In today’s blog we’re having a chat with our very own Dr Lucia Perez-Diaz. As Lucia put it at the start of this year’s General Assembly, us scientists get to wear many “hats”, and she lives up to that statement. Besides a brilliant geoscientist, she is an incredible artist – also featured as last year’s artist in residence – and a budding press assistant!

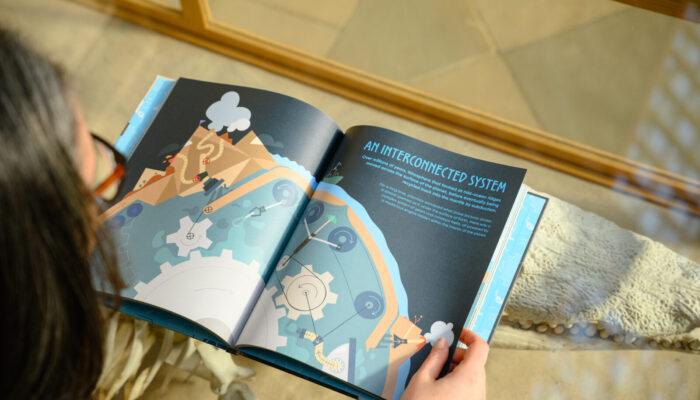

But more importantly, she is the author of “How the Earth Works”, a fascinating book that takes young readers on a journey beneath the Earth’s surface. The book that was also presented in an immersive pop-up event to the children that joined their parents at the EGU General Assembly, dives into everything from plate tectonics to the effects of climate change, making complex science topics fun and easy to understand by our VERY early career researchers.

Filled with her colorful illustrations and scientific expertise, this book is a perfect blend of education and adventure. Hence, we’re excited to hear more about how this project came to life!

How did the idea of writing this book come about? What inspired you?

From children. I was doing some events with schools where I would go to a classroom and talk to kids about what I do as a scientist. So, amongst other things, I would talk to them about plate tectonics, about the fact that Earth is like a puzzle and all it’s pieces (tectonic plates) are moving all the time with us on board. They are the reason we have oceans, and mountains, and a stable climate. Seeing their faces light up, and realizing how fascinated they were with all of this new information made me want to write a book.

Also, there were no books for children on plate tectonics that I could find. Most earth science books are about volcanoes or dinosaurs – which children love, but neither would exist were it not for plate tectonics! And whilst there are books about Earth out there, I wanted “How the Earth works” to go beyond just telling the reader about plate tectonics, and also let them into the scientific process itself, how science is done, and the many unknowns still waiting for answers.

I first met you as an artist in residence on EGU General Assembly in 2024. I’ve seen your art and really loved it. I’m curious—how did you first start combining art and science, and what drew you to bring those two worlds together?

It started in a similar way. I don’t have formal art training—I just enjoy being creative, I guess. When I was doing my PhD, I began creating things mostly to promote my own work. For example, if I had just published a new paper, I’d design a nice figure for social media to try and draw attention to it, hoping more people would read it.

Later, when I started working with schools, I needed to create some illustrations for the children—something visual and engaging for them to look at. When I was giving presentations, I preferred using my own slides instead of grabbing generic images from search engines which, most of the time, I found to be either uninspiring or wrong (or both)At first my designs were rough, maybe even a bit ugly, but I kept improving them by doing more and more over the years. It grew organically.

Do you feel that combining art with science has helped you navigate some of the pressures or challenges of your work—like stress or mental health? Has it had a personal impact on you?

Yes, I think I really enjoy having a part of my day where I can exercise creativity in some form. For most of my life, that creative outlet has been music—I have been playing the piano since I was four years old. Currently, I can play every day because I have access to a piano at home but for a long time after I moved to the UK, that wasn’t the case.

So for a few years, I couldn’t play as I used to and decided to start drawing more. I often wonder—if I had always had a piano, would I even have made a book? Maybe not, because I probably would’ve spent my free time playing instead. But because I couldn’t do that, I used my free time to draw and get into art.

It really helps me to know that I have side projects where I can just sit and sketch or come up with illustrations that might turn into something. Or maybe they won’t. Maybe they’ll just stay as personal pieces no one ever sees. But I try not to put any pressure on that part of my work. I just let it unfold naturally—follow whatever inspires me and see where it leads.

I’d really love to hear more about your science background as well. I know you’re involved in tectonics—obviously, because of the book—but could you tell us a bit about how it all started for you?

I studied geology in Spain, and after that, I moved to the UK to do a master’s degree. At the time, I was really interested in structural geology and tectonics, so that became the focus of my master’s.

