Ekbal Hussain is a PhD student at the University of Leeds, and helps to coordinate our group up there. He is a passionate advocate for disaster risk reduction and today writes about the relationship between corruption and earthquake fatalities.

Ekbal Hussain is a PhD student at the University of Leeds, and helps to coordinate our group up there. He is a passionate advocate for disaster risk reduction and today writes about the relationship between corruption and earthquake fatalities.

It is no profound statement to say that earthquakes are extremely dangerous natural events and are responsible for tens of thousands of deaths annually. What is more contentious is my belief that no one needs to die from earthquakes at all.

Let me explain myself; most deaths from earthquakes are a result of the collapse of buildings and other man made structures such as bridges. We have the technical engineering expertise to build structures that withstand ground shaking during earthquakes.

Every year our understanding of the earthquake process increases but many important gaps remain, particularly on issues such as timing and location of future earthquakes. However, as Charles Richter mentions in his retirement speech: “For public safety we don’t need prediction, earthquake risk can be removed, almost completely, by proper building construction and regulation.” (1970)

So if we know the cause of earthquake deaths and what we need to do to minimise losses why do people still die in them? The answer to this question is by no means simple. Many factors contribute to losses during these events: insufficient knowledge of where all the earthquake generating faults are, cultural practices, uncertainties in hazard maps, poverty and poor building practices among others.

For this post I’d like to focus on the role of corruption in the building industry. The global construction industry was worth $8.7 trillion in 2012[1] and this is recognised to be the most corrupt segment of the global economy [2].

Spontaneous factory collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh resulted in 1129 deaths in 2013. Source: Wikimedia Commons – Rijans

Corruption takes the form of using inadequate and/or insufficient building materials, bribes to inspectors and civil authorities, substandard assembly methods and the inappropriate siting of buildings. Spontaneous building collapses even without earthquakes, such as the Saver factory collapse in Bangladesh last year which killed 1129 people, are a stark reminder of the consequences of construction oversight and a terrifying view into what could happen if there is an earthquake in these regions.

The 1999 Izmit earthquake (magnitude 7.4) in Turkey resulted in around 18,000 deaths. It was later shown that half of all the structures within the damage zone had failed to comply with building regulations [2].

“The structural integrity of a building is no stronger than the social integrity of the builder.“

–Nicholas Ambraseys & Roger Bilham–

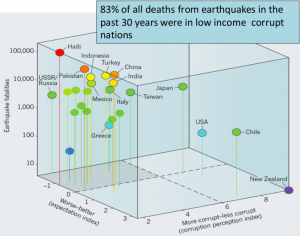

Nicholas Ambraseys and Roger Bilham calculated that almost 83% of all deaths from building collapse in earthquakes in the last 3 decades occurred in countries that are poor and anomalously corrupt [3].

3D plot of earthquake deaths with corruption perception index and expectation index, i.e. are the countries more or less corrupt than expected. Source: Ambraseys, N. & Bilham, R., 2011

Corruption by itself is dangerous but when combined with poverty, it is disastrous. Corruption, poverty and ignorance essentially become indistinguishable for low income countries. And even if corrupt practices are eliminated these countries will have inherited a building stock that is poor quality and prone to failure in the next earthquake.

However, it’s not all bad news. There are some great examples of how reconstruction can take place under correct management and regulations to improve resilience to earthquakes. For example, in 2012 the Turkish government passed the Law on the Regeneration of Areas Under Disaster Risk. Under these new guidelines all buildings that are not up to current earthquake risk standards will be demolished and rebuilt. As a result 6.5 million high risk houses will be demolished over the next two decades [4].

The reconstruction of the Macedonian capital of Skopje after it was destroyed in an earthquake in 1963 is another great example. Not only was the entire infrastructure rebuilt to be earthquake-resistant, the city planning also ensured that the river Vardar was routed in order to control future flooding [5].

Achievements on this scale require strong governance and management, and transparent sectoral and local administration. With the rapid growth of cities into so-called megacities (>10 million population) often in high earthquake risk regions this is even more important. We have yet to have an earthquake that has killed a million people. But at the rate these cities are growing under limited to no management such an event might not be too far in the future.

References:

[1] Global Construction 2025: A Global Forecast for the construction industry to 2025 (2013)

[2] Global Construction 2020: A Global Forecast for the construction industry over the next decade to 2020. (2010)

[3] Ambraseys, N. & Bilham, R., Corruption Kills, 2011

[4] http://www.portturkey.com/real-estate/5627-65-million-houses-to-be-demolished-in-turkey

[5] Vladimir B. Ladinski, Post 1963 Skopje earthquake reconstruction: Long term effects, 2010

Further Reading

http://www.transparency.org.uk

If you have any questions for Ekbal, or want to comment on this blog – don’t forget you can do so using the box below.

