Welcome to GeoTalk, Elizabeth! Could you introduce yourself and your background?

I’m a genderfluid glaciologist living between previously glaciated, currently glaciated, and flood-prone landscapes. I am a postdoctoral researcher at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. I did my bachelor’s in physics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and my Ph.D. in glacial geophysics at Columbia University in New York.

I am also a writer and an artist. I started university as a communications major. I worked, variously, at the dining hall and at a board game company, and as a camp counselor. Like many, I spent my early career exploring paths, from environmental journalism and early Ph.D. work to various interests in between. What emerged from that exploration was the emergence of my current specialization: glaciology.

I have always had myriad interests, and I have never wanted to disentangle writing or reading or art from my scientific work (or vice versa)—the most generative place for me is doing them all together.

Alongside glaciology, your research interrogates glacial hauntologies through the union of science and art. What is hauntology?

Hauntology is a word adopted from the social sciences. It was popularized by Jacques Derrida in the 1990s[1]. It is a compound word – haunt + ontology.

Long-melted glaciers haunt us, as terraformers that shaped the land.

Ontology is a branch of philosophy focused on the nature of being and how entities relate to one another. Hauntology describes how (meaning in) the present is affected by the culture, concepts, and context of the past, as well as the weight of failed futures. These past and future “ghosts” reach through time, changing meaning and relationships in the present.

Haunting can have a spooky connotation, but it is something “that which acts [from the past or future] without (physically) existing”[2].

How does hauntology relate to glaciers, and to ongoing glacial decline?

The way people and societies have related to glaciers[3] has changed over time. Echoes of those cultural relationships persist, affecting personal, scientific, and political decisions. Longing for lost futures—the ones where maybe we acted on the climate crisis much sooner — also affect how we relate, act, and make decisions.

It’s not all metaphorical: glaciers haunt from far away in time and space. Most people won’t go to Antarctica or Greenland; their interaction with ice is through sea level. Glaciers bring the past into the present by responding to climate over multiple timescales: long-melted glaciers haunt us, as terraformers that shaped the land.

Can you tell us more about the Glacial Hauntologies project?

In 2022, I co-founded Glacial Hauntologies with environmental artists Hannah Perrine Mode, Tyler Rai, and glaciologist Andrew Hoffman. We’re combining art and science to see what emerges.

When we started Glacial Hauntologies, Tyler and Hannah were both living in New England, on the former bed of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered northern North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Growing up, they were surrounded by erratics and moraines and drumlins, all kinds of postglacial artefacts. At the same time, Andrew Hoffman and I were going south to Antarctica.

The influences of art on science are often subtle, but they’re definitely pervasive.

As part of the (aptly named) G.H.O.S.T. project from the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, we were going to try to see through Thwaites Glacier to its bed. From New England, Tyler and Hannah looked up from the bed through the ghost of Laurentide past. On Thwaites, we tried to turn the glacier into a ghost, looking through it to try to get some information on how fast it might collapse in the future.

So the name Glacial Hauntologies felt like a good summation of the entanglement of temporalities and disciplines we were trying to engage with.

How has art informed your scientific work?

Art, reading the environmental humanities and science and technology studies, and just straight sci-fi, have all been critical to my research and teaching. This is because “it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what concepts we think to think other concepts with”.[4]

For instance, let’s take some of my work on Thwaites to measure the ice fabric with a ground-based radar as an example. Ice fabric describes the orientation of the ice crystals, and it is a result of past stresses the ice experienced. Ice remembers the stresses it has experienced, and that physical memory changes its resilience to future stresses.

I kept a visual journal for the fieldwork. I coloured these pages with oil pastels throughout the season. Oil pastels don’t really dry, so neighboring pages imprint on each other. The past pages were imprinted on the future pages, and vice versa. I published an article about this artistic practice as an autoethnography.

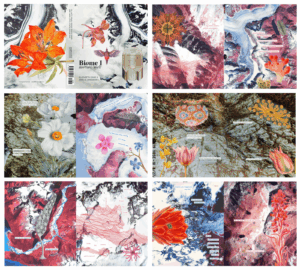

Zine: Biome I | nurture/melt, by Elizabeth Case and Amelia Greenhall, Anemone Press (2022). Satellite images (USGS Earth Explorer) of glaciers are overlaid with poems historic images form the natural sciences.

During the fieldwork, the past imprinted on my scientific work (e.g., a shoulder injury changed how I placed the radar antennas). The future also impacted our work: we were collecting data that would help us model how fast Thwaites might collapse. Every simulation run is like a ghost of a(n) (im)possible future; they change how we think about the future, and in turn then what futures we strive to realize.

I could see on the page this accidentally imprinting of the pastel drawings on the past and future bodies, and I could see how the past and future imprinted on my work in Antarctica, and all of these together helped my understanding and intuition for the geophysics I was doing, on ice fabric on Thwaites.

The influences of art on science are often subtle, but they’re definitely pervasive.

I’m always on the lookout for explicit examples of art’s impact on science, mostly because I think documenting them will help increase people’s openness to different ways of thinking, and that’s what we need in this time of crisis.

How do people respond to your science-art projects?

Mostly really positively, sometimes with eagerness, sometimes with a kind of weighted silence, sometimes with confusion or skepticism. Often it is with relief and interest. I hope that Glacial Hauntologies open up the way people relate to glaciers and the climate crisis, and play a role in (re)legitimizing the role that art, the humanities, the social sciences, emotion, and embodiment have in geophysical spaces.

Sometimes the response is immediate, and that is super gratifying. I’ve made a few zines with Amelia Greenhall, and it is amazing to see the reaction: we have sold out of all the first editions. The booklets give visual and linguistic shapes to the emotional weight of the climate crisis.

References

[1] Derrida, J. (1994). “Spectres of Marx”. Routeledge. Hauntology is introduced on p. 10.

[2] Fisher, M. (2013). “Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures”. Zero Books

[3] Haraway, D (2019) “Receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying with the Trouble Together”. in The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Ignota Press.