These blogposts present interviews with outstanding scientists that bloomed and shape the theory that revolutionised Earth Sciences — Plate Tectonics. Get to know them, learn from their experience, discover the pieces of advice they share and find out where the newest challenges lie!

Meeting Cesar Ranero

Prof. Cesar Ranero is an Earth Science researcher, currently Head of Barcelona Center for Subsurface Imaging (Barcelona-CSI). He owns a degree in Structural Geology and Petrology from the Basque country and he later completed his PhD in Barcelona, emerging himself in Geophysics. Prof. Ranero’s research is marked by a multidisciplinary approach, applying physical methodologies to understand geological processes.

Scientist also have to look for collaboration with the industry.

Ranero giving an outreach talk on fossil fuels at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB). Credit: Cesar Ranero

Hi Cesar, after doing research for few decades, what is, at present, your main research interest?

My research interest covers mainly active processes, I am not so interested in regional geology. I see regional geology as a necessary step to understand processes but the main goal of our group is to understand geological processes. For instance, a great interest in our group is the seismogenic zone and the generation of great earthquakes. We have very good examples in the Iberian peninsula, such as the famous 1755 Lisbon earthquake. Yet, nobody knows where the big fault that created this earthquake is located. We have a lot of research to do. But, often to understand local geology you need to integrate it in the big-picture view of processes. This is why we are mainly interested in those processes rather than in regional geology.

The more you know, the more you realize that nearly everything is to be discovered.

Further, I am interested in interacting with the industry. The geological/geophysical community is a relatively small community (compared to medicine, for example). There is out there quite a few industry groups that are doing very similar things in terms of methodologies and approaches (communities working in oil & gas exploration, or the ones working on carbon sequestration, or geothermal energy production…) All these communities have quite a bit of history in the development of methodologies. They usually have much more money and very talented people developing new methodologies. It is very necessary that we participate in their interests. They are often showing interest in what we do. By going to their meetings and talking to them, you can build fruitful interactions. Scientists also have to look for collaboration with the industry, because at the end of the day it is a place where some of our students can find a good job and make a career.

How would you describe your approach and methods?

The approach in our group is multidisciplinary, we combine complementary methodologies. But it is also important to be aware of proper methods to interpret geophysical data (you have to understand different geological methods, for instance, the methods used in structural geology).

