Swamps are spooky. This is the prevailing notion from the depiction of wetlands – the saturated lands of swamps, bogs, and fens – in the media. From the folktales of Will-o’-the-Wisps guiding travellers astray to the many, many swamp monsters of Scooby Doo, the sign is clear: a scrawled “stay away from here” thrust deep in the mud, writ by centuries of storytellers. As a reputation it’s not great. It might seem obvious why wetlands have such a legacy: they’re treacherous lands, clogged with hazards like sinking mud and animal attack, which frustrate both travellers and land developers alike.

Even the language of the wetlands is used to evoke a negative response. Feelings of being “mired” or “bogged down”, of being “swamped with work”, or removing corruption by “draining the swamp.”

When was the last time you told someone you were feeling bogged in joy, wading in the morass of happiness, or indulging in the marshy mud bath of love? (Maybe you should start.) Somewhat inevitably, these emotive associations slip into naming conventions: in the 1700s, Europeans colonising the Americas referred to swamps as “dismals”. Modern media continues this tradition, with fictional wetlands frequently assigned emotive titles such as “Misery Mire” (The Legend of Zelda: A Link To The Past, 1991), or “the Swamp of No Hope” (Everquest, 1999). So common is this negative connection, TV Tropes has an entire webpage documenting it: “Swamps Are Evil“. Occasionally this depressive association becomes literal, marrying the emotive association with the hazardous reputation, trapping the protagonist’s in a nightmarish merger of landscape and psychology (“The Doldrums”, The Phantom Tollbooth, 1961; “The Swamp of Sadness”, The Never-ending Story, 1979).

Wetland scientists, however, offer a more positive perspective: wetlands are far from being domains of death, being some of the most productive ecosystems on Earth and home to some 40% of the planet’s wildlife. They absorb carbon dioxide and filter pollution; if rainforests are the planet’s lungs then wetlands are its kidneys. Science seemingly tells a story of life. Why does one story prevail over the other?

Swamp Spirits

Wetlands are the abode of the spirt. Across Europe, environmental phenomena inspired folk-tales of disembodied lights leading travellers astray. Given a multitude of names – from Will-o’-the-Wisps and Jack-o’-Lantern to Hinkypunks – the ghostly glow is likely inspired by flammable methane expulsed from the mud. These spirits have endured in the imagination of the storyteller, and are often evoked as alluring traps to protagonists, such as the entrancing corpse candles of the Lord of the Ring’s Dead Marshes ( The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, 1954) and the harmful Glares of Darkwood (2017) that illuminate difficult-to-get-to treasures.

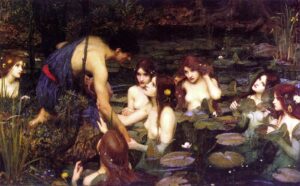

The theme of alluring spirits is common in wetland folklore, one of the the most famous being the ancient Greek tale of the Naiads who lured and then abducted the unfortunate Argonaut Hylas. Modern depictions of wetlands spirits have become increasingly complex and often sympathetic: Will-o’-the-Wisps may be helpful guides (Brave, 2012; Ori and the Will of the Wisps, 2020), whilst Kelpies – shapeshifting water-horses of Irish and Scottish folklore – depart from their traditional predatory depiction to instead aid protagonists (The Water Horse, 1990; God of War 3 Ragnarök, 2022).

The wetlands themselves can have a strong association with death: beneath the surface of peat bogs, the oxygen-free underworld can preserve bodies to a level where skin and hair are preserved. Archaeological evidence points to these bog bodies as casualties of execution or sacrifice. But it is reductive to perceive these aspects as solely a source of horror: to the communities that lived with and near bogs, these wetlands were sacred. Bogs were places to bury votive offerings at the boundary between life and death, but also places to hide and preserve food. They were not simply places of death, but functional elements that sustained local populations.

