This miniseries features the tradition of ‘PhD hat’ making in German research institutes and universities. For those of you unfamiliar with this idea (as I once was), this is one of the final milestones a graduate student has before they are officially a “Dr.”. Upon the successful defense of a thesis, the labmates of the PhD student craft a graduation hat from a mishmash of scrap cardboard and memorabilia. Hours of work go into these beloved pieces, and you can often find these hand-made creations fondly perched on a shelf in faculty’s offices. Here, we talk with several researchers who work within the cryosphere sciences to get a tour of their PhD hats. In the last posts, we ‘herd’ about Torben’s arctic herbivore hat and took a tour of the Nitrogen cycle with Tina through her microbiology hat. This month we sit down for a double-hat feature with Izabella and Ramesh who both study boreal permafrost landscapes through time.

For the third post in this series we talked with Dr. Izabella Baisheva (she/her), and Dr. Ramesh Glückler (he/him). Both researchers are recent graduates from the Alfred Wegener Institute and submitted their thesis to the University of Potsdam last July (Figure 1). Izabella was also affiliated with the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk (NEFU) during her time as a PhD student.

In their PhD thesis work, both researchers studied alaas landscapes – a dynamic arctic system that is underlain by ice-rich permafrost and characterized by thermokarst lake formation. Izabella’s thesis research involved analyzing lake sediment samples from eastern Russia (Yakutia) to reconstruct the environment around the lakes thousands of years ago. For her thesis “Past and present environmental conditions in Yakutia – a (paleo)ecological study using lake sediments” she identified the plant species using their DNA that she extracted from the lake sediment, as well as other proxies like diatom microscopic analyses. With lake sediment samples from the same region, Ramesh used a mix of laboratory and modeling methodologies to study the history of fire in the region. His thesis “Long-term changes of wildfire regimes in eastern Siberia” contributes to efforts of advancing our ability to understand fire patterns in the subarctic today.

Ramesh and Izabella first met during their field work in Siberia as members of a 30+ member expedition crew in 2021. Later, they started dating and are now a married geoscience dream-team. During this interview, we realized that their PhD hats have a lot in common, too!

Hi Izabella and Ramesh, can you tell us what your original thesis research question was? Did it change over time?

Ramesh: The original title of my PhD project was ‘Past and Future Forest Fires in Siberia’. For this work we used lake sediment to analyze past wildfires, and then I implemented these findings into an individual-based forest model. I had initially planned to study potential fires of the future. But it turned out it is not an easy task to simulate the future without fully understanding what happened in the past. So, my ‘past and future’ topic is more about studying the drivers of Siberian wildfires of the past.

Izabella: When I began my PhD, I had initially wanted to see how the Soviet Union’s policy of agricultural collectivisation affected the permafrost landscape that is characteristic of Yakutia – the alaas. However, the methods I ended up using for my thesis measured environmental changes within the alaas on larger (thousands-year) timescales – which did not capture the specifics of this very recent time period.

In Izabella’s home region of Yakutia, family groups live among the permafrost-based lakes of the alaas landscape. The lakes provide a source of fresh water for families, and the cattle they raise. Izabella keeps memories of the summers she spent with her grandparents in the haymaking season of the alaas, and witnessed the traditional lifestyle of how people live with the alaas of their ancestors. With the collectivisation of the Soviet Union, populations around alaas formations became denser and put strain on the fresh water supply. Due to these agricultural policies, as well as the warming climate, the freshwater lakes are becoming increasingly brackish and could desiccate. People traditionally gather the fresh water from the lake surface. However, to adapt to the increasingly brackish water people now gather the water primarily in the winters as ice. When brackish water freezes, fresh water stays afloat as ice and salt get sent to the bottom of the water column.

Figure 2: Izabella (left) sampling from her field site in 2021. Ramesh (right) holding a lake sediment core. The clear top half of the core is water, and the bottom half are the layers of mineral and organic matter that have accumulated on the bottom of the lake. Both researchers use these lake sediment cores to explore the alaas landscape of the past and present. [Credit: Ramesh Glückler, Amelie Stieg]

Were there any surprising findings from your work?

