Since several decades, there’s a lot of discussion in the permafrost ecosystem community on “rewilding” and “return to a natural state” in order to protect ecosystems and to reduce the impacts of climate change. Reindeer and other herbivores influence the insulation regime of the ground and could thereby preserve the frozen state of permafrost ground. Is there a way to utilise this effect to our benefit, and make wild animals the “ecosystem engineers” of the Arctic?

How are wild animals helping the climate?

Well, frozen ground is very temperature-dependent, so the lower the ground temperature, the more likely it is that only shallow thaw down from the surface happens and so a large portion of the ground stays frozen. However, over the last decades, researchers (Wilcox et al. 2019, Stimmler et al. 2023) have measured a trend of increasing thawing of the top layer, called the ‘active layer’ (mostly a few centimetres to several meters thick). And along with that, organic material that accumulated over millennia also became unfrozen, and soil organisms could feed on it, producing and releasing CO2 and methane into the atmosphere, which further boosts the global warming. This so-called Arctic amplification, a feedback loop in the carbon cycle, is one of the key drivers in global warming. So, keeping this stuff frozen solid would be nICE.

Scientists discovered that ground temperature is strongly dependent on the insulation at the surface by snow in winter and vegetation in summer. Huge piles of snow, which are quite common in the Arctic, create an air-filled buffer between the cold winter air and the summer-warmed ground and thus insulates the ground. The ground eventually still gets cold enough to freeze, but the colder the better. If animals, especially large herbivores looking for food underneath the snow, trample and dig through this layer, the cold winter air reaches the soil directly and cools it down to much lower temperatures (Pennisi 2018). In return, when we start into the next summer season, the ground will now take more time to reach the thawing point, and the unfrozen time until next winter will be shorter. This reduces the time during which the soil organisms can produce and set free greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, as their activity is greatly reduced in frozen conditions. To gain such insights, experimental sites in the Arctic are required, and probably the most famous one is the Pleistocene Park in northeastern Siberia. Here, large animal populations were introduced to a tundra landscape 25 years ago, and their impact on the ecosystem has been monitored and evaluated continuously.

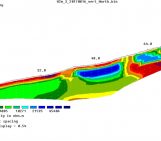

Large animals like reindeer have another effect: they feed and trample on the vegetation when there is no snow around (i.e. in summer or in areas where no or little snow accumulates). The common, sturdy tundra vegetation (for example dwarf birch and crow berries) is not very fast-growing and therefore has a hard time to recover from any damage taken. Other plant species (such as tufted hairgrass) that are more resilient and fast-growing fill in the gaps, slowly transforming the tundra into a steppe-like, grassy vegetation (Windirsch et al. 2022, Kristensen et al. 2022), much like a cold Serengeti (Fig. 2). Whenever snow falls on top of these grasses, the grass will simply tip over under the burden so in contrast to tundra vegetation, there is only few air-filled spaces underneath the snow layer that would insulate the ground from the blistering cold. However, while sturdy tundra vegetation protects the ground to some point against summer heat by casting shadows on the ground, the bendy grasses tend to not do this.

Fig. 2 – Vegetation depending on grazing intensity in northern Finland. [Credit: T. Windirsch]

But doesn’t the ground get warmer in summer then?

Well, here’s the trick: as long as the number of days below the freezing point is larger than the number of days above the freezing point, there will be more soil-refreezing after summer than thawing during summer – leading to a net decrease of the active layer, and reducing the availability of organic material for soil organisms.

Plus: The fast-growing grasses, or at least large parts of each plant, do not survive winter, and therefore will grow all new in the next summer. By doing so, they take up CO2 from the atmosphere, trapping it inside their biomass. The dead plant remains laying on the ground will eventually be pressed into the top of the soil by trampling animals, slowly incorporating them into the active layer and hopefully freezing them during next winter. So the large herbivores help to store more carbon in the soil!

Great! Now, can we just put animals all over the tundra?

In theory: yes. But of course, all these animals need to be adapted to cold and harsh climate, so the most suitable animals would be bison, reindeer, moose, and probably horses. You see, these are not easy-to-tame animals, and covering the whole Arctic tundra with a dense-enough animal population (roughly 50 large herbivores per km²) requires roughly half a billion animals. And also, these ecosystem transformations take time, at least some decades, until they are effective. The very high animal densities needed for such effects are therefore only feasible on a small scale and in locations where thawing ground is especially problematic. Regions with livelihoods and therefore existing infrastructure are especially at risk.

Having all these animals around requires some degree of care, which involves humans being present in the nearby area. But at the same time, the rewilding should not interfere with local land use and named infrastructure.

So, in summary: increasing the number of (species-diverse) animal herds across the Arctic in sort of a farming approach, can help reducing carbon emissions from Arctic ground.

But what about animal farts?

Of course, there are greenhouse gas emissions from the animals. These are different between species, and depending on their exact diet. Increasing the number of animals, increases the number of greenhouse gas emissions from animals, but at the same time, it also increases the availability of meat on the menu for us humans. How about we take this as a chance, to cut back on industrial-style cattle farming, that produces enormous amounts of greenhouse gases without any real benefit, apart from the meat? On a global market, it doesn’t really matter where exactly the meat is produced, so increasing animal numbers in one area means we are able to reduce animal numbers in another without taking meat off the market. And if this new style of animal farming is beneficial for the climate at the same time, what else is there to wish for?

Bonus: The meat of bison, reindeer etc. is much healthier than “normal” beef – and for the meat lovers: it tastes absolutely great!

Further reading

Kristensen et al. 2022: Soil Carbon Dynamics Across A Windthrow Disturbance Sequence In Southeast Alaska

Pennisi 2018: https://www.science.org/content/article/rewilding-landscapes-rhinos-and-reindeer-could-prevent-fires-and-keep-arctic-cool

Stimmler et al. 2023: Pan-Arctic soil element bioavailability estimations

Wilcox et al. 2019: Tundra shrub expansion may amplify permafrost thaw by advancing snowmelt timing

Windirsch et al. 2022: Large herbivores on permafrost— a pilot study of grazing impacts on permafrost soil carbon storage in northeastern Siberia

- The Zimov Pleistocene Park

- Griswold-Tergis: Check out the Pleistocene Park movie here.

Edited by Lina Madaj and Loeka Jongejans

Torben Windirsch is a geoecologist working in permafrost biogeochemistry and Arctic ecology. His vision is to find ways in which we as humankind can help fighting global warming by supporting and empowering traditional land use practices. While looking at potential strategies from a natural science point of view, Torben cooperates with people from the Arctic, as well as with researchers from social science to develop inclusive frameworks on how a sustainable Arctic might look like in the future. For questions, comments and ideas, please contact Torben at: Torben.windirsch@gmail.com