Darkness. Freezing cold. Thin layers of ice cover the wide Arctic Ocean. It is the time of the last dusk. You can almost see Fenris wolf chasing the sun to devour it, almost hear his howling as darkness falls. Fimbulwinter has arrived. But what is this? A flower? Out here on the Arctic Ocean? This is strange, so let us take a closer look at the mystery of the ice-cold rose.

Where the Wild Roses Grow

In winter, when it is dark and cold, you can sometimes find them: frost flowers. Under calm and very cold conditions, these 3-4 cm in diameter large ephemeral structures can suddenly appear on ice surfaces. This happens when water is expelled from a forming ice surface, vaporizes in the cold air and crystalizes into very fine and intricate structures that look almost like flowers (Figure 2).

Out on the open ocean, for example the Northern Barents Sea, this happens when new ice forms and barely covers the ocean. These forms of ice are called black or white Nilas. Thin layers of ice that grow from black (or better: translucent) to white and then ultimately turn into thick sea ice. On these Nilas, frost flowers form when brine is expelled in the freezing process and crystalises. Since these brines are rich in salts and other chemical compounds, this means that the frost flowers are as well. They are also suggested to foster interactions between the ocean, sea ice, and the atmosphere and might be the major source of salinity in aerosols. But besides that, they also contain bacteria and archaea, which are transported into the frost flowers when they are created. But which bacteria and archaea can be found in there? To find out, my colleagues collected frost flowers on a winter expedition in the Northern Barents sea (Figure 3) and investigated their microbiome. Since these flowers are rare, ephemeral, and fairly difficult to collect, you can imagine how happy I was to get some, even if it is just a single sample.Microbes in the dark Arctic frost flowers

