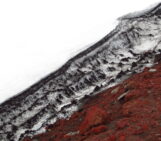

The Montejaque dam, with its 84 meters of height, is one of the first vaulted dams built in Europe. Currently, it remains only as a vestige of one of the major hydroelectric projects by the “Sevillana de Electricidad” company. Preliminary studies for its construction began in 1917. Some of these studies indicated that the project was unfeasible due to the karstic nature of the terrain, while others were simply incomplete. Finally, in 1923, construction began, boosting the economy of nearby municipalities such as Montejaque, Benaoján, and Ronda (Málaga, SW Spain). Hundreds of people were hired to carry out the project, which was completed relatively quickly in just nine months. However, once the dam started operating, water leaks appeared, preventing its proper use. The stored water seeped through cracks and sinkholes in the limestone rock, particularly through the cave known as “El Hundidero.” Between 1929 and the time of the Spanish Civil War, teams of Spanish and Swiss engineers worked to prevent these leaks and thought that the only way to achieve it was by injecting concrete into the cracks of the limestone rock. Some of these concrete “plugs” still exist today. However, due to the impossibility of retaining the water, the dam construction project was finally abandoned in 1947.

Currently, during the summer, the reservoir is completely dry, serving as a grazing area. However, during the rainy season, the water starts to accumulate, forming a huge artificial lake that interrupts rural roads and access to different estates.

Ahora, en español:

La presa de Montejaque, con sus 84 metros de altura, es una de las primeras presas abovedadas construidas en Europa. Actualmente, solo queda como un vestigio de uno de los grandes proyectos hidroeléctricos de la empresa Sevillana de Electricidad. Los estudios previos a su construcción se iniciaron en 1917. Algunos de estos estudios indicaban que el proyecto era inviable debido a la naturaleza kárstica del terreno, mientras que otros estaban simplemente incompletos. Finalmente, en 1923, se inició la construcción y esto impulsó la economía de los municipios cercanos, como Montejaque, Benaoján y Ronda (Málaga, SO de España). Cientos de personas fueron contratadas para llevar a cabo la obra, que se completó relativamente rápido en tan solo nueve meses. Sin embargo, una vez que la presa comenzó a funcionar, aparecieron filtraciones de agua que impidieron su correcto aprovechamiento. El agua embalsada se filtraba en cuestión de horas a través de grietas y sumideros de la roca caliza, especialmente por la cueva conocida como el Hundidero. Entre 1929 y la Guerra Civil, equipos de ingenieros españoles y suizos trabajaron para evitar estas fugas y pensaron que la única forma de lograrlo era inyectando hormigón en las grietas de la roca caliza. Algunos de estos “tapones” de hormigón aún se mantienen en la actualidad. Sin embargo, ante la imposibilidad de retener el agua, el proyecto de construcción de la presa fue finalmente abandonado en 1947.

En la actualidad, durante el verano, el embalse se encuentra completamente seco, funcionando como zona de pastoreo. No obstante, en la época de lluvias, el agua comienza a acumularse formando un inmenso lago artificial que interrumpe los caminos rurales y el acceso a diferentes fincas.

Photo and caption by Antonio Jordán, shared on imaggeo.egu.eu.

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.