Hydrological Hazards

Beyond their spiritual association, wetlands are also hazardous. Unstable, deceptive ground can give way to deep water, and traveler’s may lose themselves in mist-wreathed swampland. Folklore often personifies this hazard as shape-shifting characters, frequently composed of amalgams of human with wetland vegetation or aquatic animal. In Slavic folklore, the bog spirit Bolotnik is said to take the form of a stone, only to toss unwary travelers into the water once stepped on. Wetland characters with similar behaviors are found throughout the folk-tales of Europe, such as Jenny Greenteeth or Nelly Longarms (England). Frequently, they take the form of a cautionary tale, depicted as preying on children in a warning to inexperienced youth, such as Näkki (Finland), Dziwozona (Slavic mythology), and Zhalezny chalavek (Berlaus). Such characters represent the wetland as an hazardous environment, a place difficult to traverse and with the danger of drowning.

Another frequently depicted hazard is the animal attack: here the exceptional biodiversity of the wetlands meets the cautionary tale. Threats may be a mundane crocodile (Romancing the Stone, 1987; “Bubblegloop Swamp”, Banjo-Kazooie, 1997) but often the animal suffers from wetland gigantism (“Attack of the Alligators!” – Thunderbirds, 1966; Anaconda, 1997) or is an amalgam of characteristic species, such as the many-snake-headed Lernaean Hydra slain by Heracles. Modern folklore merges both character and creature, depicting wetlands as the domain of elusive cryptids like the USA’s Skunk-ape (Florida Everglades) or Lizard Man (South Carolina), and a frequent antagonist in media (Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954).

The environment itself might become typified by the threat of animal attack, where waters are termed “infested” with piranhas and crocodiles, in contrast to it being their natural habitat.

Since the advent of the modern environmental movement in the US during the 1950s, modern storytellers have begun to frame these inhabitants in a more sympathetic light: aquatic characters are not mere threats but deserving targets of empathy (Lady in the Water, 2006; The Shape of Water, 2017).

Lastly, wetlands are often rendered as toxic hazard, a source of disease and poisonous waters. Before germ theory was adopted by mainstream science, miasma theory prevailed. Sometimes called “night air”, it was thought diseases were caused by foul odour produced by rot. Wetlands, like swamps and marshes, were considered loci for miasma, where the unfortunate became infected in its presence. This belief is transparent in the etymology of “malaria”, whose roots are found in the medieval Italian “mala aria”, meaning “bad air”. Although the later germ theory accounted diseases like malaria to germs and parasites born by biting insects, miasma theory contributed to the idea of swamps as a toxic environment. This trope prevails today, and with some incredible frequency in video games such as the infamous toxic swamps of the “Souls-borne” series, amongst many others (“Torvus Bog”, Metroid Prime 2: Echoes, 2004; “Southern Swamp”, the Legend of Zelda: Majoras Mask, 2000) to the extent of representing entire realms of decay (“the Garden of Nurgle”, Warhammer). Whilst precaution against disease is reasonable protection, especially in tropical wetlands, the prevailing trope of toxic waters holds little to the realty of natural wetlands. Swamps in fact act as natural water purifiers, with pollutants either buried in the soils or absorbed by the plants.

The Resisting Wilds

Beyond spiritual and environmental hazards, there is one more trope that typifies wetlands: an obstacle to progress. The expansion of European civilization on the continent has been typified as “one of protracted struggle against the abject, waterlogged expanses marking its own inner and outer frontiers” (McLean, S., 2003, “Céide fields: Natural histories of a buried landscape”. Landscape, Memory and History: Anthropological Perspectives, pp.47-70).

Wetlands were considered wastelands without value, and thus lands to repurpose.

For example, from the 1200s, England’s peatlands were appropriated by barons, and the previously common land was transformed and exploited. This was shaped by the perspective that the peatlands were a wasteland: unproductive and without value unless capitalized on. As Europe exerted its imperial ambition, this perspective transferred to the colonies. Swamps and marshes were an obstacle to travelling colonists, and frustrated attempts to transform colonised land into agricultural and urban territory. The resulting exploitation, destruction, and repurpose of wetlands has contributed to 20% of the worlds wetlands being lost since the 1700s, with more than half being lost in the US, Europe, and China.

