearby, which are influenced by the Hercynian orogeny.

The Heimansgroeve was a quarry more than 100 years ago. Today, it is a geological monument. Credit: Anne Pluymakers.

The ancient castle of Valkenburg, a touristic town in Limburg. It was almost entirely built with the yellow marls from the region. Credit: Wikipedia.

The most famous rocks of Limburg are the yellow marls, remnants of a tropical sea and of Upper Cretaceous age. Even though they are soft, they have been used for centuries as building stones, where in the centre of the touristic little town of Valkenburg an ancient castle is almost completely made up out of marl. In the hills around this town hundreds of kilometres of tunnels have been excavated. When excavated 100 to 150 years ago, one cubic meter of marl used to cost 7 cents – though now a staggering €800,000 euro. Since the rocks are so soft, the only purpose for mining them nowadays is restoration.

It is in this region that we find the oldest outcropping rocks of the Netherlands. They surface in the Heimansgroeve, and are from the Geul Subgroup (dark grey in the cross section) and Carboniferous in age. The depositional setting of these rocks, consisting mainly of sandstones, coal layers and shales, ranged from deep basin, via prodelta, to delta front. Planning a visit to the outcrop with the oldest rocks of the Dutch mainland is surprisingly easy. From the parking lot of campsite Cottesserhoeve (paid parking) it is a leisurely walk towards the river Geul, and then a short walk along the river before we see the outcrop. This outcrop is part of the Heimansgroeve, a former quarry, northwest of Cottessen. In the early 20th century, this quarry was used to mine road-building material, and in 1910 it was discovered by the geologist Eli Heimans.

Fun fact: this region led to one of the first Dutch popular science books on geology, ‘Uit ons Krijtland’, published in 1911. It describes the countryside near this quarry, and encourages people to visit. In 1936, the Heimans quarry was enlarged by the geologist Willem Jongmans for research purposes. Nowadays it hosts a seismological station, to register the occasional earthquakes.

Tilted layers, slickensides and precipitation in open veins. All the features one would look for in the field are present, also in this outcrop in the flatlands! Credit: Anne Pluymakers.

Even though structurally it is not the most exciting place, it still shares many of the features a geologist looks for in the field. The quarry comes with a signpost explaining the geology, for any amateur- or potential future geologists passing by on a sunny day. Scurrying around, some other small details can be seen; all the features a wandering geologist is hoping for when out rock-hunting. Several places contain slickensides, an indicator for fault movement. For the mineralogist, there are plenty of tiny crystals to be found, showing fluid movement and precipitation in what must’ve been open fractures.

This outcrop shows you don’t have to dig that deep to witness real rocks in a country that is mainly known for being a Delta. So, next time you travel to the Netherlands, why not trade a touristy and overcrowded Amsterdam for a rock-hunting visit in the gentle sloping hills of the South?

Kate Pickering

Hi Anne, do you have any information about the geology of the Jekerkwartier district in Maastricht or the Maastricht area, or even South Limburg in general? I am trying to do some research for a project! Any info on this would be greatly appreciated! Thank you.

Anne Pluymakers

I am not an expert on Limburg geology, and mainly used Google scholar for my information. Not knowing if you are looking at the scientific level or the out-of-interest level, but the Dutch geological survey has some interesting things: https://www.geologischedienst.nl/geologie-voor-jou/geologische-wandel-en-fietsroutes/ This is in Dutch, but a translator should get you on the way.

Scientifically, you can have a look at the Netherlands Journal of Geosciences, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/netherlands-journal-of-geosciences This is one of your best chances for Dutch geology and local phenomena.