Rainfall-related geohazards in Brazil’s poorer, mountainous city margins could be mitigated using better urban planning and communication. Our own Brazilian blogger Bárbara Zambelli Azevedo explores the problem and possible solutions.

I come from Brazil, a country well-known for its beautiful landscapes, football and carnival. Ok, some stereotypes are true, indeed.

Situated in the middle of the South American tectonic plate and away from geohazards such as earthquakes, volcanoes and tsunamis, this tropical country may seem like paradise to some. However, we are not completely safe from geohazards.

Every year during the summer, which is a heavy rain season, many lives are lost, and people are displaced by floods, landslides and mudslides all over the country. I want to give a particular focus on the state of Rio de Janeiro, where a summer storm killed at least 6 people on the 6th of February this year. I should mention that it was not an isolated event at all.

The situation of the state of Rio de Janeiro is complicated, and its analysis should take into consideration the geomorphology of the area, its climate and – importantly – urban planning.

According to the Brazilian Geological Survey, the bedrock in the area is composed mainly of igneous and metamorphic rocks, and the relief is characterised by steep mountain slopes over 2,000 m, alternated with sedimentary basins.

In 2011 floods, landslides and mudlslides resulted in 903 deaths and over 2,900 people had their homes destroyed

These mountains are a part of a major structure named Serra do Mar (Sea Ridge), a 1,500 km long system of mountain ranges and escarpments parallel to the Atlantic Ocean, running from Rio de Janeiro State until Santa Catarina, in the south of Brazil. Geomorphological features seen today started to form during the opening of the Atlantic Ocean during the Cretaceous, were consolidated throughout the Tertiary and still are modified by erosional and sedimentary events.

The climate is described as tropical in coastal areas such as Rio de Janeiro City and Angra dos Reis. It is warm and humid all year round, with a mean temperature around 23°C and an average annual precipitation of 1,300 mm. The rain season occurs in the summer (Dec-Mar) when 45% of precipitation falls.

In mountainous areas such as Nova Friburgo and Teresópolis, the climate is characterised as temperate. Temperatures are milder at an annual mean of 18°C and the average annual rainfall is 1700 mm, with 59% falling in the summer months of December to March. Therefore, extreme rainfall events are not rare, and they are usually associated with floods and landslides.