As wetlands continued to frustrate development, they became spaces of refuge and resilience to the destructive and exploitative ambition. In the United States, for example, swamps became a home to criminals and escaped slaves. This perception has remained in modern media, negatively depicting wetlands as a den for criminals, murderers (Hatchet, 2007; Swamp Murders, 2013; Zone Blanche, 2017) and cults (The Call of Cthuhlu – H.P. Lovecraft, 1926 ). Rarely are swamps depicted positively as refuge, although this appears to be more common in children’s media (Shrek, 2001; The Princess and the Frog, 2009; Maleficent, 2014).

Me And My Swamp

Wetlands are also a home. In contrast to the perspective of wetlands as frontier wasteland, communities have inhabited bogs, fens, and swamps for millennia.

As wetlands were destroyed, so were people displaced from their traditional lands.

For example, the Ahwaris, inhabitants of Iraqi marshlands, inhabited these wetlands for at least a millennia before many were displaced as the marshes were drained in the 1990s.

In storytelling, the inhabitants of wetlands often presented as uncivilized or primordial. Embodying mystical archetypes, they a frequently hermits in touch with the supernatural who help the protagonist (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, 1980; The Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, 2006), manifestations of nature (Swamp Thing, DC Comics), malevolent witches (Castle of Wizardry, 1984; Baldur’s Gate 3, 2023) or the varied, frequently inaccurate and historically negative, representations of Hoodoo practitioners (Skeleton Key, 2005; The Princess and The Frog, 2009). Eve’s Bayou (1997) subverts this mystification, with the protagonist’s fearful assumptions of Hoodoo spirituality contrasted against the practitioner’s reality.

Depictions of communities are less common, with historical media frequently presenting them as antagonistic and racist archetypes of wetland tribes. Communities are also depicted in a supernatural manner, and often positioned in opposition to environmental destruction: FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1989) depicts the resistance against would-be despoilers form the perspective of a fae community, for example. Annihilation (2014) subverts the dynamic of resistance and repurpose, where the transformative force is turned on humanity through the mutating, spreading alien everglades which threatens to swallow and reshape civilisation. The Beast of the Southern Wild (2012) stands out, in a rare instance of a story told from the perspective of a community living in a Louisana bayou.

The Fluid Space

Wetlands occupy a complex position in our social consciousness. More than just spooky, they are a transitional realm, their identity as fluid as their marshy soils. They are a place of danger and a sanctuary. At once a primordial land which frustrates development, and a millennia-old home to humanity. They are the realm of the spirit and a hotspot for biodiversity. Occasionally, this fluidity is captured in storytelling: in Princess Mononoke (1997), where the mossy pools at the forest’s heart make the home of the Great Forest Spirit, who both gives life and takes it away. In the Baldur’s Gate 3, the “Sunlit Wetlands” and the “Putrid Bog” are both the same area, the former revealed to be an illusion veiling the latter. The key difference is seemingly aesthetic, with both home to thriving – if hazardous – biodiversity. The idea that wetlands are a haven for life appears incorrigible however, as even in the apocalyptic wasteland of Mad Max: Fury Road, it is the muddy wetlands where life is at is most obvious, flocked as it is by crows. The depiction of swamps has become increasingly sympathetic – more than haunted hydrology or an unproductive wasteland, they are recognised as places with intrinsic value.

hannah

Really enjoyed this, thanks!

Chris Tanner

Great exposition of the psychological backdrop behind our treatment of natural wetlands in many parts of the

world. Here in New Zealand we have lost 90% of our natural wetland, mostly in the last 150 years since European colonisation through conversion into pastoral agriculture. If it had been China or Japan colonising, it would likely have been into rice paddy instead.