Mind Your Head is a blog series dedicated towards addressing mental health in the academic environment and highlighting solutions relieving stress in daily academic life.

Besides the professional environment in general, the relationship between early career researchers and their advisors also plays an important role in the degree of stress researchers might experience. This relationship does not only depend on the type of advisor you have, but also on your own personality type. A tough supervisor for one person, might be a very good supervisor for someone else. The success of a healthy relationship therefore lies in the expectations you have for each other, and how you respond if those expectations are not met.

Different types of advisors

There are many different types of advisors, as there are many different types of people. A famous one is the ‘superbusy’ type, but also the ‘over-confident’ (“of course this never-tried method will work!”), or the ‘micro-manager’ (someone who checks every detail of your work), are common types.

The ideal advisor would be a supporting one, who cares about your future career, tries to teach you how to become an independent researcher and encourages you to do your work in a way that works best for you. The opposite would be someone who is interested in their own career and only sees you as someone who will simply take on some of their workload, whilst all the time keeping control on how you do that.

Generally speaking, advisors will fall in between these two extremes, and depending on their own stress levels, they might be easier to work with at some times than at others.

Expectations in both ways

The good news is that you can steer a little as well! So, how to make sure your situation will approach the ‘ideal’ situation, rather than the opposite? The first thing you need is probably a bit of luck; a good fit of characters might already be enough to obtain a healthy relationship.

If you’re not so lucky, then communication becomes key! Take the time to figure out what your advisor expects from you as an early career scientist and to think about what you expect from him or her. Advisors are all different, but students are too! Make sure to tell your advisor what you need in order to do a successful job. For example, does your advisor expect you to write your drafts mainly independent? Or does he or she prefer to work on it together, and check it after each section you’ve written? You both might have different preferences for this and it is important to discuss these and find a compromise.

If necessary, make an appointment once a year to simply discuss the process of decision-making and discuss what the best way of communication is for both of you. For example: some people prefer lengthy emails, some short, and some people you need to catch in person in order to work together. If you make it a habit to figure out what the best mode of communication is, it will definitely speed up any cooperation!

Most conflicts between PhD-students and supervisors arise in the final year of the PhD, since this is the point that the student thinks most independently. – Marie-Laure Parmentier (occasional consultant for Belpaeme Conseil)

When conflicts arise

When expectations are not met, a conflict may arise. An example is the case of the ‘superbusy’ advisor, who never has time to talk, whereas you would prefer to have regular short discussions (once in two weeks for example). This could lead to frustration on the students’ part, and even to giving up on trying to communicate at all.

A contrary situation could be an advisor who checks up on you daily to see how you are doing, probably with all the best intensions, whereas you prefer to work independently, and will only call your advisor when you are stuck. This situation could lead to the feeling of not working hard enough and not meeting expectations, which most likely is not the advisors intension.

Eventually these types of frustration will build up and slow down your work, so it is best to simply avoid it all together by discussing expectations clearly.

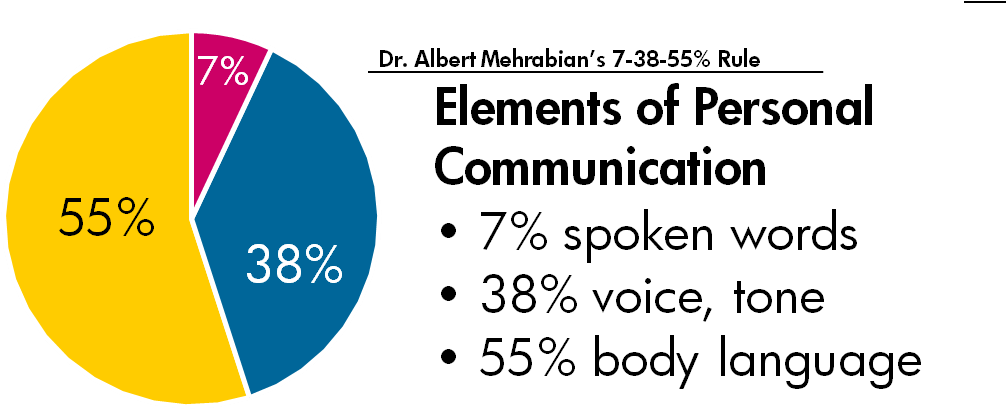

Albert Mehrabian’s 7-38-55 Rule of Personal Communication. Credit: www.rightattitudes.com

When a conflict arises, the most direct and understandable response is an emotional one; frustration, anger or quiet worry eating away at you. People often directly confront the person causing such an emotional response (which is very human!). However, as you probably know, this is not the smartest, nor the most professional way to deal with frustrations.

So, take a step back and calm down first, count to 10, briefly go to the gym, sleep on it, or go to a friendly colleague to shout out all your frustration; anything that works for you. Reflect on the situation, figure out what the main issue is, and then find a quiet moment during which you can discuss the problem in a calm and rational way. This will ensure your message is received and taken seriously.

In a direct conversation, the impact of your message is mainly determined by body language, while the contribution of the actual words is very little (only 7%). If your movements, space occupation, intonation and volume shout out your anger or your sadness, your conversation partner is likely to respond to the emotion, rather than the message, even if you manage to find the right words straight away.

To conclude: even when you have a different opinion than your advisor, when you are able to express your arguments carefully and clearly, it is much more likely that you’ll find a solution which works for both of you. Communication is key in becoming a better scientist, and will benefit you in any type of collaboration during your career!

By Elenora van Rijsingen

Written with help and revisions from Anne Pluymakers

Resources

2nd workshop of the Marie Skodowska-Curie ITN project CREEP: Discussion sessions between senior- and early career scientists focused on reducing stress levels in academia.

PhD management training by Marie-Laure Parmentier from Belpaeme Conseil, France.

nganga

True, the final year brings most conflicts