The Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition (RSSSE) is a free public event 4-10th July 2016 in London. This is a yearly event that is made up of 22 exhibits, selected in a competitive process, featuring cutting edge science and research undertaken right now across the UK. The scientists will be on their stands ready to share discoveries, show you amazing technologies and with hands-on interactive activities for everyone! The Royal Society has historic origins – going back to the 1660s and today it is the UK’s national science academy working to promote, and support excellence in science and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. If you can get yourself down to London this week then it is definitely worth a look!

What is there to see?

This year there are a number of ice-related exhibits. The “4D science” exhibit uses X-ray computer tomography to look inside ice cream and the “Explosive Earth” exhibit showcases ice-volcano interactions in Iceland using earthquakes. The Summer Science Exhibition yearly attracts around 12,000 visitors. This is a unique opportunity to meet cutting edge scientists, discover their research and try out fun and engaging activities for yourself.

Left: The Explosive Earth presented by the Cambridge University Volcano Seismology Group. Right: 4D Science: Diamond Light Source, University of Manchester and University of Liverpool – Looking inside materials through time. Photo Credit: Jenny Woods

Explosive Earth!

The Explosive Earth exhibit has been put together by the Cambridge Volcano Seismology group. They explore many applications of volcano seismology, from what we can learn about movement of molten rock (magma at more than 1000°C) in the Earth’s crust and rift zone dynamics, to the very structure of the earth itself. They currently focus their research in central Iceland where they operate an extensive seismic network in and around some very active volcanoes, many of which are under Europe’s largest ice cap Vatnajökull. The seismic network detects tiny earthquakes caused by the movement of magma beneath the surface, which often occurs under volcanoes prior to eruption. By studying these seismic events, they hope to be able to predict volcanic activity better in the future. Their exhibit at RSSSE showcases current research in this explosive field of volcano seismology.

Eyjafjallajökull – 2010: an explosive eruption that disrupted air traffic

The 2010 eruption at Eyjafjallajökull (image at the top of the page) occurred beneath a glacier, which caused a highly explosive eruption. When hot magma comes into contact with ice the magma cools and contracts and the ice turns to steam and rapidly expands. This shatters the solidifying magma and produces ash. The explosivity of the interaction, and the pressure of all the rising magma underground, blows the mixture of ash, volcanic gases and steam high into the air, creating an eruptive plume. The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption produced an ash plume that reached up to 10 km (35,000 feet). The fine ash was then carried 1000’s of km by the wind towards Europe where it grounded over 100,000 flights.

