The Karthaus summer school on Glaciers and Ice Sheets in the Climate System has a long history of training many generations of PhD students, thus forming professional networks that have lasted throughout their careers. The Karthaus summer school has been described in detail in a previous Cryoblog post. Here we want to focus on the story of a glacier…

Hochjochferner, a retreating glacier

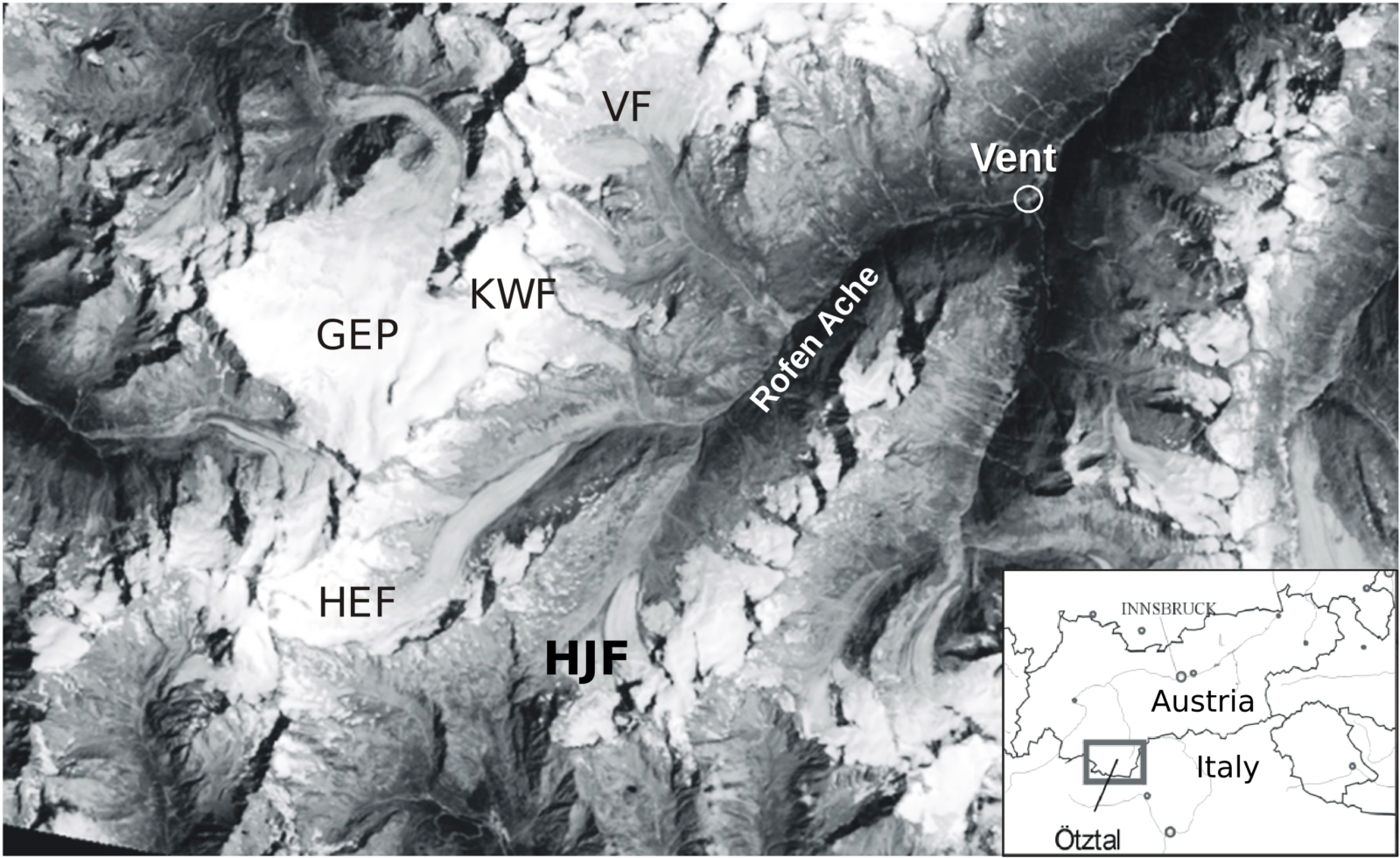

One of the highlights during each summer school is a one-day excursion to the Hochjochferner (Figure 1), a local mountain glacier, and the location of a small glacier skiing resort (one of the first skiing resorts to open in the fall for national teams) and the shooting of part of the EVEREST movie in 2014. But Hochjochferner has been famous in the touristic realm of the Alps for decades already (ferner is the local German dialect for glacier). Being located on the northern side of the main Alpine water divide, Hochjochferner used to start in Italy and flow north across the border to Austria, down-valley towards the Ötztal (see Figure 2). Sheep used to have to cross the glacier every spring to reach their summer feeding grounds and cross the glacier once again in the fall. This “Almabtrieb” often occurred during the summer school’s glacier excursions. Interestingly, this ritual performed by the farmers in the Italian Schnalstal / Val Senales to bring their sheep to the Austrian side of the mountain ridge is a long-inherited right, which goes back way before the formation of national states as we know them today. But nowadays, the sheep have a much easier path: there is no glacier to cross anymore. It has retreated, a lot. Over the 20-year history of the summer school, climate change has left a clear mark on Hochjochferner.

