I’m Himanshu Kaushik, a PhD student working under the guidance of Dr. Mohd Farooq Azam at the Indian Institute of Technology Indore (India). Seven years ago, I took my first steps onto the Chhota Shigri Glacier (CSG) in the Indian (Western) Himalaya, and it felt like stepping into another world. Surrounded by the towering peaks, it seemed otherworldly and humbling. After that first expedition, I have visited this glacier about 16 times, each trip uncovering new insights and deepening my connection with this white icy wonderland. Before visiting, I had read about many glacial features in textbooks, but after stepping onto the CSG, it was as if these textbooks had come alive. This glacier was a perfect natural classroom, showcasing the incredible diversity of glacier features in one place. In this post, I’ll share my journey to the CSG, a perfect confluence of science and adventure (other records of field reports can be found here or here). This glacier has taught me about the changing climate and the resilience and fragility of nature and the human spirit. We’ll explore how this glacier reveals the impacts of climate change, and I’ll share stories from my field expeditions and working in such an extreme environment.

Chhota Shigri: A glacial sentinel of the Himalaya

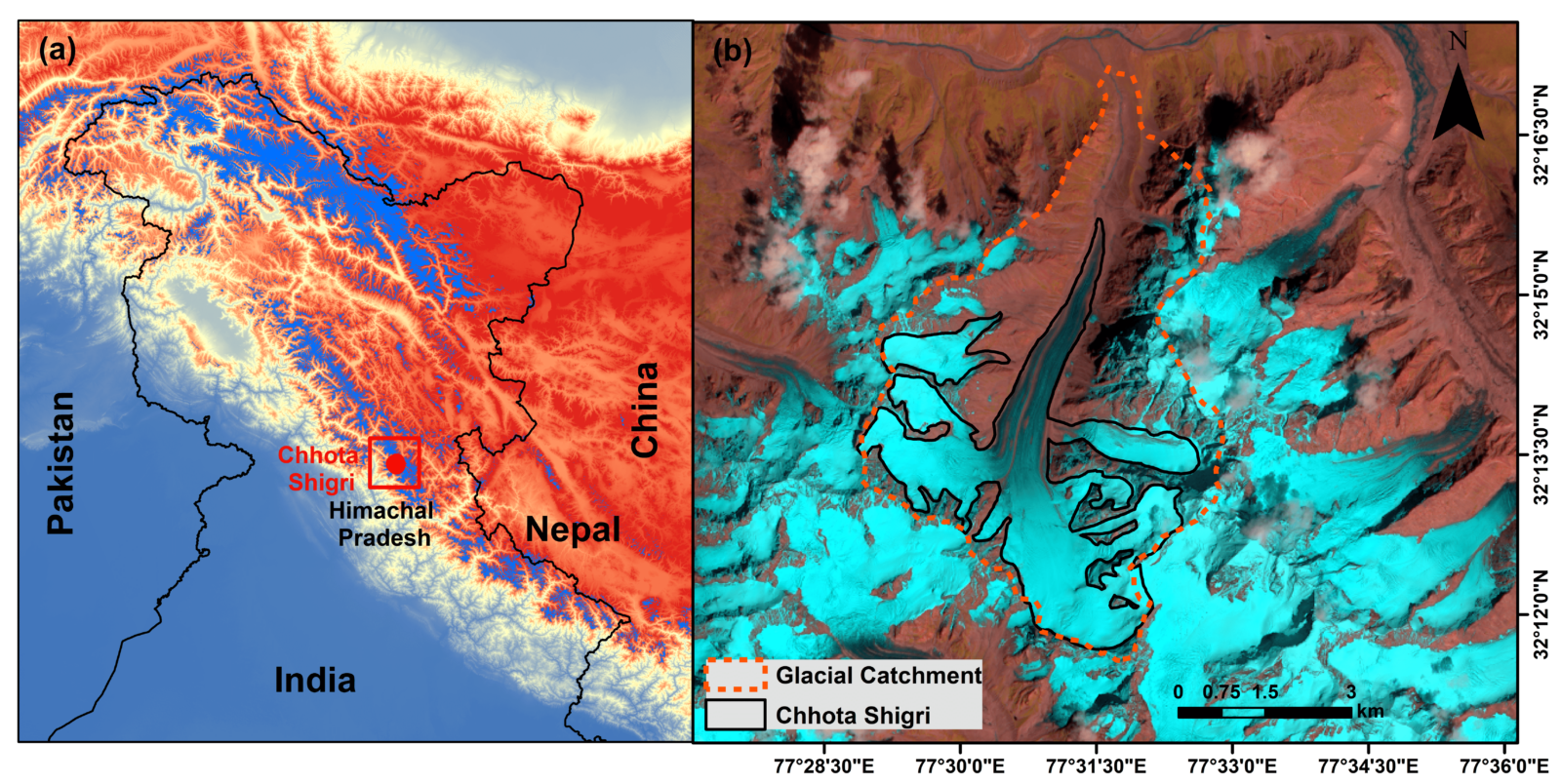

Why are we particularly interested in the CSG and endure the harsh conditions of trekking to it multiple times a year? The answer lies in its role as a benchmark glacier, offering vital insights into Himalayan glaciers. India began monitoring the CSG from 1987 to 1989 and again from 2002 onwards, making it the longest-monitored glacier in the Himalaya. Thus, continuous monitoring enables the use of field data obtained from CSG as a baseline for numerous modeling and remote sensing studies. CSG is a valley-type glacier in the Western Himalaya, located in Himachal Pradesh, a state in northern India (Figure 2). It covers about 15.5 km² and feeds the Chandra River, a tributary of the Chenab River (Indus River System).

Figure 2: Map showing an overview of the Himalaya and Himachal Pradesh (a), with an inset view of the CSG (b) (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik).