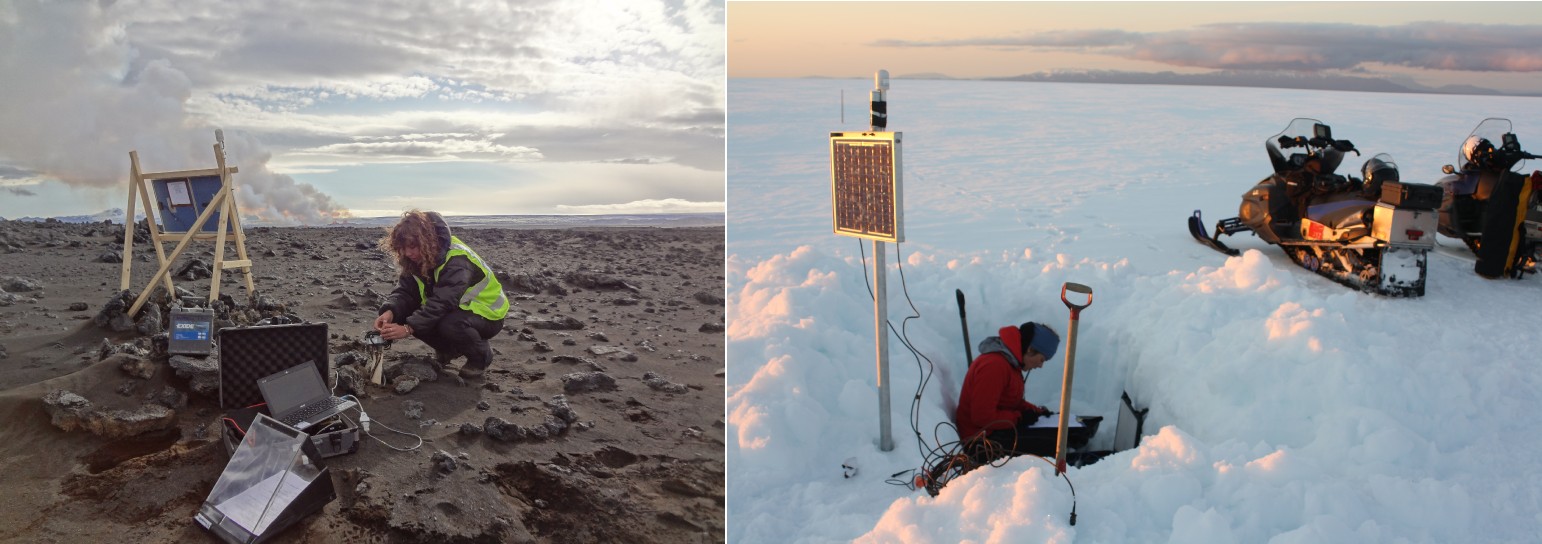

Installing seismometers in a variety of locations around Iceland to monitor tiny earthquakes from magma movement under the surface. Photo Credits – Left: Rob Green, Right: Ágúst Þór Gunnlaugsson

Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun – 2014: a gentle eruption that affected air quality

In 2014 a completely different kind of eruption happened in central Iceland, also originating from a volcano under the ice. Magma flowed underground from Bárðarbunga volcano, beneath Vatnajökull ice cap, fracturing a pathway so far from the volcano that when it erupted there was no ice at the surface. Without the magma-ice interaction, the eruption was comparatively gentle and the molten rock simply fountained out of the ground, reaching heights of over 150 m. No ash was produced, only steam and sulphur-dioxide. The amount of magma erupted was much greater than in 2010 (an order of magnitude higher), but there was no impact on air travel because there was no ash plume. The Explosive Earth team are investigating the 30,000 earthquakes that led up to this spectacular six-month eruption in Iceland, to try and find out more about what happened and why. The earthquakes tracked the progress of the molten rock as it moved underground, away from Bárðarbunga volcano to the eventual eruption site at Holuhraun, 46 km away.

The fountains of lava accompanied by clouds of steam and sulphur-dioxide. The magma flowed 46 km underground from Bárðarbunga volcano to the eventual eruption site at Holuhraun, where it erupted continuously for 6 months. Photo Credit: Tobias Löfstrand

Cambridge Volcano seismology group in front of the fissure eruption on the first day of the 2014-15 Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun eruption. Photo Credit: Thorbjörg Águstsdóttir

What can monitoring these earthquakes tell us?

Monitoring volcanic regions in Iceland is important because eruptions are frequent and have wide-range impacts:

-

Explosive eruptions under ice can cause rapid and destructive flooding of inhabited areas downstream, and can propel huge ash clouds into the atmosphere, disrupting air travel around the globe.

-

Gentle eruptions, producing large lava flows, can release millions of tones of harmful gases, affecting the local population and in some cases the global climate.

Studying earthquakes helps to understand the physical processes that occur in volcanic systems, such as how molten rock intrudes through the Earth’s crust and how the centre of a volcano collapses. The more we understand about the behaviour of these systems, the better we can forecast eruptions.

“Explosive Earth” exhibits earthquakes and eruptions in Iceland in a fun interactive way. You can find out more details of the science behind why and how these eruptions happen and how it is possible to monitor volcanic activity in Iceland using earthquakes. As a taster of what you can see, try entering your postcode into their lava flow game to see how big the Holuhraun lava flow is and how far it travelled underground prior to erupting. Other interactive activities include making your own earthquake and testing your reaction times with an earthquake location game.

(Edited by Emma Smith and Sophie Berger)

Thorbjörg Águstsdóttir (Tobba) is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge studying volcano seismology. Her research focuses on the seismicity accompanying the 2014 Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun intrusion and the co- and post-eruptive activity. She tweets as @fencingtobba, for more information about her work see her website.

Thorbjörg Águstsdóttir (Tobba) is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge studying volcano seismology. Her research focuses on the seismicity accompanying the 2014 Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun intrusion and the co- and post-eruptive activity. She tweets as @fencingtobba, for more information about her work see her website.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Ice on Fire (Part 2)