Figure 2 is a typical image used during the Karthaus satellite remote sensing lecture and shows the Ötztal Mountains with the Hochjochferner (HJF) on a Landsat 5 image. The glacier is fed by two upstream catchments, separated by a mountain ridge and the glacier fills the whole valley. Between the two branches is a prominent medial moraine, which originates from that ridge.

Fig.2. Landsat 5 image of the Ötztal Mountains with the Hochjochferner glacier marked as HJF (taken in 16 August 1992). The inset locates the Ötztal Mountains on the border between Austria and Italy. (Other glaciers marked in grey are HF: Hintereisferner, GEP: Gepatschferner, KWF: Kesselwandferner, VF: Vernagtferner.) Courtesy of W. Rack (2008).

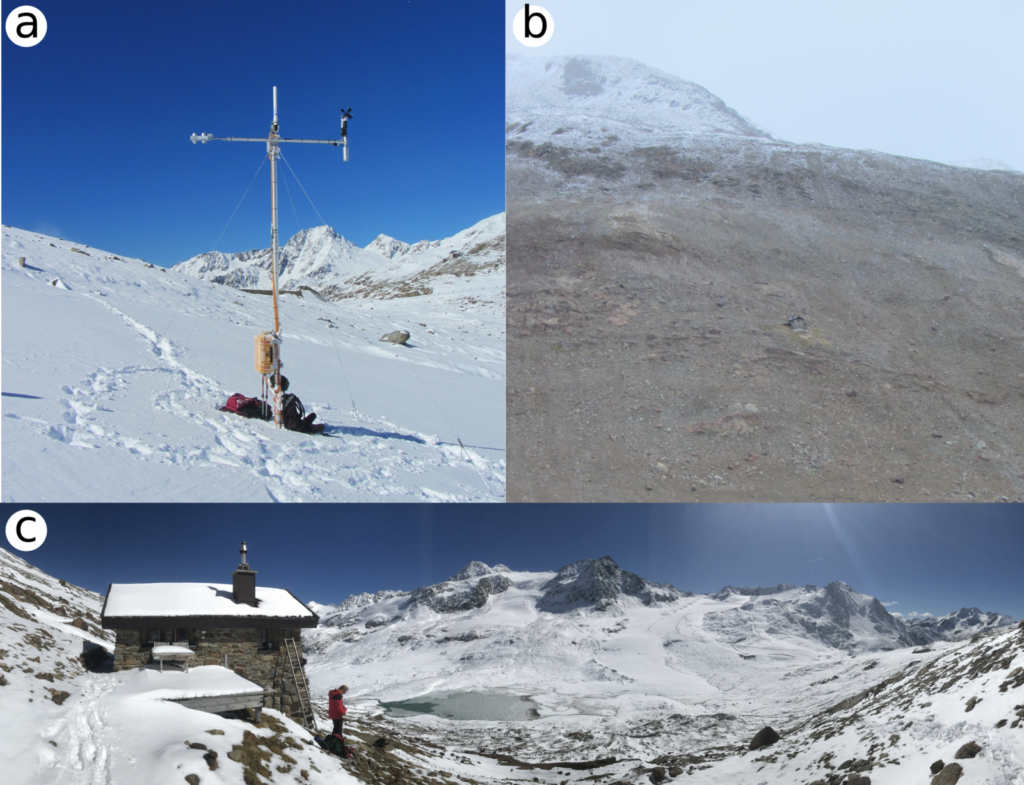

Each generation of Karthaus students has only seen one snapshot in time of the state of the glacier. Only long-term lecturers and those who attended the school themselves as students, have seen how much smaller the glacier has become year after year. One of the excursion stops is by an automatic weather station (AWS) on the glacier operated by the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research Utrecht (IMAU) which was installed in 2013 (Figure 3 a) and replaced an older one. It has been customary to check it once a year during the summer school, to make sure all is working right. However, the strong retreat of the glacier (and therefore thinning of the glacier) forced the dismantling of the AWS in 2018, before the glacier disappeared underneath it.

