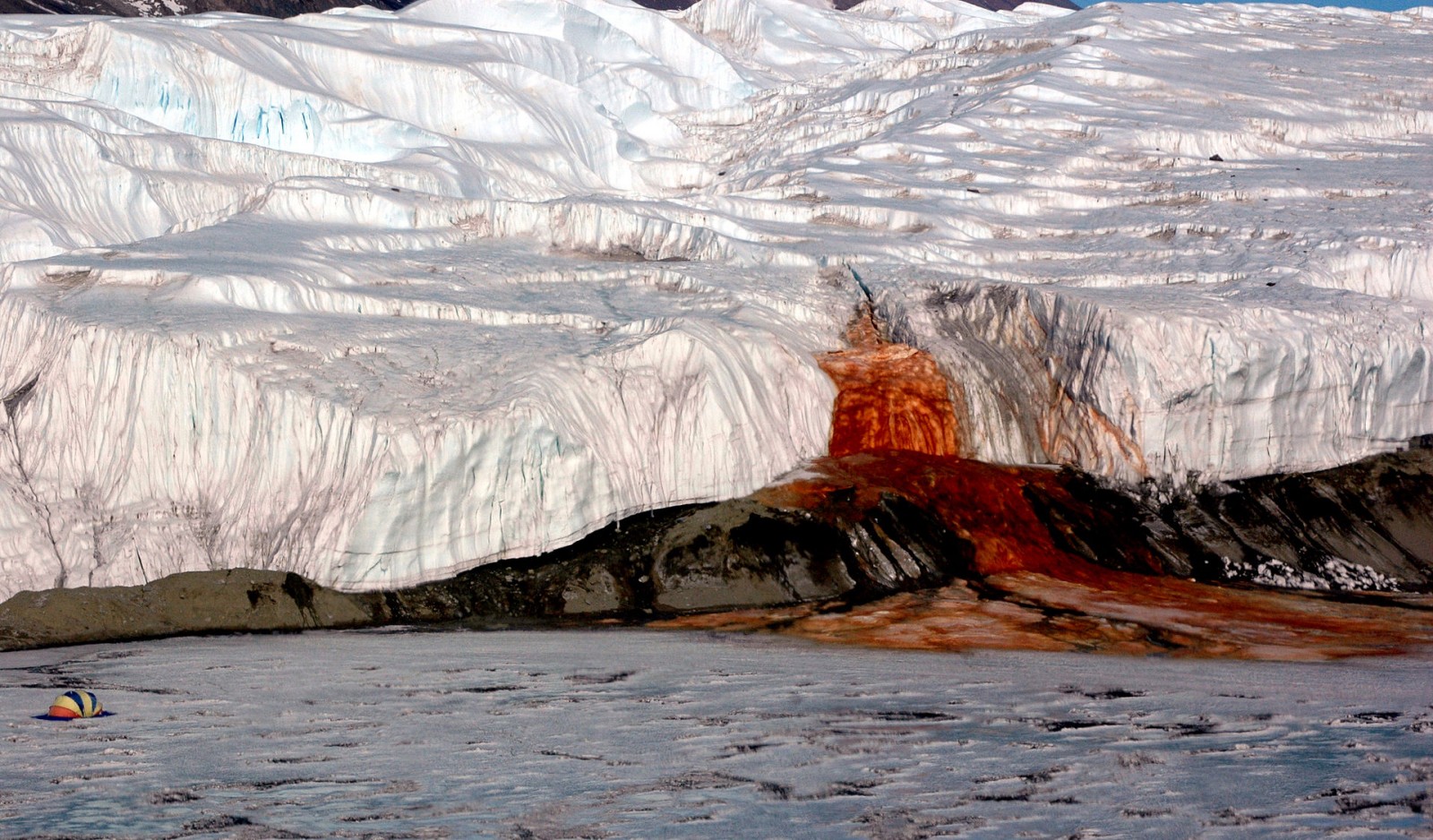

If glaciers could speak, you might imagine them saying – “HELP!” The planet continues to warm and this means glaciers continue to shrink. Our new image of the week shows a glacier that appears to be making this point in a rather dramatic and gruesome way – it appears to be bleeding!

If you went to the snout of Taylor Glacier in Antarctica’s Dry Valley region (see map below) you would witness a bright red waterfall, around 15m high, flowing from the glacier into Lake Bonney. Due to it’s colour, this waterfall has acquired the somewhat graphic name: Blood Falls!

