Happy International Soil Day (5 December)! Today, we’re celebrating the incredible capacity of soil organic carbon (SOC) to fight climate change. But hold the celebratory cake! A paper in the journal SOIL by Raza et al. (2025) has exposed an unexpected scientific blind spot, and it’s a bit surprising! The paper, titled “Missing the input: the underrepresentation of plant physiology in global soil carbon research,” reveals that for over a century, the vast majority of soil carbon research has been acting like a detective investigating a crime scene, but completely forgetting to interview the primary witness: the plant.

You can’t have soil organic carbon without the carbon fixer

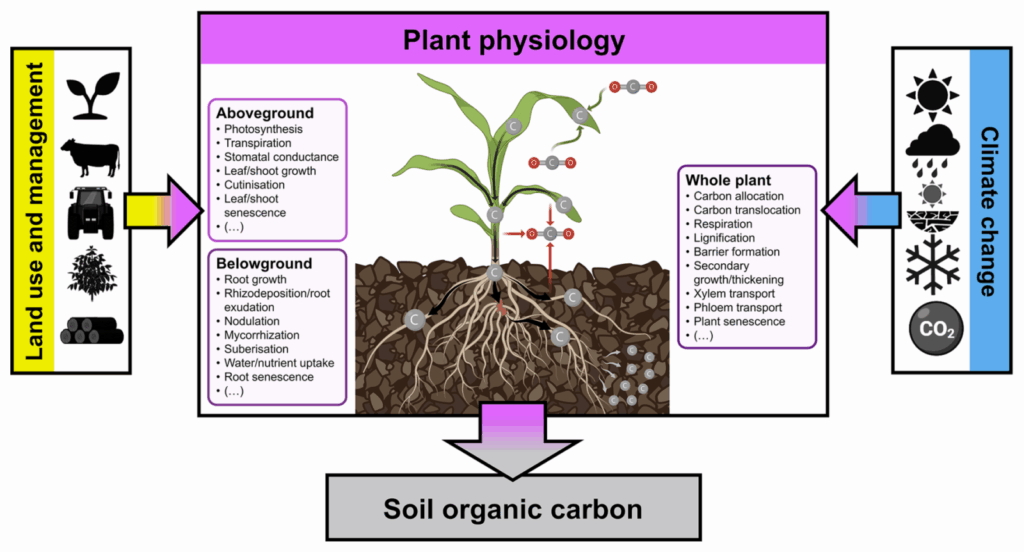

It seems obvious, right? Soil carbon comes from plants. Plants pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis and place that carbon into the soil either as decaying litter or, more dynamically, as rhizodeposits; the root exudates, and the sloughed-off cells carried by the process essentially feed the soil microbiome. Think of it like a restaurant: the soil is the final dish, but the plant is the kitchen, the chef, and the delivery service. The processes within the plant, like deciding whether to send more carbon to the roots (allocation) or what kind of tough organic compounds to make (tissue quality), are the secret recipe for the quality and quantity of soil organic carbon.

Yet, when scientists study how climate change or different farming methods affect soil organic carbon, they have traditionally not included the step of measuring how the plant itself responds.

Scientific silos led to a century of absent data

Raza and their colleagues ran a bibliometric analysis on over 55,000 papers on soil organic carbon published since 1904. The results are astonishing:

- Less than 10% of all peer-reviewed Soil Organic Carbon research actually included the relevant plant physiological processes.

- Even more baffling, in research specifically focused on the impact of climate change or land use and management, the very factors that force plants to change their carbon behavior, the ratio barely budged. Over 90% of those papers still excluded the plant.

As the authors put it:

“These findings show that our understanding of both soil carbon dynamics and the carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial ecosystems is largely built on research that neglects the fundamental processes underlying organic carbon inputs.”

The implications of this paper are striking for our chance to continue to improve the accuracy of soil organic carbon models – it’s like we have been studying a water faucet’s pressure changes without looking at the valve. This scientific separation, perhaps coming from the division of soil and plant sciences decades ago, has left us with an incomplete picture of Earth’s carbon budget.

Conceptual schematic depicting the central role of plants in soil carbon dynamics. Carbon fluxes from the atmosphere into the soil underlying the quantity and quality of soil organic carbon inputs are driven by a suite of plant physiological processes. These physiological processes and their responses to alterations in land use and management or climatic conditions are therefore key to the current and future potential for soil carbon sequestration. Some elements were created with BioRender.com.

Why interdisciplinary collaboration matters

According to the authors of the paper, plant scientists, including geneticists, physiologists, and ecologists, must become an active and integral part of the global soil organic carbon research community. Otherwise, the environmental and genetic drivers, a critical and integral part of this process, will remain a blind spot in humanity’s understanding of the capacity for soil carbon sequestration. Therefore, it is important for the global scientific community, including researchers and funding agencies, to recognise the pivotal role of plant physiology in shaping soil carbon dynamics. Without this recognition, our understanding of soil carbon sequestration potential across diverse terrestrial ecosystems will remain incomplete.

Achieving accurate modelling and prediction of soil carbon dynamics, through empirical, mechanistic, or geostatistical approaches, is thus dependent on sustained investment in long-term data collection across appropriate spatial and temporal scales, which is essential for quantifying the effects of climatic conditions and land use on key plant physiological processes. These models are indispensable for extrapolating interactions across diverse ecosystems and understanding the resulting impacts on soil carbon, but their development requires improved funding mechanisms that facilitate collaboration among inter- and multi-disciplinary groups of scientists, researchers, industry, and stakeholders; only through these continued and unified efforts can we develop the understanding necessary to inform and implement effective policies for supporting and enhancing global soil carbon sequestration. The paper calls for enhanced efforts that improve funding, which, for instance, enable long-term studies that use cutting-edge tools like isotope tracing combined with 3D imaging to track carbon’s journey from the leaf, down the root, and into the soil. It means making the measurement of root growth and rhizodeposition a standard part of soil surveys, perhaps even using drones and satellites to monitor plant health at scale.

Finally, to make a true difference, the authors state that interdisciplinarity needs to be better supported by funding requirements – abandoning the restrictive disciplinary silos of the past. By launching new grant opportunities and research incubators that mandate the participation of two or more distinct disciplines for eligibility, funding bodies can practically and efficiently support the collaboration of plant physiologists and soil scientists. It is only through the implementation of such structural changes that we can quickly close this century-old knowledge gap and develop the models we need to inform successful global soil carbon sequestration policies.