Also in 2013, a time lapse camera (Figure 3 b&c) was added on the former customs hut (“Zollhaus”), a refuge for customs officers. Interesting tidbit: this hut is a reminder from the time when border control was still in place between Italy and Austria before the Schengen agreement. Today, the customs hut is privately-owned and can be rented for honeymooners or visitors. The camera was taken down in 2018, and the last picture of the glacier was taken by hand in fall 2019.

Fig.3. Photos of a) the weather station on Hochjochferner in September 2017, b) the customs hut as seen from the AWS site in September 2016, and c) panoramic view of the customs hut and Hochjochferner in 2017. Photo credit: O. Eisen and C.Tijm-Reijmer.

The resulting movie (see below) sadly illustrates how Hochjochferner has changed over merely six years. The camera was attached to the customs hut and the images are from September of each year (end of the melt season), starting in 2013. Year 2017 is missing due to early snowfall and malfunctioning of the camera. A white dot marks the location of the AWS on the movie. The only remain of the glacier’s former glory is its cross-cutting medial moraine, still visible today.

https://youtu.be/YtZ8kYvYQ-I

Future perspectives

It is not all bad news for the summer school, as with the glacier dying, new types of glaciological features have developed over time, with glacier retreat being also an interesting glaciological process. The glacier’s rapid retreat left behind a number of geomorphological features, such as small eskers (eskers are long ridges of sediments formed by water action at the base of glaciers). Students can now see in real-time how such features form and how they are related to a glacier’s activity, to the interaction of water and sediments, and of course the evolution of a glacier’s extent.

In the current climate, with 2019 being the hottest year in Europe, and the last decade being – yet again – the warmest decade on record, Hochjochferner continues its demise. The lower part will likely disappear in the next five years, while the upper part might last another decade or so. The 2040s’ generation of students, if the summer school still exists, most likely won’t get to walk on the ice anymore, but will bear witness to the effects of climate change caused by humans.

UPDATE: The movie has been updated to include the 2020 and 2021 images and shows that indeed the lower part of the glacier has almost disappeared.

Further reading:

- The Karthaus summer school: www.projects.science.uu.nl/iceclimate/karthaus

Edited by Marie Cavitte

Olaf Eisen is a Professor of Glaciology at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, and at the University of Bremen, Germany. His research focusses on the application of glaciological and geophysical field observations to understand the properties of ice sheets and glaciers and their interaction with their surrounding environments. He conducted numerous field campaigns in both polar regions and on alpine glaciers. Since 2017, he has been President of the EGU Division on Cryospheric Sciences and Co-Editor in Chief of the journal The Cryosphere. Contact email: oeisen@awi.de

Olaf Eisen is a Professor of Glaciology at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, and at the University of Bremen, Germany. His research focusses on the application of glaciological and geophysical field observations to understand the properties of ice sheets and glaciers and their interaction with their surrounding environments. He conducted numerous field campaigns in both polar regions and on alpine glaciers. Since 2017, he has been President of the EGU Division on Cryospheric Sciences and Co-Editor in Chief of the journal The Cryosphere. Contact email: oeisen@awi.de

Carleen Tijm-Reijmer is an assistant Professor in Polar meteorology, at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research (IMAU), Utrecht University, in the Netherlands. Her research focusses on ice-atmosphere interactions in terms of the surface mass and energy balance through modelling (e.g. energy balance- and regional climate models), and observational techniques (e.g. automatic weather stations). She has participated and (co)organised glacio-meteorological fieldwork in Antarctica, Greenland, Svalbard and the Alps, is co-organiser of the annual Karthaus summer school on Glaciers in the Climate system and is currently deputy president of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) Division on Cryospheric Sciences. Contact email: c.h.tijm-reijmer@uu.nl