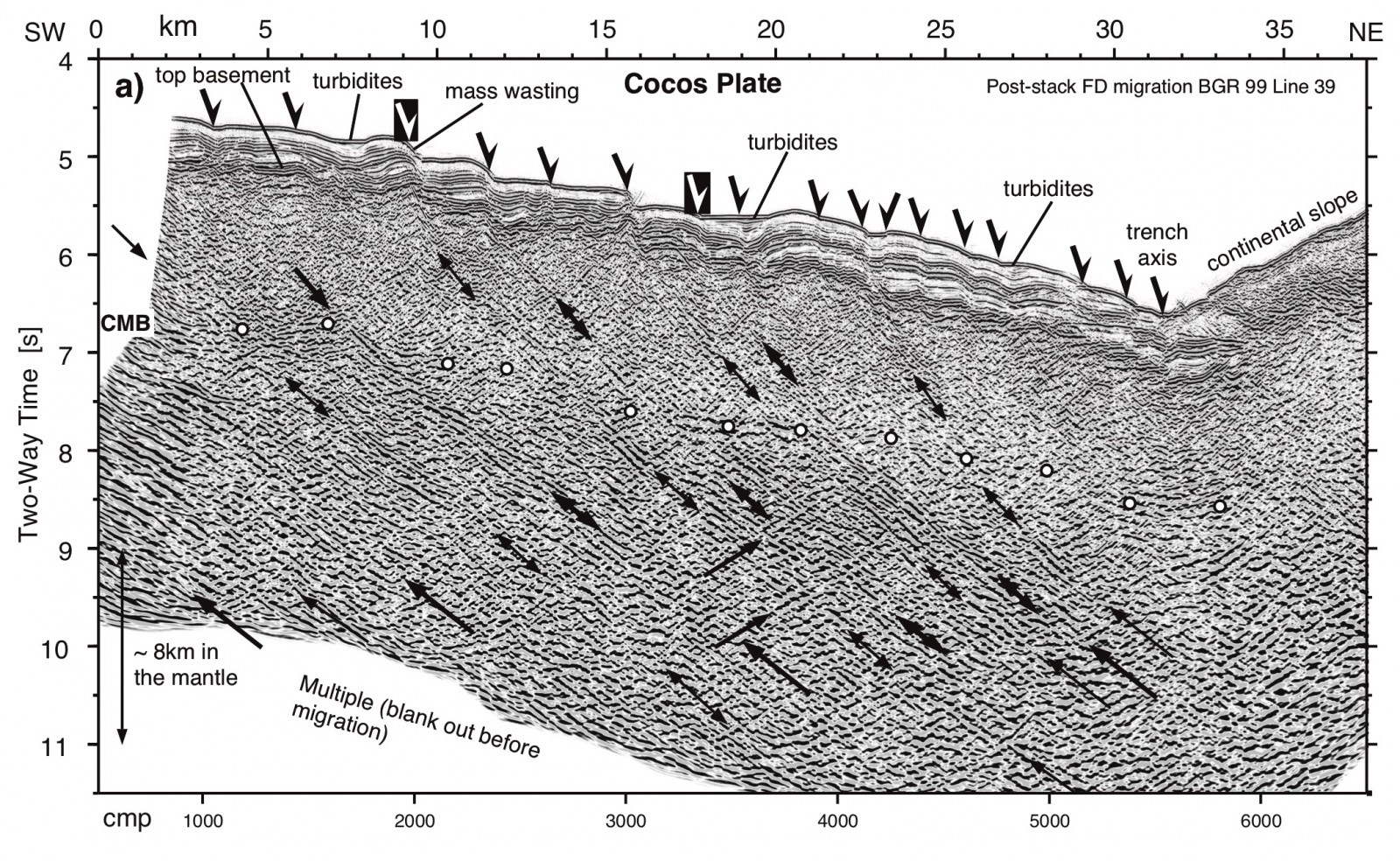

Poststack finite-difference time migration line showing the structure of the Cocos plate across the ocean trench slope. Ranero et al., 2003, Bending-related faulting and mantle serpentinization at the Middle America trench, Nature, 425, 6956, 367.

What would you say is your favorite aspect of your research?

What stroke me since I started my PhD is how much good work has been done, but how much more needs to be done.

We know a lot because there were many talented people before doing a lot of work. But actually, if you have a sceptical mind, the more you know, the more you realize that nearly everything is to be discovered. If you look at the last 10 years, you realize that a lot of what has been published is incremental science and much had been laid down in previous publications. But also, there are a whole series of new topics coming out and you have to pay attention because those are the topics that really mean a substantial jump forward. Every year there are several new interesting things coming. For example, earthquake phenomena have been an amazing topic in the last years, all these new phenomena explaining how plate boundaries slip. You have to keep a sceptical mind and at the same time search for those topics.

You have to have a sceptical mind.

Why is your research relevant, what are the real world applications?

This is always a good question. We do a lot of basic research and there is always the philosophical question on whether basic research is relevant… When we discovered the laser, nobody knew how relevant this would be in the future. Now, we can not live without it! I am sure that there is a percentage of basic science discovery that might not have any real-world application. But in many cases, it does. Much of what we do contributes to the understanding of natural hazards. But also, we contribute to resolving problems industries and society are concerned with.