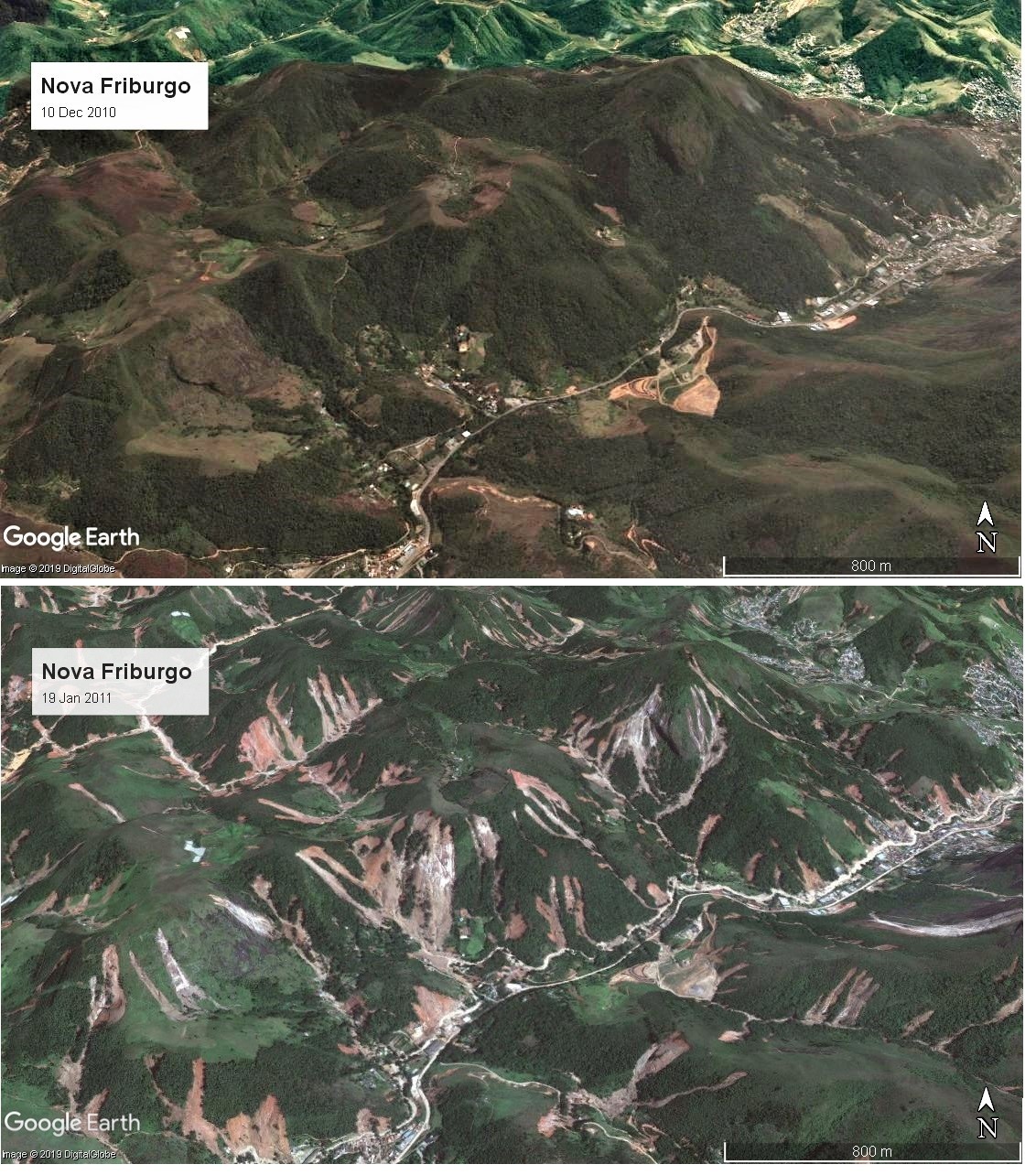

The worst weather-related natural hazard-induced disaster in Brazil happened in January 2011, when it rained 166 mm in a 24 hour period in the Serra dos Órgãos region, which is a local denomination of Serra do Mar. Six cities were affected by floods, landslides and mudslides: Teresópolis, Petrópolis, Nova Friburgo, Bom Jardim, Sumidouro and São José do Vale do Rio Preto. These flows resulted in 903 deaths and over 2,900 people had their homes destroyed.

A year earlier the state of Rio had been the scene of another tragedy. It was New Year’s Eve and the city of Angra dos Reis was full of tourists. After intense rainfall, many mudslides were triggered and left at least 44 people dead. Such events repeat themselves every year.

Satellite imagery of the 2011 mudslides in Nova Friburgo – before and after. Via Google Earth, collected in 2019.

Just like Rio, most Brazilian cities lack urban planning and settlements are segregated socio-economically. Usually an impoverished population is pushed to marginalised areas of cities, which are usually steep and mountainous areas where the risk of landslides is higher.

In this article geologist and former president of the Institute of Technological Research of São Paulo Álvaro Santos states that only few Brazilian geohazards are triggered exclusively by nature.

In fact, most of our geological and hydrological issues are, somehow, led by poor land-use management, both in cities and in the countryside. Santos also explains that tragedies related to rainfall are usually caused by a lack of land-use planning and housing, and inefficient government communication.

We must learn from our own history and examples from other places like Indian Chennai and Tamil Nadu to tackle the challenge elevated hazard risk in city margins. A good starting point is raising the awareness of the population living in high-risk areas by using geoscience education and science communication.

Geoprevention aims to raise the awareness of the local community about geotechnical and environmental risks such as floods, landslides, infiltration, river erosion and sedimentation and waste disposal

We have a good example from the city of Curitiba, where students from the Federal University of Paraná developed a project titled GeoPrevention. This project aims to raise the awareness of the local community about geotechnical and environmental risks such as floods, landslides, infiltration, river erosion and sedimentation and waste disposal. The students use didactic material like folders, manuals, booklets and provide mini-courses and lectures about these topics with a playful character that is easily understood.

This initiative is important because it provides an interdisciplinary dialogue between a university and civil society, in particular, the population affected by those geohazards, to recognise and avoid them at the individual level.

At a higher level, we need governments and policy-makers to take action on effective urban planning and risk management, and invest more in the prevention of rainfall-related geohazards than on their remediation.

In addition, the active participation of civil society and the private sector is crucial to building resilient societies. Technological innovations such as the internet of things and dashboards should also be used to improve disaster prediction and population warning.

The city of Rio de Janeiro has two big data operation centres, the Operation Centre and Integrated Centre of Command and Control, both launched before World Cup which granted Rio the title of “World Smart City” in 2013.

The centres improved disaster management by mapping areas with high risk of flood-related landslides and implementing a critical early warning and evacuation system for Rio’s favelas. However, according to this article, they have failed at “go[ing] beyond high-tech marketing rhetoric and help[ing] real people living in the city”.

Even though it is very complicated and takes time to solve the problem of rainfall-related hazard risk in city margins, it must start sometime: why not now?!