Ramesh: I found some surprising results by combining lake sediment core analysis (using laboratory methods such as sieving out charcoal and pollen from the sediment to uncover fire occurrence and vegetation present at the time) and modeling. We found that high fire activity coincides with more ‘open’ forest landscapes in Yakutia. This is interesting when we consider this in the context of our rapid climatic change and how it may increase tree mortality in Siberia. The increased tree mortality might be caused by biological invasions (such as insects) affecting trees or an increase in fires themselves. If these events create a more open forest landscape, it could positively reinforce a more intense fire regime in this subarctic region (Figure 2).

Izabella: A cool finding from my PhD is that I observed a lake depth shallowing stage of alaas formation that could be important to include in the currently recognized stages. Alaas landscapes have been thought to have four defined formation stages. In other systems – such as in the Batagay – the permafrost thaw waters flow outwards in rivers, but here the water stays and results in lake formation (Figure 2). The final stage of formation is the alaas stage, which gives the landscape its name.

Izabella found that between the ‘tyympy’ and ‘alaas’ stages, many lakes in her study region go through an extended period of shallowing. In her thesis she proposes naming this the ‘satagay’ stage as nod to the Indigenous peoples of the region, who called this stage an ‘unsettled’ form of the alaas.

Can you give us a tour of your PhD Hat?

Ramesh: Fire Truck

The fire refers to my fire ecology topic, but the hat-crafting people put the little fire truck there because during my PhD, I joined the volunteer fire department here in Potsdam (Figure 3). I wanted to see actual vegetation fires up close to get an idea of how it behaves as I had to implement fire as a process in a model. Also, this provided a very different perspective on the topic of fire!