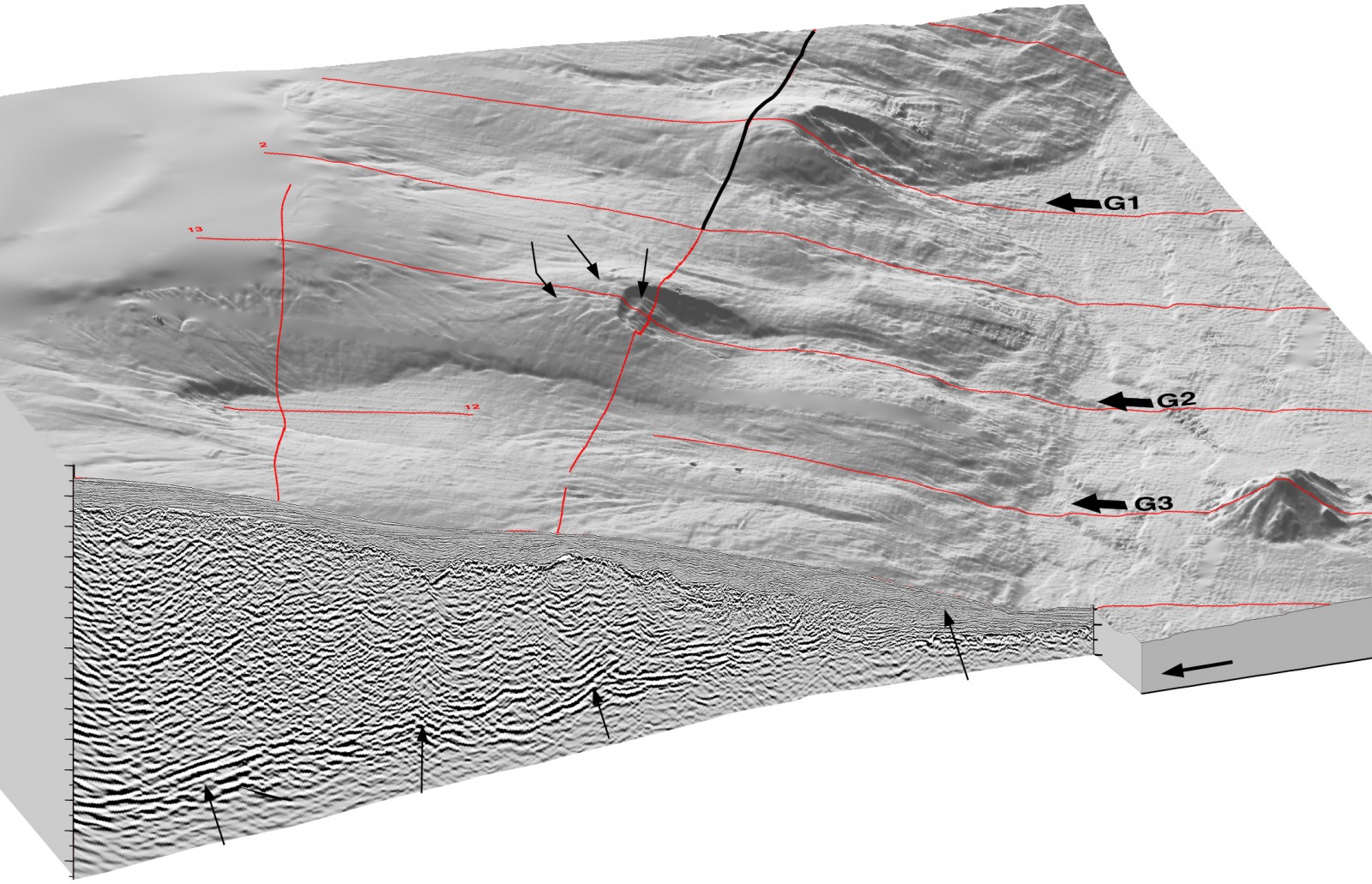

Prestack depth migration of a Sonne-81 line projected on bathymetry perspective. Ranero & von Huene, 2000, Subduction erosion along the Middle America convergent margin, Nature, 404, 6779, 748.

At this point of your career, what do you consider to be your biggest academic achievement?

I would like to think that it is the next one! (laughs)

I am proud to have been elected as a fellow of the American Geophysical Union. It means I have done something relevant that is appreciated by my peers, and at the same time, it is a great motivation to work even harder in the future.

Also, I have some nice papers that I am proud of (tectonics of subduction zones, the role of fluids on earthquakes, serpentinization of the outer rise). My view is that for most people, after you finish your career and you look back at your many publications, probably only 3-4 papers are really worth it and seriously contributed brand new material.

What would you say is the main problem that you solved during your most recent project?