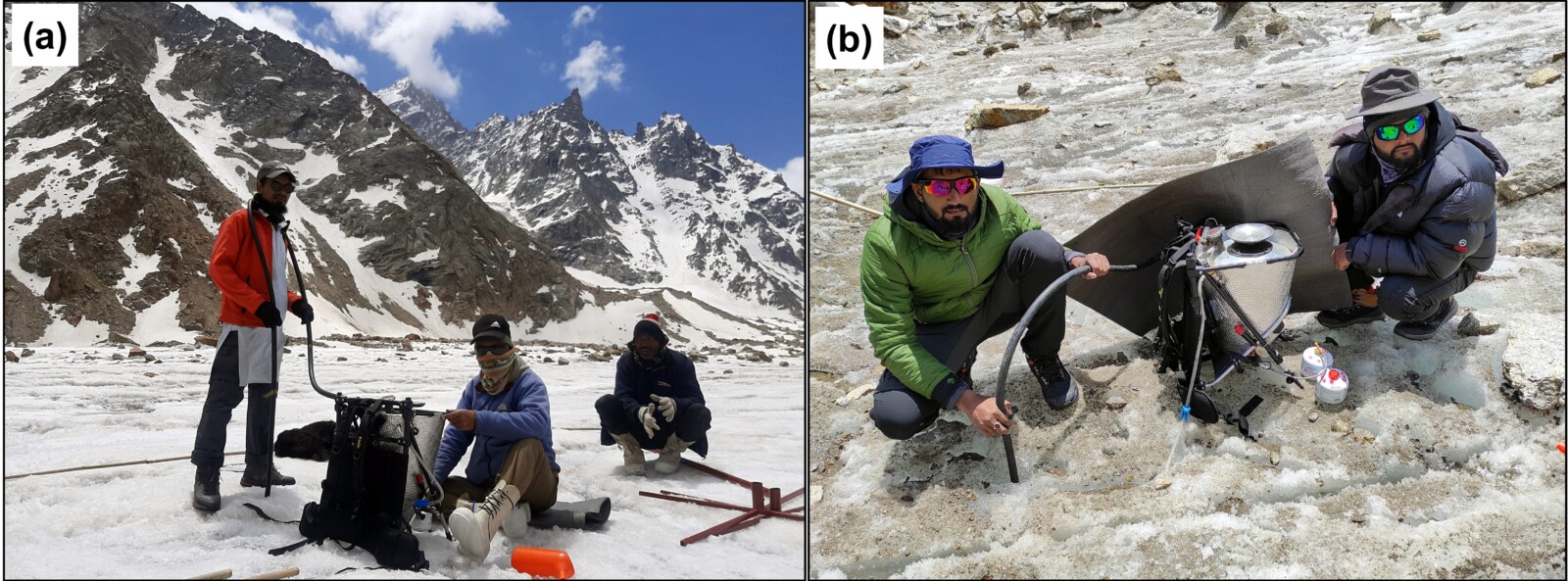

Our primary focus is determining the glacier’s mass balance – the difference between ice gained through snowfall (accumulation) and ice loss due to melting and sublimation (ablation). This measurement is critical for understanding the glacier’s health. We installed stakes to measure ablation. These stakes, driven deep into the ice using steam drills, serve as reference points for measuring ice melt over time (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Stake installation between 4200 and 4900 m a.s.l at CSG (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik (a) and Sachin Kumar Thakur (b)).