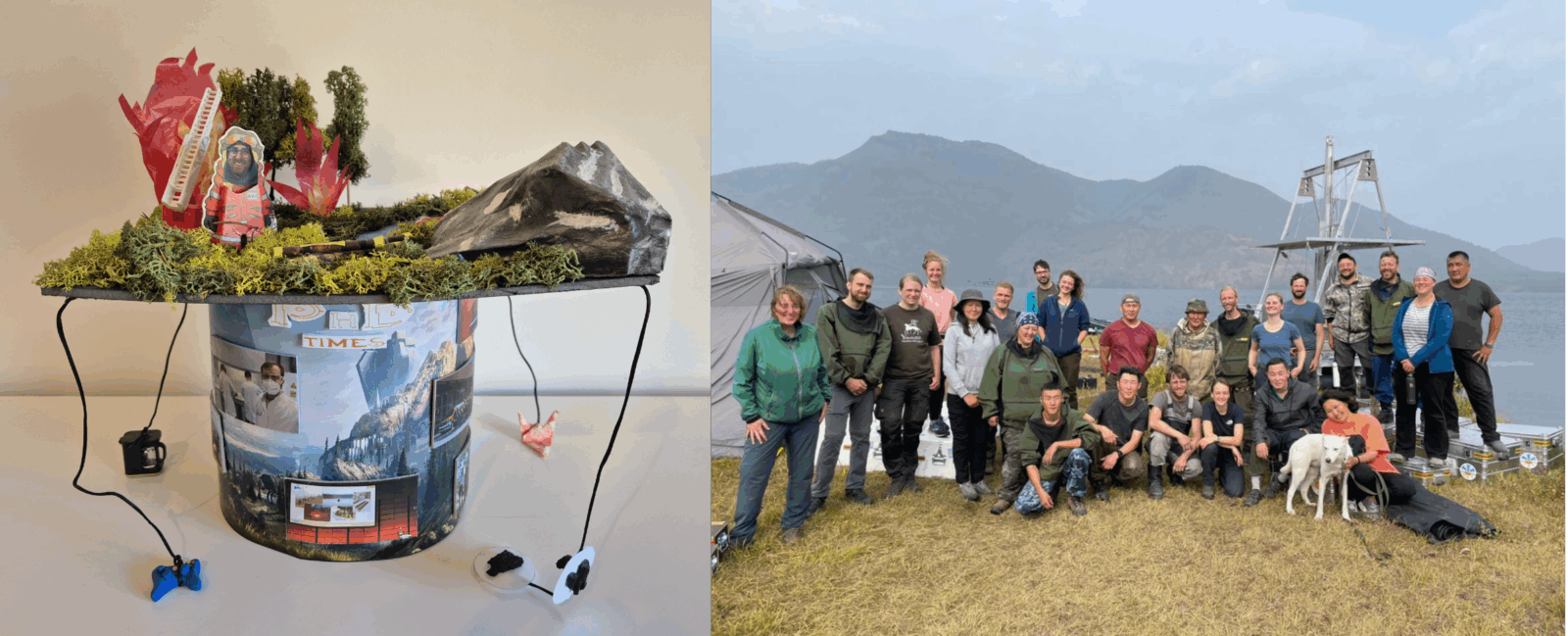

Ramesh: Expedition Group Photo

This picture in particular is one I want to highlight. It’s from our big expedition. We’re not all here in this photo, and there were more people involved in the expedition, but I think this is a cool picture because this expedition really was a major highlight of my PhD and a major experience in my life, and I am thankful to everyone involved (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Ramesh’s PhD Hat, with the ‘fire’ in view. On the backside of the hat is the expedition group photo, featured here on the right panel. [Credit: Ramesh Glückler, Yakutia 2021 Expedition Team]

Here we see this hut-looking object – this is a balagan (Figure 4). It is a traditional dwelling of the Yakut people. For my PhD, I was investigating the landscape that I come from, and it makes the topic kind of personal. Alaas means ‘home’ for the Yakut people, but it also refers to the thermokarst depression that the permafrost thaw forms. Now I use my research to look back to the time where and how the alaas was formed, and it is just so interesting because it takes ~15,000 years for these to develop.

Izabella: Hunter the dog

This is my dog, Hunter. I missed him so much during my PhD time in Germany, and I was always speaking about him so highly that my colleagues put Hunter on the hat (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Izabella’s PhD Hat, with the balagan and Hunter on the left side of the hat. The images dangling from the corners of her hat are examples of some of the diatoms found within the lake sediments. Hunter the dog is featured in the image on the right. [Credit: Izabella Baisheva]

Izabella: I was surprised that we had the same mountain on both of our hats (Figures 3 and 4). When our group was making the hat for Ramesh we had planned to mostly include the Yakutia expedition landscape, but also to represent the other expedition Ramesh took to the Dachstein mountains.

Ramesh: Ah this is Dachstein? I didn’t realize!

Izabella: Yes, our colleague Sarah Haupt made the ‘mountain’ with paper maché from egg cartons for Ramesh’s PhD hat. But what I didn’t realize is that she had cut this ‘mountain’ in two. She quietly kept the second half to put on my own hat since I was on the Dachstein expedition team as well (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Izabella and Ramesh’s hats as seen from above, with the shared ‘Dachstein’ [Credit: Izabella Baisheva]

Readers, stay tuned for next month’s installment of this miniseries, in which we will take another tour of the cryosphere through the PhD hats of those studying our icy planet.

Further Reading

- Looking for a way to stay connected to this topic? Follow @egu-cr.bsky.social on BlueSky to make sure you won’t miss any new episodes. Ramesh @rglueckler.bsky.social is also active there. Both Izabella and Ramesh you can also find on ResearchGate.

- For more details on the topics covered on these PhD hats, check out some of Ramesh’s and Izabella’s publications:

- “Holocene wildfire and vegetation dynamics in Central Yakutia, Siberia, reconstructed from lake-sediment proxies” using charcoal particles within the sediment to unravel the region’s fire history (part of Ramesh’s PhD)

- Izabella looked at the ages of the lake sediments and what local plants were growing in and around the alaas lakes in her paper: “Permafrost-thaw lake development in Central Yakutia: sedimentary ancient DNA and element analyses from a Holocene sediment record“

- A summary of Ramesh’s PhD findings was recently published as “Long-term changes of wildfire regimes in eastern Siberia: an evaluation based on lake sediment indicators and individual-based modeling“

- If you haven’t read it yet, check out the other episodes of this miniseries “Cryosphere Caps: PhD hats and the researchers that wear them”

- Episode 1: The arctic herbivore hat of Torben Windirsch

- Episode 2: The microbial ecology hat of Tina Sanders

Edited by Leah Sophie Muhle and Lina Madaj