Since I came back to Spain, 12 years ago, I started to work a lot in the Mediterranean. For many years, the Mediterranean had been a place where people did not want to work because it is too complex. With the help of German groups and others, our group has been able to characterize for the first time the nature of the crust in many systems in the Mediterranean. We have added a new layer of information to understand the evolution of the whole Mediterranean region. I am quite happy with that, we are producing quite a few papers and have some very new ideas, and we have also started to put that together with fieldwork. There has been a lot of on-land work all around the Mediterranean, but rather limited modern geophysical data on the nearby basins. For example, the Apennines are very well known, but the nearby Tyrrhenian, not so much… We worked with the Italian and the German groups and found some new, interesting geological observations.

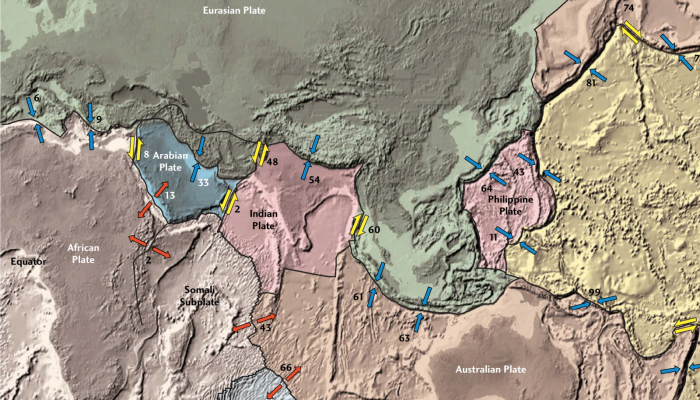

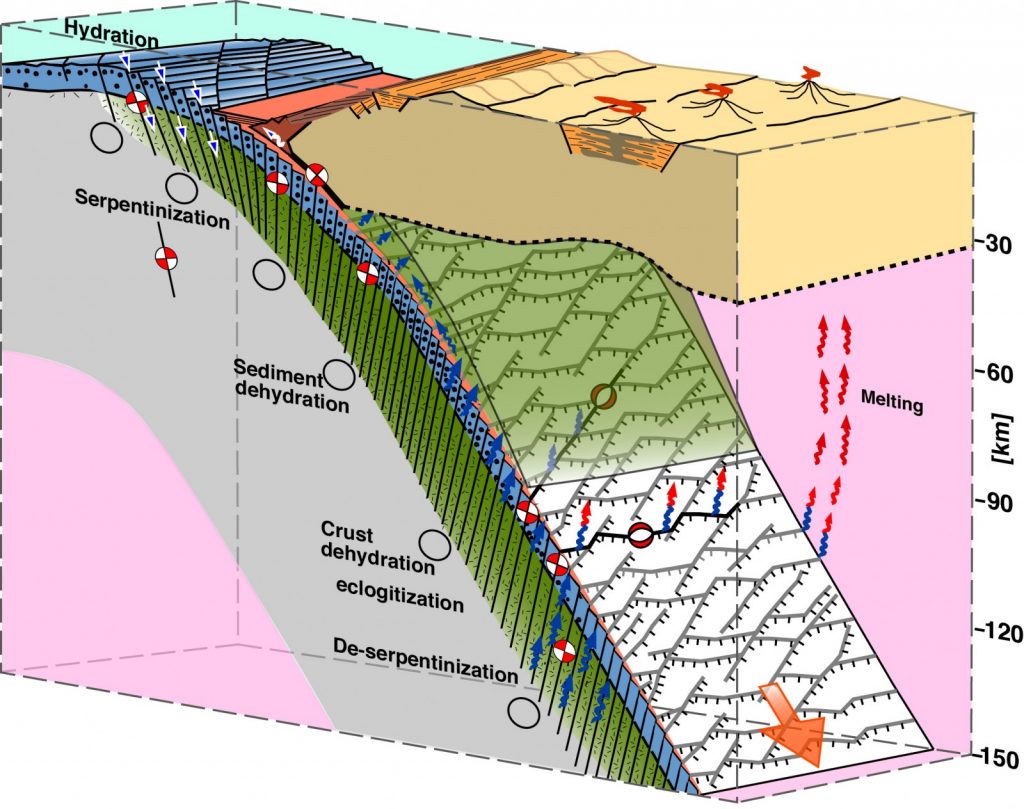

Cartoon showing a conceptual model of the structure and metamorphic evolution of subducting lithosphere formed at a fast spreading center. Ranero et al., 2005, Relationship between bend-faulting at trenches and intermediate-depth seismicity, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 6, Q12002, doi:10.1029/2005GC000997.