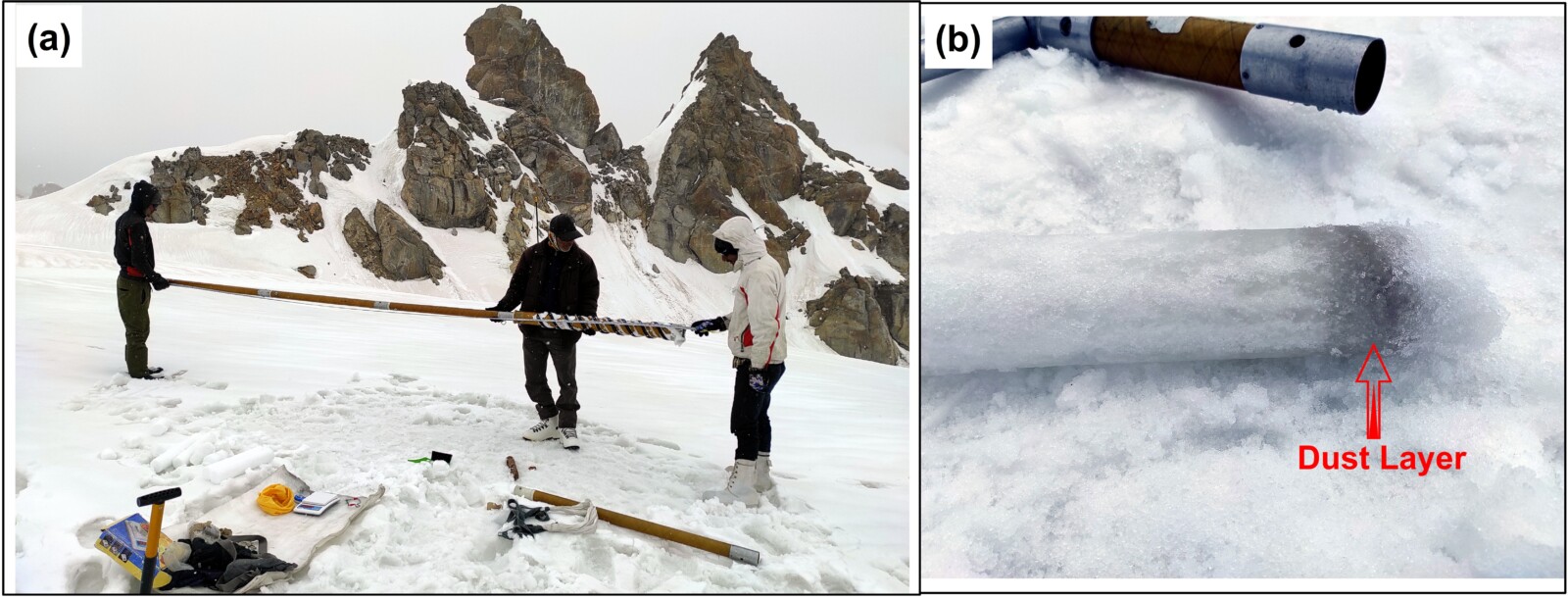

Once ablation measurements are completed, we focus on the accumulation zones higher up the glacier (Figure 4). Reaching these areas is no small feat. The eastern and western accumulation zones above 5,200 m a.s.l are accessible only after crossing treacherous crevasse fields and steep inclines.

We collect snow core data in the accumulation zones to measure snow density. Our main task in snow coring is identifying the dust layer, which provides insights into how much snow has accumulated over the past year. Identifying it is crucial for accurately measuring annual snow accumulation and mass balance.

Figure 4: Accumulation zone at 5300 m a.s.l., with snow core measurements (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik).

To understand the glacier, we installed a network of monitoring instruments, including automatic weather stations (AWS), a precipitation gauge, and a discharge station (Figure 5). Ensuring the proper working of this network of instruments requires us to undertake two or three expeditions each year during the summer.

The data we collect is vital for understanding the CSG and broader trends in Himalayan glaciers, and their findings consistently point to a worrisome reality: rising temperatures accelerate glacier melt, increase the risk of glacial hazards such as glacial lake outburst floods or ice avalanches and ultimately affect freshwater availability.

Figure 5: Instruments at the CSG: precipitation gauge at base camp (a), high camp (b) and the discharge site (c) (Credit: Arif Hussain (a & b); Mohd Farooq Azam (c)).

