Reading GeoLog when you should be working? We are all guilty of a little procrastination, but, sometimes, the parallels between science and the games we play to postpone the next write-up are closer than you’d think. Victor Archambault, a scientist from US Radar, reveals how playing Minesweeper mimics the way geoscientists analyse data in the field…

We have all played the infamous Minesweeper that comes with our computer, but few realise the principles of the game are used in a variety of fields and by scientific communities worldwide. In the game, the player is given numbers to make educated guesses as to where the mines will be in order to both avoid the dangers and uncover all the other tiles. This principle is no different from real life, where trained industry workers and scientists use electromagnetic waves to get clues about what might be under the surface. This could mean finding pipelines running through the foundations of a building, excavating an archaeological site, or even trying to identify and disarm a minefield.

The Minesweeper game places nice neat little numbers everywhere that are both clear and easy to read but this isn’t the case with Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), the technique used by scientists and other professionals to find out what’s underground. Depending on what you’re looking for, and what materials you’re penetrating, the images can be anything from a strange-looking pattern of waves, similar to a heart rate monitor at the hospital, to a rough 3D rendering straight from a cartoon. This picture shows the variation in what you may see as you look into the internal structure of a cement supporting wall. As you can see, there are multiple ways to view it, which helps us make our most accurate guess. This can be very useful in construction or city planning, allowing people to know what is currently there to use and what should be avoided.

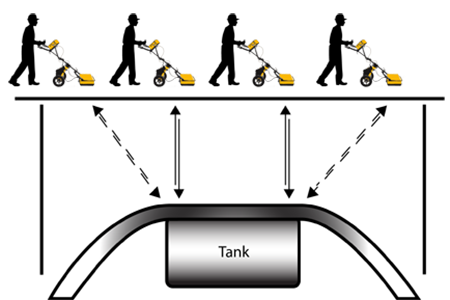

The diagram below shows a GPR device as it is pushed along a surface. The waves spread downward in a fan-like shape and you can see an object before you are directly above it and after you have walked over it. Careful attention is needed to be sure not to miss any small artifacts you may be searching for. The more constant and consistent the material is, the more complete and efficient the data will be for the user to read. Just as Superman cannot see through lead, the “radar mower” will struggle to see through certain types of materials – such as moist and clay-filled soils that have higher soil electricity conductivity.

“Mowing” the lawn to get a look at what lies under the surface. (Credit: Victor Archambault/US Radar)

Another way professionals use this technology is in oceanic plane crashes where large bodies of water are needed to be scanned for wreckage to help locate survivors. This involves a large, highly equipped plane to fly over the water – just like the ground scanning counterparts – and scan the ocean surface and below for clues as to the whereabouts of suspicious dots or shadows. It is more complex than most ground GPR designs because all elements of the radar need to be locked in place and it requires precise measurements for position correction.

Using electromagnetic waves in our daily lives continues to be more and more productive. From catching a car that’s speeding to seeing a prenatal baby in the womb, we can see its implications to help us and better humanity. Minesweeper is a popular way to procrastinate, I hope next time you kick back and relax with a game, you look at it with more of a scientific eye!

By Victor Archambault, US Radar