The biggest challenge is to have time to think about new observations of

high quality that challenges the conventional view

.

After being many years active in the academia, looking back, what would you change to improve how science in your field is done?

I think there are significant differences depending on the country, even within Europe, in terms of funding: how research is done, how research careers develop… Some countries, like Germany and France, are doing relatively good in terms of funding. Other countries, like Spain, Italy or Portugal are not. These countries do not have a well-organized structure for funding, so for researchers is difficult to know how to organize funding around their research to succeed. The people that do well, that work hard, that produce, should have the certainty that they will be able to move forward. But today there is a lot of uncertainty, and in these countries, there’s no warranty that people who deserve it, will have their chances. This is a major problem for ECR, and I think a better structure funding and more funding opportunities for ECR are needed.

Regarding European-funded projects, as for example those of the European Research Council, these programs are extremely prestigious, and only the very top are getting these very well funded grants. And yet, it is unclear to me, at least in my community, that the results and papers produced in the context of these programs are of higher quality than those in other funding programs. So, is it unclear to me that this is a system that we should sustain, but that we shall see in the next years. Talking to others, I get the perception that it is now becoming somewhat too prestigious, people even hesitate to submit proposals because they have to invest loads of time into it and is a huge effort that might not even pass the first evaluation, and review comments appear somewhat indecisive. But I might be wrong on this one.

What you just exposed, goes to some extent in line with my next question: What are the biggest challenges right now in your field?

As for the scientific challenges, I think we can look back at the Plate Tectonic revolution. How did it happen? Before it happened, many observations did not have a good explanation because we were lacking the right data. Then, almost suddenly, we got three datasets that nobody had seen before: magnetometers and echo sonars of higher quality coming from the second-world-war related research, and a worldwide seismological network for monitoring within the frame of the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty. And of course, these data landed on the right people. But, in my opinion, it was the access to the right data that provided a whole new view on geology.

So, perhaps the biggest challenge we have now is to be able to produce new methodologies of high resolution to look deeper into the Earth. We need to use high-quality new data sets and new observations that could allow to actually challenge the conventional views.

This is very complicated, particularly in the academic world we live in now. Currently, people have to write several papers for their PhD, and immediately after, in the postdoc period, they have to produce a massive number of papers to at least have a chance. In these circumstances, you can simply not think long enough in a complicated problem. There’s little time to think about what the main fundamental problems are that you want to solve. You have to be a paper-producing machine, and this is detrimental to their quality. You might manage to be someone that is highly productive but, in that frame, it is unlikely that you will often produce major quality. There’s too much pressure on ECRs. So, a challenge is to have time to think about how to obtain new observations of high quality that can change conventional views.