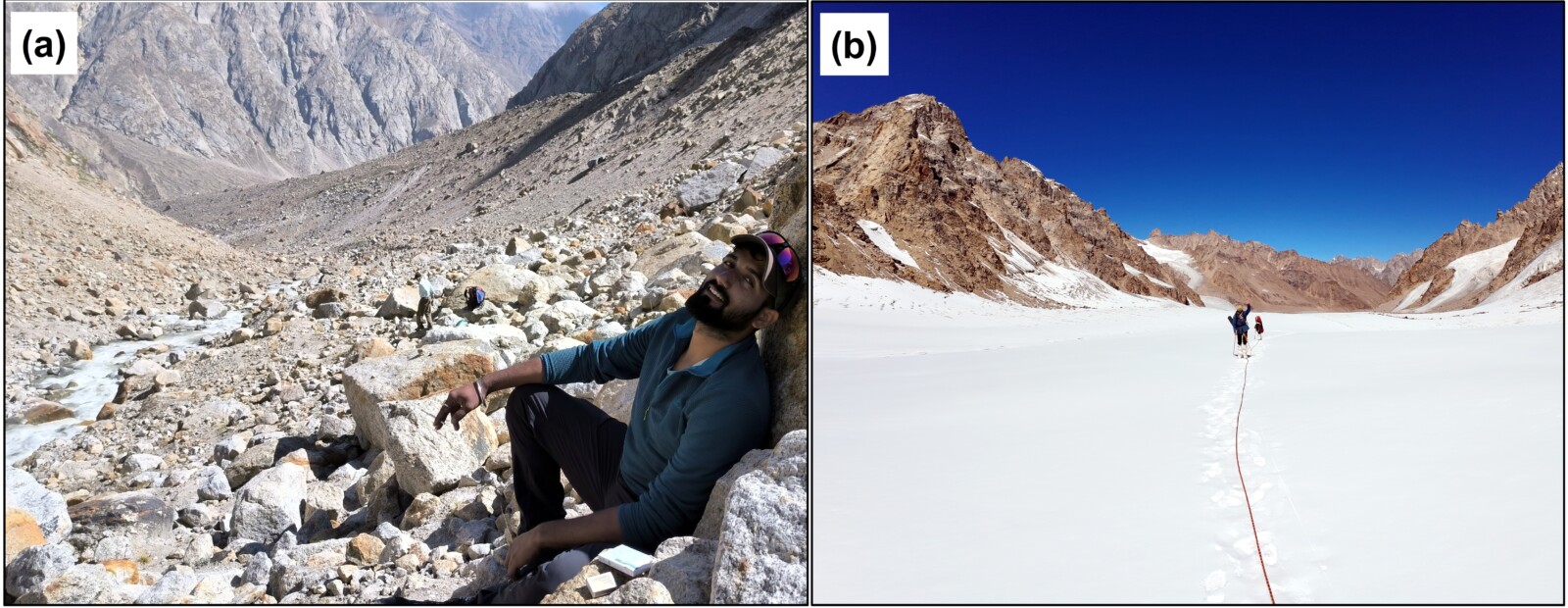

My first journey to the CSG

In 2018, I visited the CSG for the first time. As a novice field glaciologist, I had little idea what lay ahead. The trek began in the rugged landscapes of the Lahaul-Spiti region of Himachal Pradesh, where towering mountains and roaring rivers remind you of nature’s power and scale (Figure 6). The first stretch – a trek across a loose moraine and glacial debris – was exhausting and exhilarating. And then, there it was: the CSG, stretching like a frozen river beneath the mountain peaks of Papsura and Devchand – well-known to mountaineers.

Standing on the glacier for the first time, I was struck by its beauty. The surface cracked and shifted beneath my feet like a living organism. Everything was white, as far as my eyes could reach. It was all snow – pristine and endless. Here and there, jagged rocks pierced through the snow, their weathered grey breaking the monotony of white, like stars on a blank sky.

But as beautiful as the glacier was, it was also unforgiving. The cold seeped into my bones, and the thin, biting air made sleep impossible. I spent the night tossing and turning, the weight of exhaustion tangled with the throbbing headache born from high altitude. Each breath felt like a small battle, sharp and deliberate. Little did I know that this glacier would soon become the center of my academic and personal life.

Figure 6: (a) Initial trek section with moraine, debris, and stream. (b) Landscape with towering peaks (Credit: Sachin Kumar Thakur (a); Himanshu Kaushik (b)).