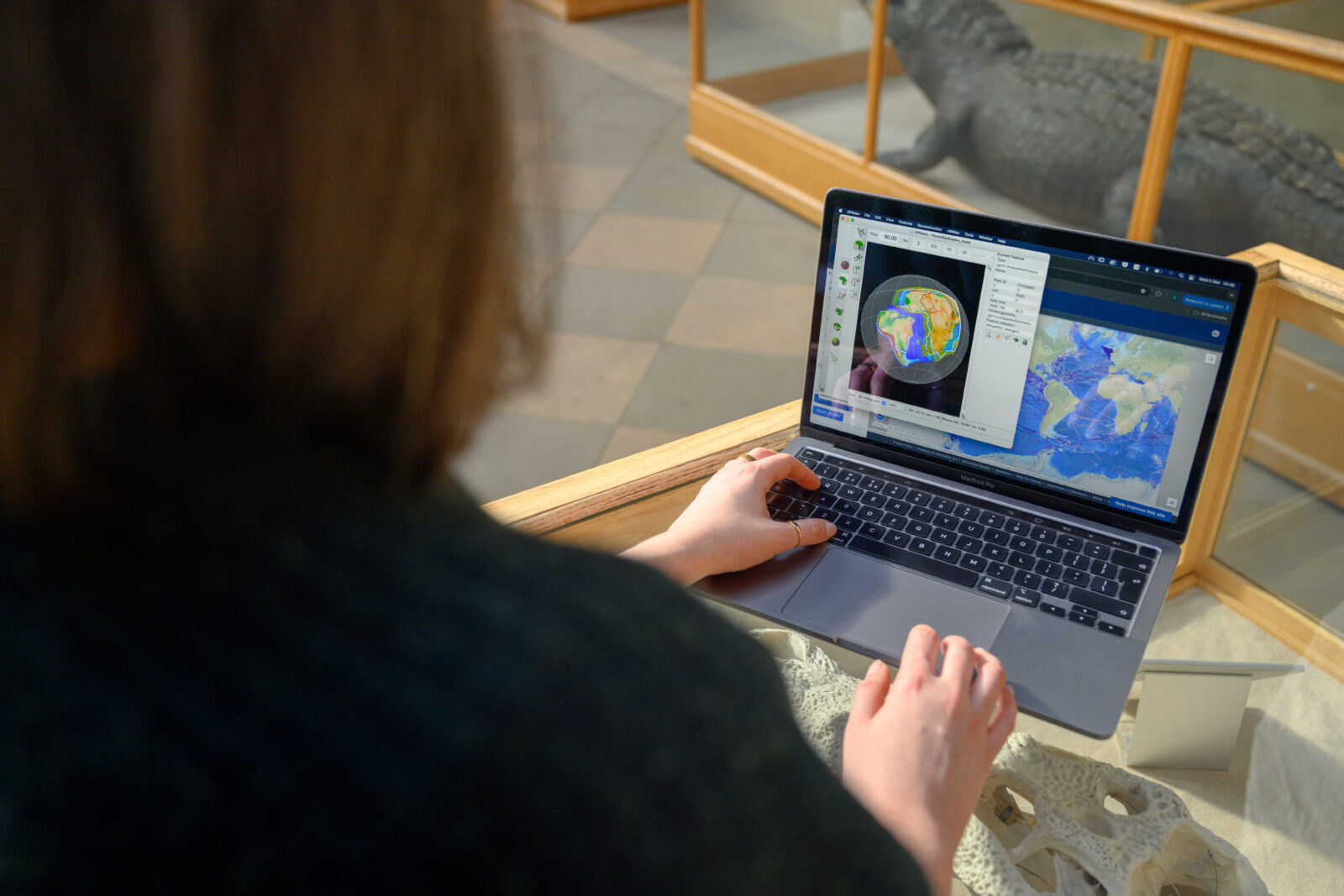

During that time, I met some researchers in the department and became interested in plate tectonic modelling. That led me to pursue a PhD in the subject. I worked on modelling the opening of the South Atlantic and how the ocean’s bathymetry evolved over time. Those models were later used by others for paleoclimate predictions—since my models show the growth of the ocean. Therefore, you can predict how the water would have been moving and how that impacted the climate.

After my PhD, I briefly returned to structural geology and did a postdoc in analogue modelling. Then I went back to geodynamics and did another postdoc, this time in Oxford, which is where I am based now. My main research question there was whether mantle plumes influence the motion of tectonic plates (spoiler alert: no, they don’t, or at least we can’t yet prove that they do)

Right before the pandemic, I saw an industry job advert seeking a researcher in geodynamics—which is quite rare. I had always worked in academia, but I thought it might be a good time to try something different. I applied, got the job, and I’ve now been working there for four years.

I still focus on geodynamics and plate modelling, and my role sits somewhere between geology and programming. I couldn’t code before my PhD, but I’ve learned a lot since then—both in academia and in industry. Now, I use computers to solve geological problems, which is something I really enjoy.

What would you say to yourself if you could go back in time, when you first started trying to incorporate art into your science? And what would you say to a young person today who is just starting out on that journey?

I’d probably say, “Worry less.” Stop stressing about whether what you’ve created is good enough or not. Who even knows that “good” is?! The truth is, in two, three, or five years, you’ll have evolved a lot as an artist in ways you can’t predict. You’ll grow and pursue what you enjoy. When you look back at your earlier work, you’ll think, “Oh, I could do this so much better.” So, there’s no point in spending too much time worrying that something isn’t good enough. It is what it is at that moment, and you’re on a journey to discovering who you are as an artist. The only way to do that is by creating—just make lots of things!

If you don’t want to share them, then don’t, it’s entirely up to you, wait until you are ready. But, when you do, you will find that people are generally incredibly supportive and love to see science-based art. The key is to not worry whether your artwork is perfect. It doesn’t have to be. Embrace beta-mode!

At EGU25, Lucia ran an impromptu pop-up event where she talked to children about the things we know (and those we don’t) about how the Earth works, and challenged them and their parents to a round of QUARTETnary (an educational card game about geological time that she illustrated, that was also featured in the EGU Geoscience Games Night).