Simon Redfern

Nice piece – I heard JJ say that Tehran was the most vulnerably mega-city on an active fault, for many of the reasons above. Any view?

Ekbal Hussain

Hi Simon.

Yes Tehran and Istanbul are in very similar situations in that they are very very large cities (populations exceeding 13 million) situated close to large active faults.

Both of these cities have grown extremely rapidly in a time that is much shorter than the average earthquake repeat time on the faults. For example the last time Istanbul was destroyed in an earthquake was in 1509 and since then the population has grown from tens of thousands to around 13 million. A similar situation exists for Tehran which was last destroyed in 1830.

Both cities are still growing at an alarming uncontrolled rate.

Istanbul and Tehran are two cities (along with a few in China) that are candidates for the so-called “million death quake”.

It is difficult to assess which is the “most vulnerable” as an earthquake in either location will result in widespread destruction and loss of lives.

One thing my post didn’t talk about is “why” these people are corrupt in the first place. That’s something I’m quite interested in and something I’ve had personal experience of during my travels in Bangladesh. Perhaps that’s a topic for another blog post 🙂

Joel Gill

Ekbal, Great post! I wanted to ask about the 2012 law being passed by the Turkish Government and how optimistic you are that homes will be built back better?

It’s one thing to assess which homes are vulnerable and order them to be rebuilt, but another to ensure the same corruption that caused some of them to be built to an inadequate standard in the first place is not repeated. I’m assuming that there were building codes in place before 2012 – but that these weren’t followed in many cases?

I guess I wonder how much a new law ordering better building will impact levels of corruption, without targeting this corruption and the reasons for it as well. I think more discussion on the ‘why’ and how we tackle this would be great!

Navneet Yadav

Hi Ekbal,

Your article is worth reading and provides a great deal of understanding about the linkage between the construction and corruption. I am based in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh and have been observing drastic changes in the built environment of the towns/cities in the Indian Himalayan region. On the basis of my experiences, I wish to add that lack of scientific development planning, pathetic building regulation and improper enforcement of the existing building codes in Indian sub-continent has already rendered some of the cities as future graveyards. Even worse is the politically-inspired regularization of illegal constructions which guarantees of a good vote bank for some political parties. Rest of the evil lies in the lethargic approach of the planners, architects, engineers etc. who, for some reasons, do not consider safe construction as their prime responsibility. I believe that there still is hope for such countries in the form of civic movements based on the corruption-free good governance and transparency.

Ekbal Hussain

Hi Joel,

That’s a great question and one I purposely didn’t address in my post. In theory the law is a good idea. It’s estimated to generate about USD 500 billion in construction industry over the next decade or so. However there is no clear mechanism in place to manage the rebuilding of towns and buildings, at least not one that I am aware of.

In fact there is already quite a bit of unrest concerning inadequate provisions for the rebuilding of houses. There are rumours that the select committee are deciding that buildings are unsafe and ordering it demolished but not giving the support to help the rebuild it.

I really don’t know what can be done to prevent this type of corruption. There are some ideas of making a system (perhaps a mobile app) where the local communities can report to the civil authorities if they do not get their due support but that’s just an idea at the moment. Such a system would massively improve transparency in the money traffic between the source of the money and the people that are meant to eventually get it.

All we can hope for at the moment is that over the many millions of houses that will be ordered rebuilt a fraction of them will be built properly.

Joel Gill

Thanks Ekbal, interesting indeed! I know a lot of NGOs are focusing on anti-corruption campaigns at the moment – linked to improving business, transparency (in extractive industries) and tax revenues. It would be great to raise their attention to the importance of corruption and DRR, so as to see a more integrated approach and perhaps utilise their campaigning networks. Perhaps I will try and raise this when I next have an opportunity.

Ekbal Hussain

Hi Navneet

You have hit the nail on the head. So much of what you’ve said is repeated in countries around the world. I do believe some progress can be made with increased awareness of the consequences of construction oversight, i.e. tackling ignorance. But the larger issue of corruption is a much harder problem to solve. And one that, like you mentioned, can only be addressed with good governance and complete transparency. Basically India needs more people like you!!!

Joel,

That’s a great idea and one I would highly encourage we bring to the limelight. We can throw as much money as we want into DRR but if that money never gets to its intended target then it will have been a pointless venture. I personally don’t believe we can be a truly resilient society with corruption. It’s a choice between a corrupt society or a resilient one.

Ekbal