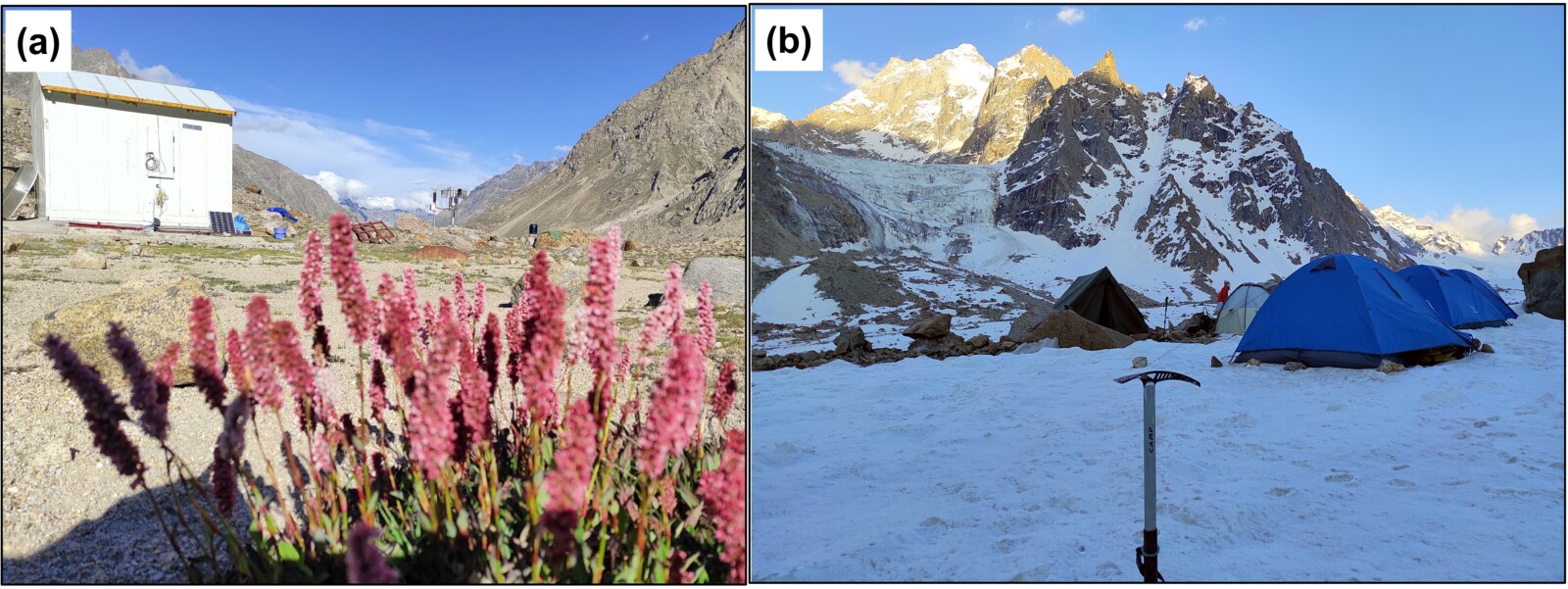

The base camp and high camp experience

The journey to the CSG does not end when we reach its edge – it is just the beginning. Each expedition requires establishing a base camp at approximately 3,800 m a.s.l, where our team prepares for two to three days for demanding fieldwork. The base camp is both a logistical hub and a home away from home, nestled in a stunning yet unforgiving landscape (Figure 7a). Base camp life involves a balance of discipline and adaptability. We rise with the sun to make the most of daylight, preparing for long treks and intensive data collection.

Figure 7: Rugged beauty of the campsite: (a) Base camp (~3800 m a.s.l.) and (b) high camp (~4700 m a.s.l.) on the CSG (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik).

The trek from base camp to high camp, which often involves carrying scientific instruments, can take up to six hours over rocky, icy terrain. The porters – the backbone of moving and managing our research logistics – are indispensable to the team as they navigate these challenging paths while carrying heavy loads. At this camp, camaraderie flourishes. I still remember a piece of wisdom shared by my colleague that has stayed with me ever since: “On the glacier, we are family. In any emergency, no one gets left behind. Everyone does their best to get through it together.”

The experience at high camp is markedly different from base camp, presenting its unique challenges at an altitude of approx 4,700 m a.s.l. (Figure 7b). Set on a medial moraine (a ridge of debris that forms where two glaciers or glacier branches meet and their lateral moraines, the debris along the glacier’s edges, merge – more details on moraines here) or on a snow surface, it necessitates meticulous planning to ensure safety and access to water. The cold, thin air and high altitude make even basic tasks feel monumental. Sleeping is typically tricky, with freezing temperatures and altitude-induced headaches compounding exhaustion.

Yet, there is magic here too. On clear nights, the Milky Way stretches across the sky, which is breathtaking and a reminder of the vastness of the universe and our tiny place within it (Figure 8). Moments like sipping a warm cup of chai after a demanding day or standing in silence under the starlit sky make the hardships worthwhile.

Figure 8: High camp with the Milky Way illuminating the Himalayan night sky (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik).