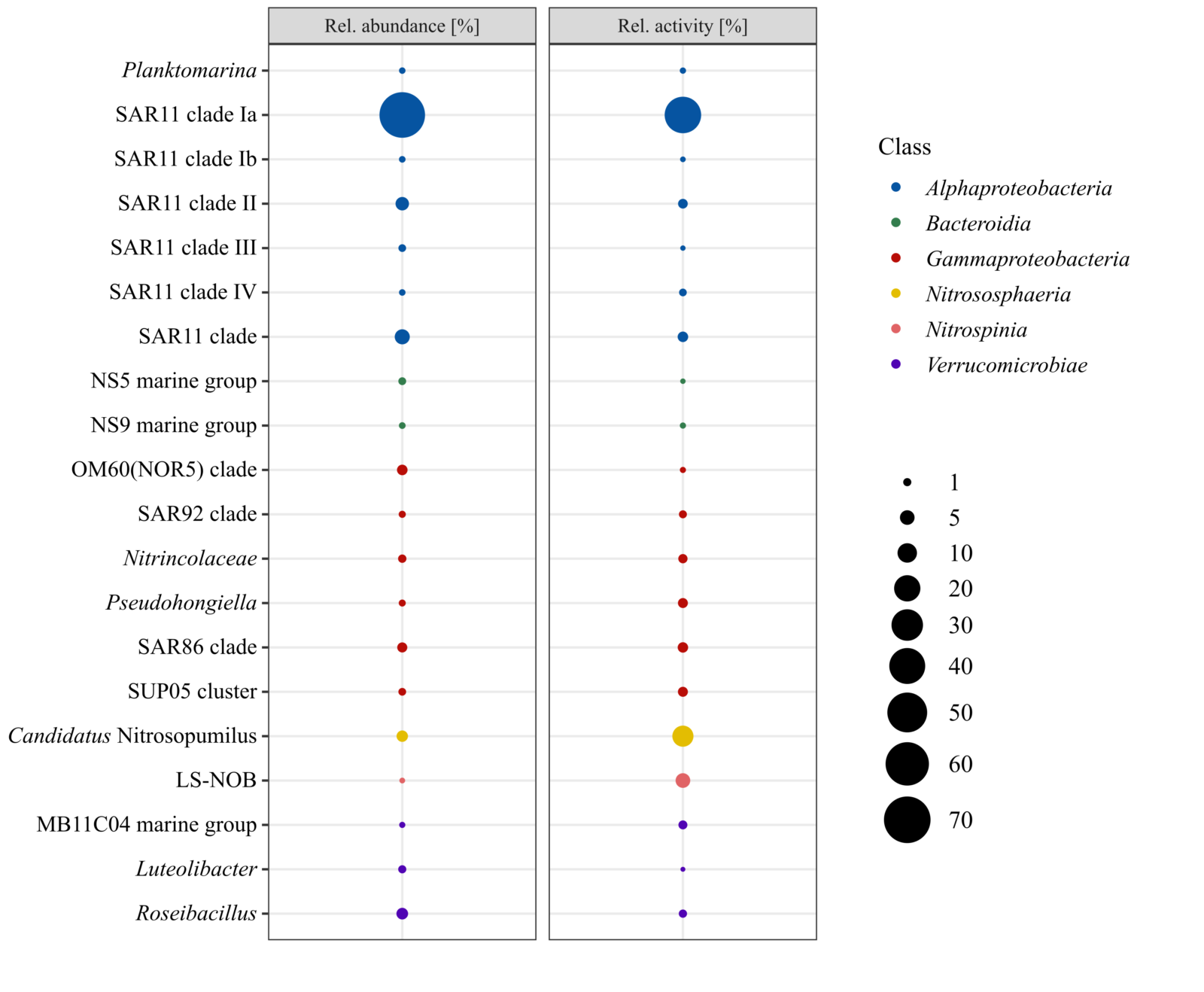

Previous studies have looked into frost flowers from coastal areas and found rather rare marine bacteria, like Rhizobia and Propionibacterineae in Alaska. But they also found more marine taxa like SAR11, Nitrospina, and Rhodobacteraceae in Greenland. But how would that change in the open ocean and in the dark Arctic winter? Let’s take a look. I used the 16S rRNA gene, a name tag for bacteria and archaea, and looked at their abundance . In Figure 4, it is clearly shown that the dominating organism was an Alphabacterium called “SAR11”. This is a peculiarity when you study microbes. Those that are not described before get these funky names until somebody can actually give them a real name. This sounds a bit strange, especially since members of the SAR11 clade (combining clades Ia, Ib, II, etc.) are among the most abundant taxa on Earth. What you need to know about them is that they are not very active and that they are small, even for bacteria. And then, we also find archaea, who even have something close to a real name: Candidatus Nitrosopumilus. Not really a name, but at least a candidate for a name. Yes, microbiologists are weird people and so is Cand. Nitrosopumilus. Another very small microbe. Apart from being abundant, Cand. Nitrosopumilus are also active. How can you tell? I estimated the activity based on the number of 16S rRNA copies they have in their cells, which one can use as a proxy for the relative activity (right side of Figure 4).

Figure 4: The bacterial and archaeal community composition and relative activity based on 16S rRNA sequences for the 20 most abundant taxa. [Credit: Thiele et al., 2023]

Nitrification by these small microbes

These archaea I found are small and they only live in dark places, such as the deep sea or the surface of the Arctic Ocean in winter, as previously reported. But not only that: they also “eat” ammonium and transform it into nitrite, a process called nitrification. Nitrification is completed with the transformation from nitrite to nitrate. This step is done by Nitrospinia, like members of the LS-NOB clade, which I also found in the frost flowers. So, I found a community of small bacteria and archaea, of which some produce nitrate from ammonia. While the nitrification has been suggested for Arctic sea ice microbiomes in winter, the question remains why all microbes in there are so small. Probably, it is a combination of high abundance of the small bacteria and archaea in the sea water, exclusion through the size of the brine channels in the freezing frost flowers, and the absence of yummy food for the big microbes in the frost flower. But since I only had one sample and I am the first to look into these open ocean frost flowers in winter, it might be good to take a second look and confirm what I found. And since the ice production apparently increases, let’s hope for more frost flowers in the future.

Further reading

- A winter-to-summer transition of bacterial and archaeal communities in Arctic sea ice. Thiele, S., Storesund, J. E., Fernández-Méndez, M., Assmy, P., & Øvreås, L. (2022). Microorganisms, 10(8), 1618.

Edited by Loeka Jongejans

Stefan “Zwiebel” Thiele is a postdoc at the University of Bergen, Norway. He investigates bacterial and archaeal communities in Arctic environments such as sea ice, the marine pelagic environment or pingos in Svalbard. In addition to the polar work, Stefan also works on smaller projects regarding other bacterial and archaeal communities, e.g. in cave sediments in the Bahamas. In his free time, he conducts a second Master of Science in Environmental Science, where he works with microplastic in the ocean. Contact Email: stefan.thiele@uib.no

Stefan “Zwiebel” Thiele is a postdoc at the University of Bergen, Norway. He investigates bacterial and archaeal communities in Arctic environments such as sea ice, the marine pelagic environment or pingos in Svalbard. In addition to the polar work, Stefan also works on smaller projects regarding other bacterial and archaeal communities, e.g. in cave sediments in the Bahamas. In his free time, he conducts a second Master of Science in Environmental Science, where he works with microplastic in the ocean. Contact Email: stefan.thiele@uib.no