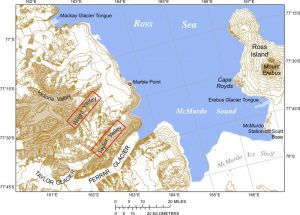

The Dry Valleys

Location of Taylor Glacier in Taylor Valley – one of the Antarctic Dry Valleys. The American McMurdo Research Station is located a short distance away [Credit: USGS via Wikimedia Commons ]

The dry valleys, as the name suggests, are considered one of the driest and most arid places on Earth – which seems like an unusual location for waterfall! The area is completely devoid of animals and complex plants, however, in finding an explanation for the colour of Blood Falls, scientists have also gained an insight into a whole ecosystem hidden beneath the Dry Valley glaciers.

Why is the water red?

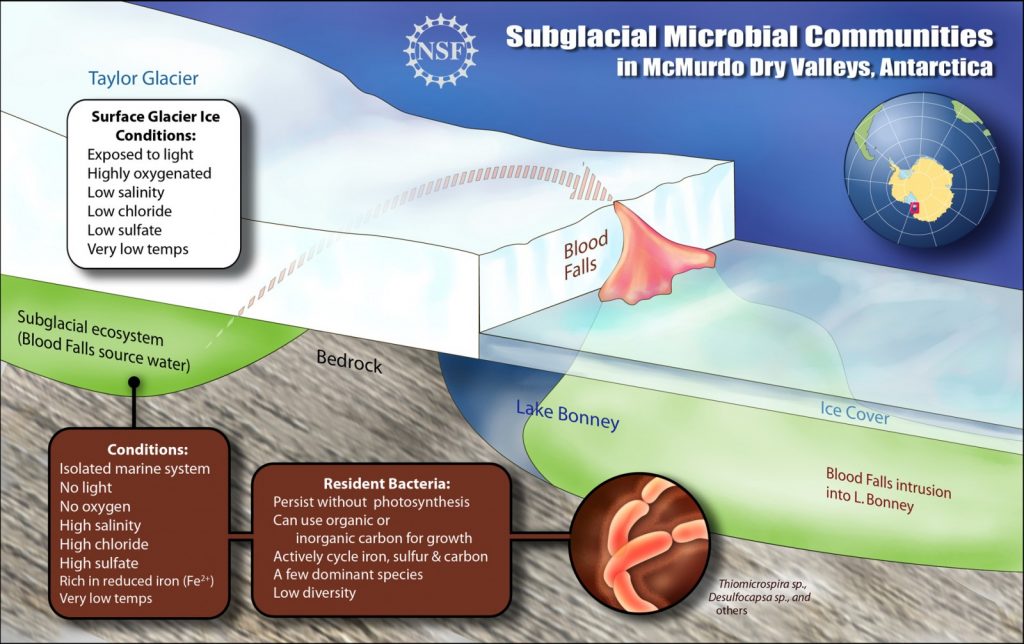

The water that feeds Blood Falls is salty and rich in iron. This water is forced out from underneath the glacier by the pressure of the overlying ice (see schematic below) and as it emerges the iron in the water comes into contact with oxygen causing it to rust (oxidise) and turn the water red. But why is this water so salty and iron-rich in the first place? The story of how this unusual water came to be starts around five million years ago…

At this time, it is thought that the dry valleys were submerged beneath the ocean as part of a system of fjords (Mikucki et al., 2015). Subsequent uplift of this land and climatic cooling causing a drop in sea level left some of this salty ocean water isolated as a lake. Around 1.5 million – 2 million years ago a glacier started to form on top of this lake. The ice cut the lake off from the atmosphere and caused the lake water to become even more salty by the process of cryoconcentration (lake water in contact with the glacier ice is frozen, the salt is left behind in the lake increasing the concentration). Iron was introduced into the water from the bedrock beneath the lake, which was ground up as the ice moved over the top of it. There was also something else in this ancient sea water, that surprised scientists when they began to analyse the water from Blood Falls – microbes!

A schematic cross-section of Blood Falls showing how microbial communities survive in this hostile environment [Credit: Zina Deretsky, NSF ]

Life in the lake – Microbes

When it was covered in ice, this subglacial lake was very cold and cut off from the out side world – meaning no sun light and oxygen, which are normally essential for microbes to survive. However, the microbes in this lake are thought to have adapted to survive using sulphates and iron in the water (Mikucki et al., 2009). This strange ecosystem is surviving in extreme conditions and shows how adaptable microbes can be. An area once thought to be too inhospitable to support much life has been shown to be much more “lively” than first thought – sparking up ideas about lifeforms in other inhospitable environments, such as Mars.

Further Reading

- Mikucki et al., 2015: “Deep groundwater and potential subsurface habitats beneath an Antarctic dry valley”

- Mikucki et al., 2009: “A Contemporary Microbially Maintained Subglacial Ferrous “Ocean”

- NSF Press Release: “Unusual Antarctic Microbes Live Life on a Previously Unsuspected Edge”

- Smithsonian Magazine: “Antarctica’s Blood Red Waterfall”

Edited by Sophie Berger