The time I first set foot at the university, I didn’t expect that two weeks later I would be looking at a backpack more than half my size, turning my back to the shelter of our rental car and walking almost 100 km in the Norwegian Arctic. Howling winds, heavy backpacks, daunting bridges, and endless beauty – that’s how I would describe my first experience with glacier fieldwork.

I, Silje Waaler, started my PhD journey in August 2023 at the Department of Geosciences at the UiT, the Arctic University of Norway. As a part of my PhD project, I’m involved in the work carried out by the research group METALLICA. This acronym stands for “Meltwater release of heavy metals from glacier to ocean in a changing Arctic” and you can find more information on our project website. In METALLICA, we’re looking into the release of heavy metals, especially the toxic trace metal mercury, from glaciers to downstream systems such as rivers, lakes, and fjords. These heavy metals can be harmful to organisms, which makes it crucial to understand under which circumstances they are released from glaciers and how they act in the downstream environments. Because of the large diversity of glacier types, bedrock composition, and downstream systems we gather data from a broad variety of glaciers and the connected surroundings. However, answering these questions requires an extensive amount of fieldwork, spanning all seasons, to ensure that any changes are captured.

An Offer You Can’t Refuse

During one of the early meetings last year with my main supervisor and project leader of METALLICA, Prof. Jemma Wadham, she proposed the idea of getting some insight into glacier fieldwork straight away. Her Postdoc researcher, Sarah Tingey, was about to set off on a trip to the glaciers Sulitjelma and Salajekna. The ice cap from which the two glaciers flow is located on the Norwegian-Swedish border, close to the small mining city of Sulitjelma – a city previously inhabited by the Sami people. Being eager to get my hands dirty with glaciology, this approach suited me very well. A few days later we set off!

Left: me and my backpack at the first cabin – Lomihytta. Later on, the weight of the backpacks drastically increased as we sampled water and rocks along the way. Right: Sarah Tingey and I right before heading for the Magical Hut [Credit: Sarah Tingey]

One foot in front of the other

At this time, Sarah had already managed to collect samples from mainland Norway over the melting season starting from June last year and was used to the extensive work involved in gathering these precious samples. Me, being broad up in one of the flattest places on Earth, Denmark, had a long way to go.

We parked the car at Storelvvatn Powerplant with the wind dragging and pulling our fully packed backpacks and made our way towards Lomihytta – a small, cozy cabin owned by the Norwegian Trekking Association. After the short trek to the cabin, we decided that following the northern coast of Låmivatnet to a privately owned cabin, which exact location and state was unsure to us, would be too risky in the stormy weather. With the wind howling outside, we stayed in the cabin, planned our next move and waited for better weather. The next day, we started walking towards what, over the course of the night, we had named the Magical Hut due to its questionable existence.

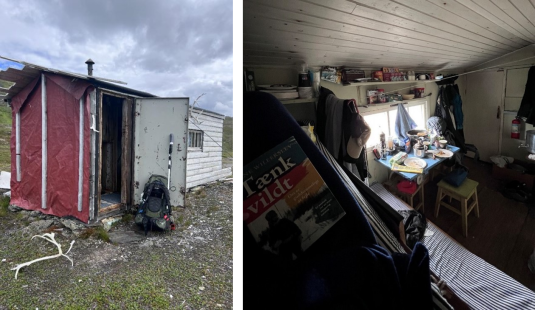

Left: the Magical Hut – Our second home on the trip. The cabin was well-equipped with a wood stove, a few rusty pots, and mattresses hollowed by the souls which had enjoyed this tiny safe haven in no-man’s-land before us. Keeping the door open is Sarah Tingey’s backpack with the discharge sensor sticking out. Right: view from the top bunk, also known as Sahara due to the high temperatures achieved through burning wood in the stove. Reading books, eating chocolate, and saving energy was the agenda of the day on which we were blown into the Magical Hut. [Credit: Silje Waaler]

Where the Giants Roam

This tiny cabin, placed on a promontory stretching into Låmivatnet, became our fix point during the following days. We spend a full day blown in, and a day hiking to the Sulitjelma glacier to sample meltwater there where it escapes the darkness of the subglacial environment and accumulates into a proglacial stream that flows down the mountain side into a lake, recognizable by its milky appearance due to high inputs of silty sediments. This was my first up-close encounter with a glacier. Being so close, feeling the cold katabatic wind swirling down from the inner parts of the ice cap and seeing the impact this icy giant has on its surroundings, lives vividly in my memory.

Left: portal of the Sulitjelma Glaciers. Here we sampled the subglacial meltwater as it exited the mysterious environment beneath the glacier. Right: the Salajekna Glacier on the Swedish side. This part of the ice cap is terminating into a proglacial lake making it very distinct from its twin sister – the Sulitjelma Glacier [Credit: Silje Waaler]

Follow the water

Our next assignment was sampling the water of the proglacial lake. In this lake, we could see just how much meltwater was accumulated as the water masses turn into a broad river engulfing lumps of smaller icebergs that were once attached to the lake-terminating Salajekna glacier. To assess how much water, heavy metals and nutrientsthese two glaciers release, we used non-toxic trace dye and a fluorometer capable of measuring low concentrations of the fluorogenic dye. These discharge measurements are essential when describing the impact that glaciers have on their surroundings.

Because of the delay from two days of bad weather, we decided to continue hiking to the Swedish cabins near Pieskehaure after sampling the proglacial lake. The rain was pouring down, but we managed to find a way through the soft sediments deposited by the glaciers and former landslides from the moraines – yet another example of the impact of glaciers. Soaked to the core, we were greeted at the Swedish cabins by the cabin host’s smiling face. She had been awaiting us for several hours. She took us in and showed us around, while Sarah and I, still wet through all layers, tried to hide the urge to just lay down where we stood.

Left: one of many scenic views on the trip with one of the wooden bridges that made river crossings much easier. Overlooking Låmivatnet, the Magical Hut is seen in the distance. Right: An incredibly long day at “the office” of following the water from the Salajekna Glacier to Pieskehaure on a rainy day [Credit: Sarah Tingey]

A Peripatetic Passage

The Swedish cabins were placed close to our last sampling location on the trip, Pieskehaure, which if you follow the lakes, streams and rivers will lead you into the deep forests of Sweden. Now, with backpacks full of filtered sediments, rocks, and water samples, we made our way back across the border from Sweden to Norway, towards Storelvvatn Powerplant and our rental car. Through the seven days we hiked and sampled, I got a profound respect for people doing fieldwork heavy research. When you’re reading a paper, you tend to forget just how much work is behind every single measurement – just how many borders theyresearchers crossed in order to push the boundary of our knowledge forward.

Once back in the warm and safe labs of the Department of Geosciences, the precious samples will be analyzed, providing crucial insights to the power behind these icy giants. Some of the samples collected on my very first glacier fieldwork experience will feed into my PhD project where I’ll investigate how silica is released from a broad variety of glaciers in Svalbard and mainland Norway to downstream systems.

Sarah Tingey and I on one of the rare sunny days, crossing the border into Norway after sampling at Pieskehaure on the Swedish site of the downstream system of Sulitjelma/Salajekna. Big plus: no delays due to passport controls here. [Credit: Sarah Tingey]

Further reading

- Our research project: METALLICA

- Article on impact of glaciers on downstream systems

Edited by Loeka Jongejans