Recently, we had a big name in fire ecology visiting our institute. He had come, among other things, to look for records of a certain fire-adapted shrub in my university’s herbarium. While myself and a colleague helped him go through the stacks of pressed and archived specimens, I asked him why there were so little contributions to the herbarium in recent years. His response was: “People stopped doing it.”, he replied. “They moved on to do silly things, such as computer models.” The last remark was, of course, directed at me, because I am – I have to admit – an ecological modeller.

He had addressed the right person. I had a botany excursion in my first year of undergrad. Too much reminded of family holidays – which usually involved hiking up and down mountains to look at plants with the multiple generations of professional gardeners, florists and landscape architects I am related too – I decided I hated it and moved on, first to molecular biology, then to engineering and mathematics and finally finding my niche in climate and ecological modelling. I have not done another field trip in my life and I am not too sad about it.

I love modeling as a research tool. Yet I am also very familiar with the existential dread that is part of every modeler’s Ph.D. experience: The feeling that everything you do is indeed “silly”, you work with fake data in the end, and also, why is it even taking you so long to produce results – after all you’re just making things up. Other people who go to the field, produce real data, and do actual physical labour. Your job should be easy, right?

I have asked myself these questions many times, and many colleagues have asked them back to me. Yet in the end, we all managed to get our PhDs successfully and happily. So, synthesizing many heartfelt pick-me-up conversations over the last years, here are 5 insights on the existential modelling crisis – and how to overcome it.

What even is modelling?

To be (re-)convinced that modelling is a worthwhile scientific endeavor, the first step is to gain a satisfying answer as to what modelling really is. There are multiple answers to this question, and the most convincing one for me goes something like this:

“Modelling is a way to formalise complex scientific hypotheses. This allows us to express what we think we know about our system efficiently, as well as explore a large number of interactions and play (non-linear) dynamics forward, beyond what our brains can grasp and think through by themselves.”

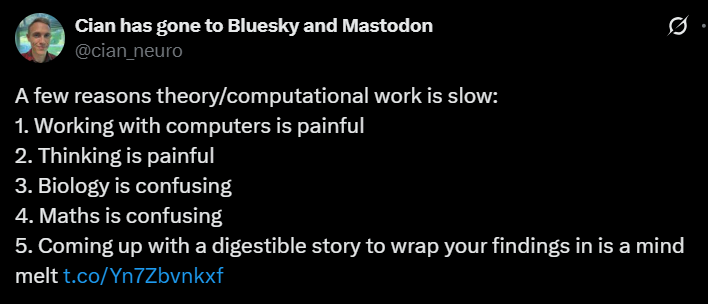

To paraphrase a popular saying: Modelling is thinking. That’s why it’s so hard! Or as neuroscientist Cian O’Leary put it in a tweet that once saved my sanity when I started out in this field:

https://x.com/cian_neuro/status/1559186365086146561

Embrace validation, even when it’s scary

Model evaluation is the bane of any PhD student working in Earth system modelling. And there is also a weird paradox that the more attention to detail a model gives, the more it gets scrutinized. Blessed are the theoretical ecologists, who go to conferences with their 3-PDE-models representing ‘species in an environment’ to talk about the cool math it’s producing – few people will ask how exactly they plan to validate their work.

As much as that sometimes feels unfair and validation gives me anxiety, I’ve come around to embrace it as an important part of the process. Validation is what gives me confidence in my work. Validation is what allows me to scrutinize my own work and feel proud of my results when I actually get around to trusting them. Validation is when I most strongly feel I am discovering something new. Also, validation can be a great way to form collaborations and interact with other researchers in your field. Which brings me to the next point, that is: Field scientists are your allies!

Field scientists are your allies

Modellers sometimes feel threatened by field scientists and their scrutiny. The thing is, many field scientists also feel threatened by modellers. Or at least feel it’s unfair when modellers come in with their big questions and bold claims, publishing flashy papers on the back of their hard work. Which does happen. So my advice is, cultivate relationships with field ecologists. Ask them to take you to the field. Read their papers. Go to their conference sessions. This is not only respectful and will help you find validation data (see point 2), it will make you understand your system better, and that will make you a better modeller. Ultimately, you’re all trying to solve the same problem, and you both contribute an important perspective to it. Part of what you’re bringing comes in the next point.

The modeller’s mindset

I recently chatted with a friend – a fellow Earth system modeller- about how, when we have life decisions to make (like career plans or dating), our brains immediately go into scenario analysis mode, playing out different future outcomes, accessing their key drivers, associated likelihoods, and downstream effects. I am sure non-modellers do that too, but what I am trying to say is that scenario analysis, thinking about the future systematically, is a skill that modellers train and tend to be good at. There are other such skills, for example, thinking probabilistically or thinking about uncertainties. So all the hours you spend ruminating about abstract stuff such as stylized climate scenarios, plant functional types or the correct probability distribution to model seed dispersal are not in vain, it’s training.

Standing on the shoulders of giants