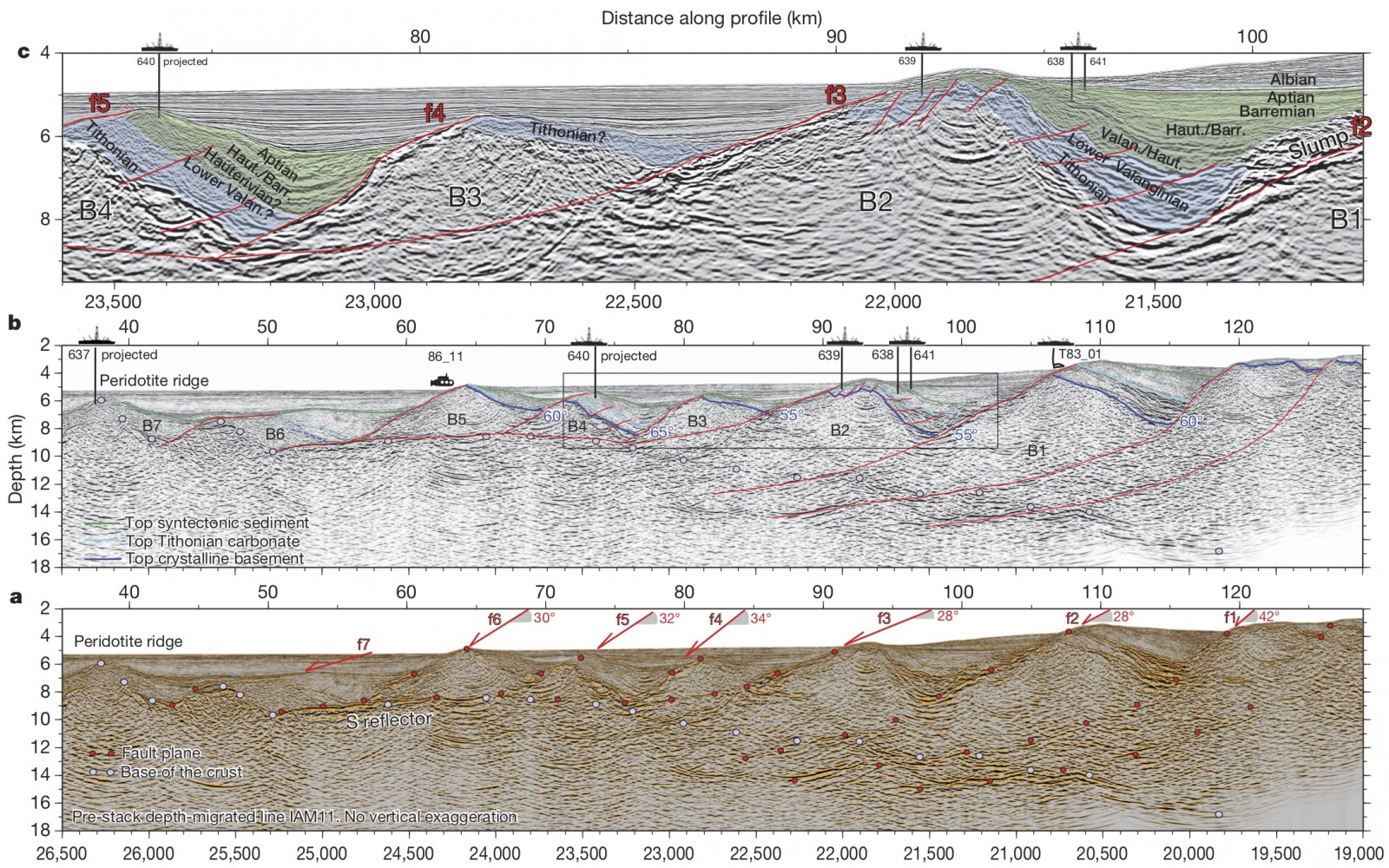

Pre-stack depth-migrated line IAM11, with arrows and numbers indicating the average dips of the block-bounding fault segments exhumed during rifting. Ranero & Pérez-Gussinyé, 2010, Sequential faulting explains the asymmetry and extension discrepancy of conjugate margins, Nature, 468, 7321, 294.

You have to be a paper-producing machine, and this is detrimental to their quality.

What were your motivating grounds, starting as an Early Career Researcher? Did you always saw yourself staying in academia?

I actually thought of going to the industry when I finished university. But I was lucky enough to be introduced to Enric Banda, my PhD supervisor, who had a big picture of geosciences, and he made a real impression on me and made me change my goals. Once I started my career in science, I quickly realized that there was a lot to be done. After two-three years into my PhD, thanks to a nice data set and some good results that were coming out, I definitely saw myself staying in academia. I looked for funding before finishing my PhD and I was lucky to get a Marie Curie, which was not even called like that at the time. I was lucky to work with relatively large groups, and with good funding. There was a good moment, also for industry. Funding was not a major issue for me for many years, so I could spend my time doing the research I wanted. At present, early careers are much more complicated, and you have to really like it to keep on pushing for it.

What advice would you like to give the ECS?

Be ambitious, think big. Don’t be afraid of making mistakes. And above all, be sceptical, completely sceptical about everything. Don’t pretend you know more about what you know, but be sceptical. Because, almost for sure, no matter who did the work, it can be improved, and in most cases, to a great extent. And be open, talk to everybody.

Researchers of the Barcelona Center for Subsurface Imaging. Credit: Cesar Ranero

Interview conducted by David Fernández-Blanco