In a couple of days, on 22 February, we will mark a major milestone in space history: 40 years since the launch of the first Swedish Viking satellite, when an Ariane rocket from Kourou in French-occupied Guiana launched on 22 February 1986! While the general public might hear the word Viking and picture longboats, heavy axes, and a level of beard maintenance that borders on the professional, space scientists see something else entirely. In the world of science, Viking represents a series of daring raids into the secrets of the solar system for, guess what? Data. Specifically data regarding plasma, the fourth state of matter, as ubiquitous as it is frustratingly difficult to pin down.

From the rust-colored plains of Mars to the shimmering curtains of the Northern Lights, the Viking legacy represents the moment plasma physics moved from the chalkboard to the stars. It was the era when we stopped guessing how the sun interacts with planets and started measuring the mosh pit of charged particles for ourselves.

Understanding plasma

To appreciate what the Viking missions achieved, we first have to rescue the definition of plasma from the back of a high school textbook.

Most people are taught that plasma is ionised gas. That description is technically true, but it’s also incredibly bland. In reality, plasma is a charged, collective, and highly reactive, let’s say, soup of particles! Because the electrons have been stripped away from their atoms, the resulting mix becomes hyper-sensitive to electric and magnetic fields. Plasma doesn’t just flow; it also twists, pinches, and beams. It fills 99% of the visible universe, from the heart of stars to the thin void between galaxies. It is basically the universe’s most dramatic state of matter: always charged, always in a group project with magnetic fields, and never quite where the diagrams say it should be. To truly understand it, we had to go where it lives.

Mars, but make it ionospheric

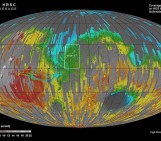

While the 1976 Viking 1 and 2 missions are legendary for their search for Martian life, they also carried a hero for physicists: the Retarding Potential Analyzer (RPA). This sophisticated bonk detector used electrical grids to measure ions in the Martian ionosphere. This provided the first ever in-situ look at how solar radiation transforms another planet’s atmosphere into plasma. The data revealed a surprisingly chaotic ionospheric mosh pit, where low-energy electron levels skyrocketed during descent, and the boundary with the solar wind was a turbulent, messy smear rather than the crisp line predicted by textbooks. When it proved that space refuses to behave like a neat diagram, Viking successfully turned abstract plasma equations into a gritty, thrilling reality.

From longboats to low Earth orbit

Launched in 1986, the Swedish Viking satellite was indeed Sweden’s first satellite. While it shared a name with the NASA planetary landers, this Viking orbited Earth and never landed anywhere. Its eyes were turned toward a different plasma phenomenon: the Aurora Borealis.

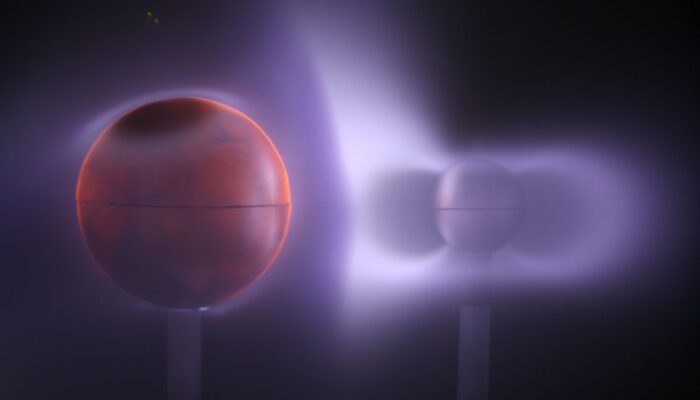

To the average observer, the Northern Lights offer a silent, poetic, dance across polar skies. To plasma physicists, however, the aurora is anything but gentle! It’s actually a powerful natural particle accelerator. These shimmering curtains are visual proof of Earth’s magnetic field lines channeling high-energy particles into our atmosphere, where they slam into gas molecules and trigger cascades of light.

Viking was launched into a highly elliptical orbit specifically designed to sample the auroral acceleration region, positioned roughly 1 to 2 Earth radii above the surface. This altitude was a strategic sweet spot that previous satellites had either skimmed beneath or sailed well above, leaving a critical observational gap.

Equipped with a sophisticated instrument suite, including the V3 particle spectrometer, Viking spent 444 days embedded in the electromagnetic maelstrom of the auroral zone. The mission was a massive international plasma expedition and drew scientists from Canada, Denmark, France, Norway, the United States, and West Germany into a collaborative hunt for understanding.

Viking’s daily routine involved flying through shock structures, wave bursts, and particle beams. Imagine piloting an extremely sturdy, extraordinarily expensive thermometer directly through a thunderstorm, except the storm consists of charged particles and writhing magnetic fields, and the lightning never stops. That was Viking’s everyday commute. During its mission, Viking detected auroral kilometric radiation (AKR) and, by crossing these radiation source regions, made measurements showing that auroral kilometric radiation is generated within field-aligned auroral acceleration structures linked to electron precipitation and discrete auroral arcs. Yet, what I find most remarkable, is that Viking also captured some of the first high-resolution images of the aurora from above. This showed, in detail, the structures that are normally invisible from the ground, therefore developing human understanding of these celestial storms.

Why do we bother the plasma?

It is tempting to treat all this as a niche saga of “‘Nerds Bother Plasma” film at 11′. But the Viking missions did something structurally important: they moved plasma physics from an Earth-centric theory into a multi-world discipline.

When we take measurements at Mars, a planet with no global magnetic field, and compare them to Earth (a planet with a very strong one!) we create Comparative Magnetospheric Science. These data provide the benchmarks for:

-

Understanding how the solar wind strips the atmosphere away from a planet (explaining why Mars went from wet and blue to dry and red).

-

How different magnetic environments modulate a planet’s long-term health.

-

Learning how energy is rearranged in the vast, magnetised weather of the solar system.

Final reflections

Forty years later, the Viking legacy reminds us that the space between planets is, in simple words, a mosh pit. It’s a turbulent, electric, and magnetic sea that connects every world in the solar system. The Viking missions made it possible to stop guessing and start measuring how that drama actually plays out. They showed us that whether you’re at the poles of Earth or the deserts of Mars, the universe is always plugged in. Plasma might be difficult to study, but as the Vikings proved, if you’re brave enough to sail into the storm with a well-calibrated bonk detector, the secrets you find are worth their weight in gold.