The 2022 mega heatwave year

Among all my field experiences on the CSG, the 2022 expeditions were the most potent reminder of the glacier’s fragility and the urgency to address climate change. That summer, a global heatwave left a lasting impact on the glacier (Hassan et al., 2024, here).

When we visited the glacier in September 2022, it offered a shocking view: what should have been snow-covered was bare ice riddled with crevasses and depressions (Figure 9, left panel). The glacier experienced significant mass loss, visible to the naked eye. Dark patches of exposed ice replaced the pristine surface. Each step was precarious as usual routes became inaccessible, forcing us to navigate the chaotic terrain. This year marked the highest mass loss on record, highlighting the severe effects of rising temperatures on Himalayan glaciers.

In contrast, in September 2023 a fresh blanket of snow partially filled crevasses, restoring stability (Figure 9, right panel). Walking felt safer, though hidden dangers lingered beneath the snow. This improvement underscores the glacier’s resilience yet highlights the urgent need to mitigate climate change. For me, the 2022 heatwave remains a pivotal moment, revealing the glacier’s vulnerability and the need for action.

Figure 9: CSG after the 2022 mega heatwave (left) and one year later (right), taken from the same position (Credit: Himanshu Kaushik).

Life lessons taught by the glacier

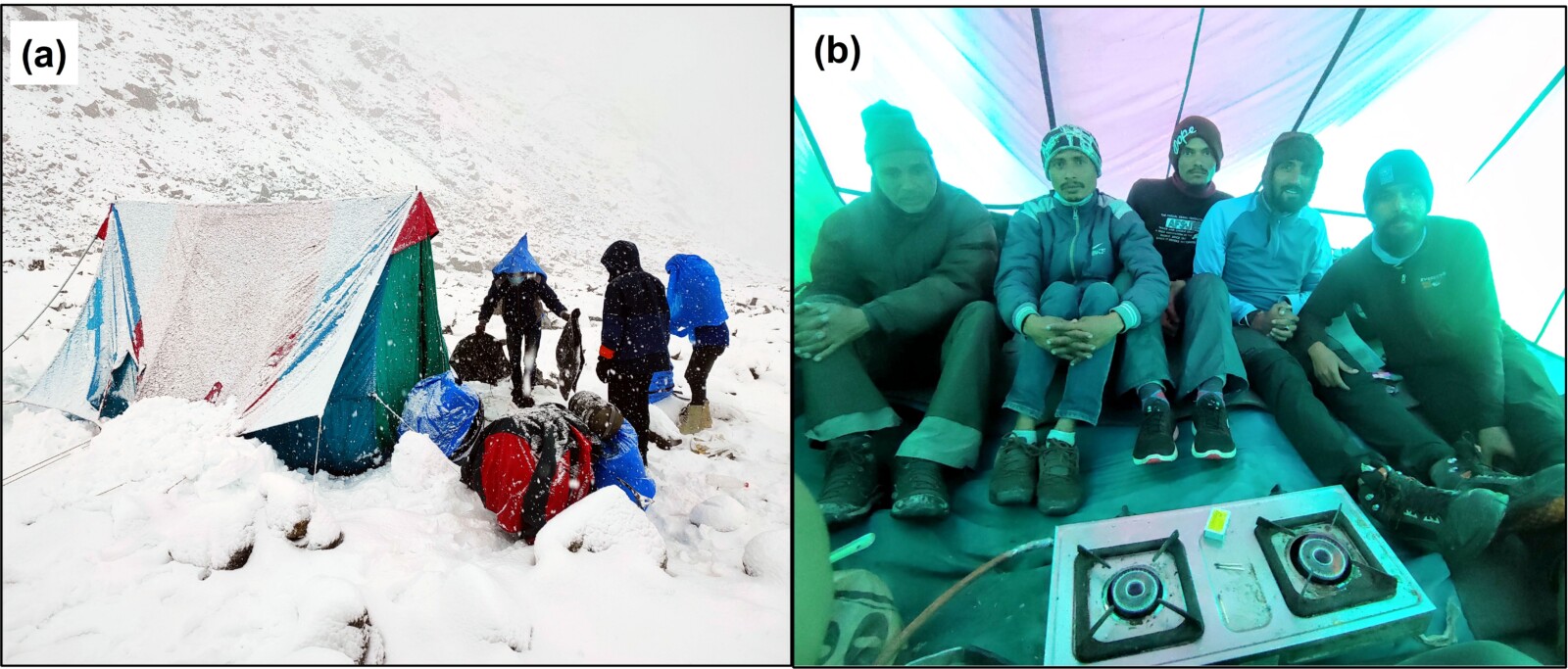

Beyond documenting the glacier’s transformation, our time on the glacier was shaped by unexpected trials and moments that tested our resolve and reminded us of the unpredictable nature of living on the ice.

One night during an early expedition, our cooking stove accidentally sparked a fire inside our tent. The following chaos – a spilled can of oil, freezing winds, and a partially burned tent – tested our resilience. But as if that was not enough, a snowstorm rolled in, battering our already compromised shelter and making things even worse. Scorched from the fire, the roof could not protect us fully, and the freezing air found its way inside the tent. It was a surreal combination of fire and ice, something we will not forget. It showed how unpredictable life on the glacier could be. We huddled in the damaged tent with limited resources, warming our hands over the stove while sharing stories to pass the long, cold night (Figure 10).

