This miniseries features the tradition of ‘PhD hat’ making in German research institutes and universities. For those of you unfamiliar with this idea (as I once was), this is one of the final milestones a graduate student has before they are officially a “Dr.”. Upon the successful defense of a thesis, the peers of the PhD student craft a graduation hat from a mishmash of scrap cardboard and memorabilia. Hours of work go into these beloved pieces, and you can often find these hand-made creations fondly perched on a shelf in faculty’s offices. Here, we talk with several researchers who work within the cryosphere sciences to get a tour of their PhD hats. Today, we ‘herd’ from a researcher who’s PhD work investigated how large herbivore presence influences greenhouse gas emission from arctic soils.

For the first post in this series, we sit down with Dr. Torben Windirsch (he / him). Torben is a geoecologist who completed his PhD thesis work with the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in 2024 (Fig. 1). His thesis investigated the effects of large herbivore presence on carbon stocks in permafrost soils. He continues working to implement the findings of his PhD thesis today as a Research Fellow with the Research Institute For Sustainability (RIFS) in Potsdam, Germany. These days, his laboratory findings offer insights that contribute to ongoing discussions on best practices for Arctic land use, especially traditional forms of land use (such as reindeer herding), with various international partners, focusing on livelihoods in northern Fennoscandia.

Hi Torben, can you tell us what your original PhD research question was? Did it change over time?

My research question was “How do large herbivorous animals impact permafrost ecosystems, and how do they affect carbon storage in the ground”. So, I was studying if there was more carbon in the grounds that were more heavily grazed as compared to those that were not (Fig. 2).

Originally, there was a work package in my PhD where I would have directly talked to people, such as reindeer herders. I wanted to know what needs to happen, or what circumstances would have to be met to increase herd size or increase access to areas they aren’t accessing right now, or what the animals’ specific preferences for grazing areas were. All this didn’t happen because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but apart from that, everything stuck pretty close to the original research question.

Figure 2: Torben in the midst of the field work that culminated in a successful PhD thesis, proving that sometimes life during fieldwork really is rainbows and sunshine [Credit: Torben Windirsch-Woiwode]

Can you give us a tour of your PhD hat?

Antlers

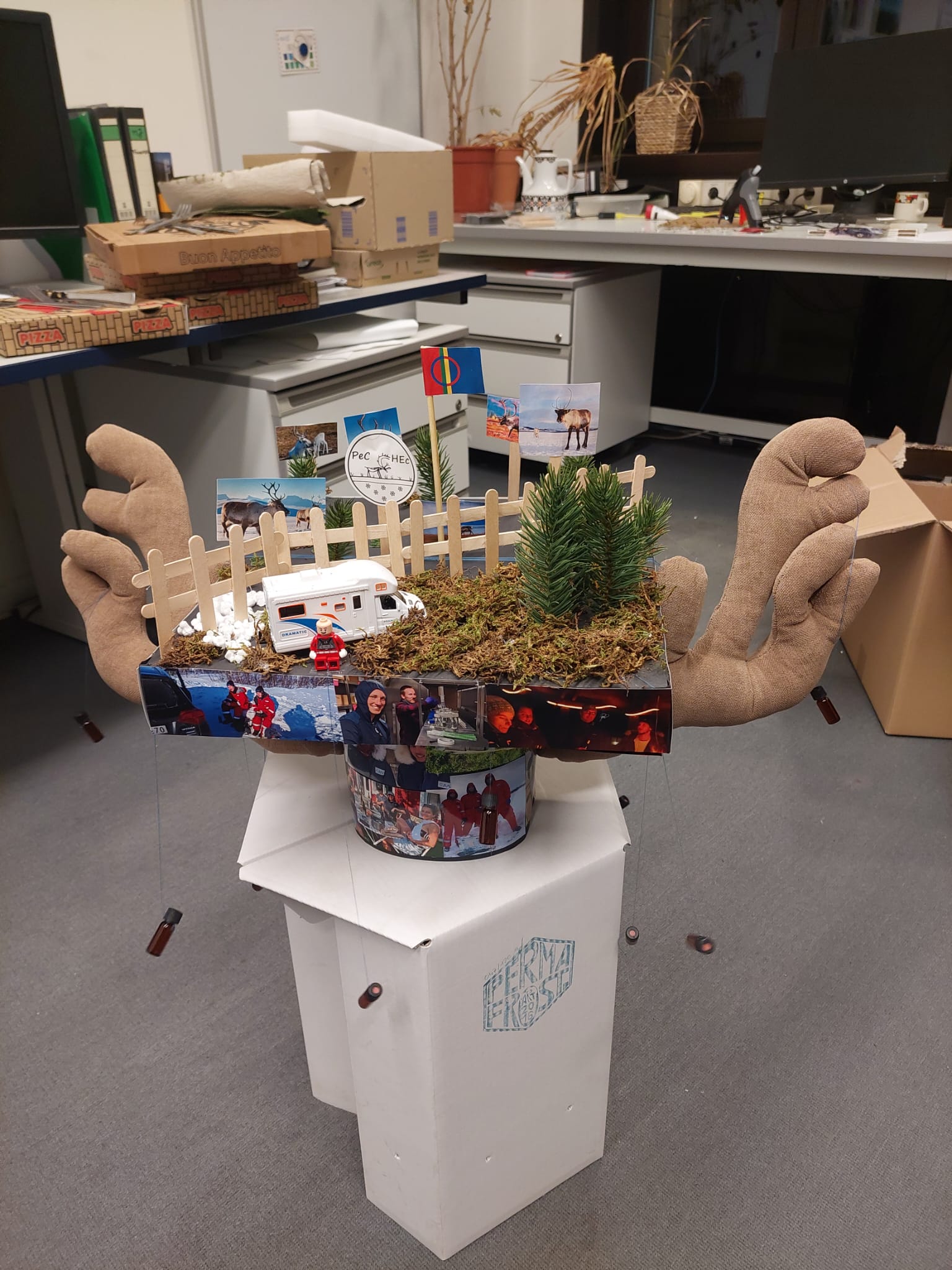

The most remarkable and unusual element in my hat is the reindeer antlers (Fig. 3). These were handsewn by Frieda (Torben’s then-labmate, a master student studying at the University of Potsdam).

Why Reindeer?

When drawing any implications from my results I focused on reindeer because they are the most managed and herded animals in the Arctic.

One of Torben’s field sites was a research station in Northern Finland that focuses on reindeer management practices, but he also worked in Pleistocene Park where several species of large herbivores roam the tundra of the Russian high Arctic.

Camper Van

One of the funniest details is the camper van (Fig. 3). We (Torben and his expedition partner Matthias Fuchs – now a postdoc at the University of Colorado Boulder) were thinking how to go to Northern Finland to work and to sample, during a global pandemic. We had to figure out how to do this with a mandatory two-week quarantine upon entry to Finland, so we rented a camper van and just bought food and everything for two weeks for the ferry ride to Finland and the drive from Helsinki to the field sites in the North. We used the two-week quarantine to complete our sampling plan. Then we took another four days driving south, meeting some colleagues on the way, and having our first warm shower within two weeks. Before that, we were bathing in the river and as it was mid-September, the water had a temperature of 3°C. It was fun, and refreshing!

Biomarker vials

I spent a lot of time in the biomarker lab because the sample processing just takes ages. I usually did sets of 12 samples, with two batches of six [Fig. 3; Biomarker analysis is a method that extracts the specific molecules (biomarker) out of soil samples to characterize the state of degradation, or reconstruct past environmental conditions. In combination with other laboratory methods, it is useful for permafrost soil analysis to see how frozen soils may change in a warming climate].

It takes about three weeks of full-time labor to complete one full batch. Most of the time you’re there just watching instruments, and chromatography columns. You’re running a clear liquid through a column and you’re adding another clear liquid and, in the end, you hope that the machine will have some results. Luckily, it did! And it was pretty clear that the measurements were very good.

If you’re curious about where Torben’s time spent watching the chromatography columns went, check out his publication.

Figure 3: The PhD hat Torben’s peers and labmates crafted for him. Here, the handsewn-antlers, camper van, and biomarker vials come together to help tell the story of Torben’s time as a PhD student at the Alfred Wegener Institute. [Credit: Fabian Seemann]

For those who just joined a lab group in Germany, or maybe want to bring this to their own lab group: What is something essential to include in a labmates PhD hat?

I think a PhD hat is a very personal thing to craft and it depicts what impressions you left among your colleagues. As for elements to include, I would have three must-haves, my examples might be very Arctic-specific though:

- It’s always great to include a 3-D object on top of the hat. This can be anything, and it can be quite silly. For me, it was the camper van, which represented a pretty unique aspect of my PhD, but also figurines of satellites, snow mobiles, boats, a bear (if you encountered one) or field equipment work great. If the candidate spends a lot of time in remote field locations, a tent is cool for example.

- Flags! I really like flags on a hat to show where this PhD was done. This includes both state flags, e.g. showcasing the different field sites included in a PhD (works also for remote sensing or modelling PhDs), as well as flags/logos of conferences and meetings attended, networks actively participated in.

- The dangling bobble! Modelled after the black bobble on traditional graduation hats, this element is an eye catcher without limits.

Thank you for your time Torben, and for taking us on a tour of your PhD hat.

To the reader, stay tuned for another instalment of this new miniseries as we tour the cryosphere through the PhD hats of those who study our icy planet.

Further reading

- If you like to know more about Torben’s research check out the block post he wrote for this blog: “Small step for reindeer – large leap for humankind?”

- You can also check out Torben’s most recent publication: “Can animal grazing help to reduce permafrost thaw?“

- If you like to get in contact with Torben to chat about reindeer or PhD hats, feel free to contact Torben directly: torben.windirsch@rifs-potsdam.de

Edited by Loeka Jongejans and Lina Madaj