That night, amidst the harsh realities of glacier life, we found warmth in each other’s company. By morning, the storm had passed, and despite being exhausted, we felt stronger as a team. The experience of working on glaciers encouraged me to realize that glacier research is not only an opportunity to advance science but also a way to form bonds with others, develop resilience, and acquire life skills.

Figure 10: The unforgettable night of the September 2021 expedition (Credit: Navin Thapa (a); Himanshu Kaushik (b)).

Concluding thoughts

The experiences gained on the CSG have led to various outcomes, including an improved understanding of the glacier system and the acquisition of life lessons. This journey transformed me from a mere admirer of glacier landscape to a curious learner trying to understand glaciers’ responses to changing climate dynamics. Glaciers are not just majestic formations; they are crucial sources of freshwater, and studying them provides critical insights into climate change. CSG is shrinking due to rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns.

These trends significantly impact local hydrology and the communities that rely on glacial meltwater for drinking and agriculture. As I progress through my PhD, I’m eager to keep exploring CSG responses to a changing climate. Like many Himalayan glaciers, its future hinges on research and collective action.

Further reading

-

Azam, M. F. et al. (including H. Kaushik) (2024). Reanalysis of the longest mass balance series in Himalaya using a nonlinear model: Chhota Shigri Glacier (India). The Cryosphere (here).

-

Mandal, A. et al. (2020). Understanding the interrelationships among mass balance, meteorology, discharge, and surface velocity on Chhota Shigri Glacier over 2002–2019 using in situ measurements. Journal of Glaciology (here).

-

Hassan, W.u. et al. (2024). Unveiling the devastating effect of the spring 2022 mega-heatwave on the South Asian snowpack. Communications Earth & Environment (here).

Edited by Leah Sophie Muhle & David Docquier

Manisha Singh

Such a wonderful notes

Manisha Singh

It is soo much informative for our knowledge towards the glacier life.

Himanshu Kaushik

Thanks 😊

András Zlinszky

Satellite image compare of the glacier in September 2022 and 2023: https://link.dataspace.copernicus.eu/ybis

Kudos for the post, well written – keep the hard work up!

Himanshu Kaushik

Thank you so much! Really glad you enjoyed the post.

Raj

Beautiful. I have been to this Glacier in 2020. Also saw the Automatic Weather Station.

Nikhil Pandey

Well-articulated blog. Kudos to you and we want more of such stories, keep posting