In July 1923, 100 years ago this month, scientists and explorers made an extraordinary discovery that forever changed our view of dinosaurs. An expedition to the Gobi Desert in Mongolia unearthed fossilized dinosaur eggs, in a nest, confirming that dinosaurs laid eggs like the reptiles that scientists at the time thought dinosaurs were.

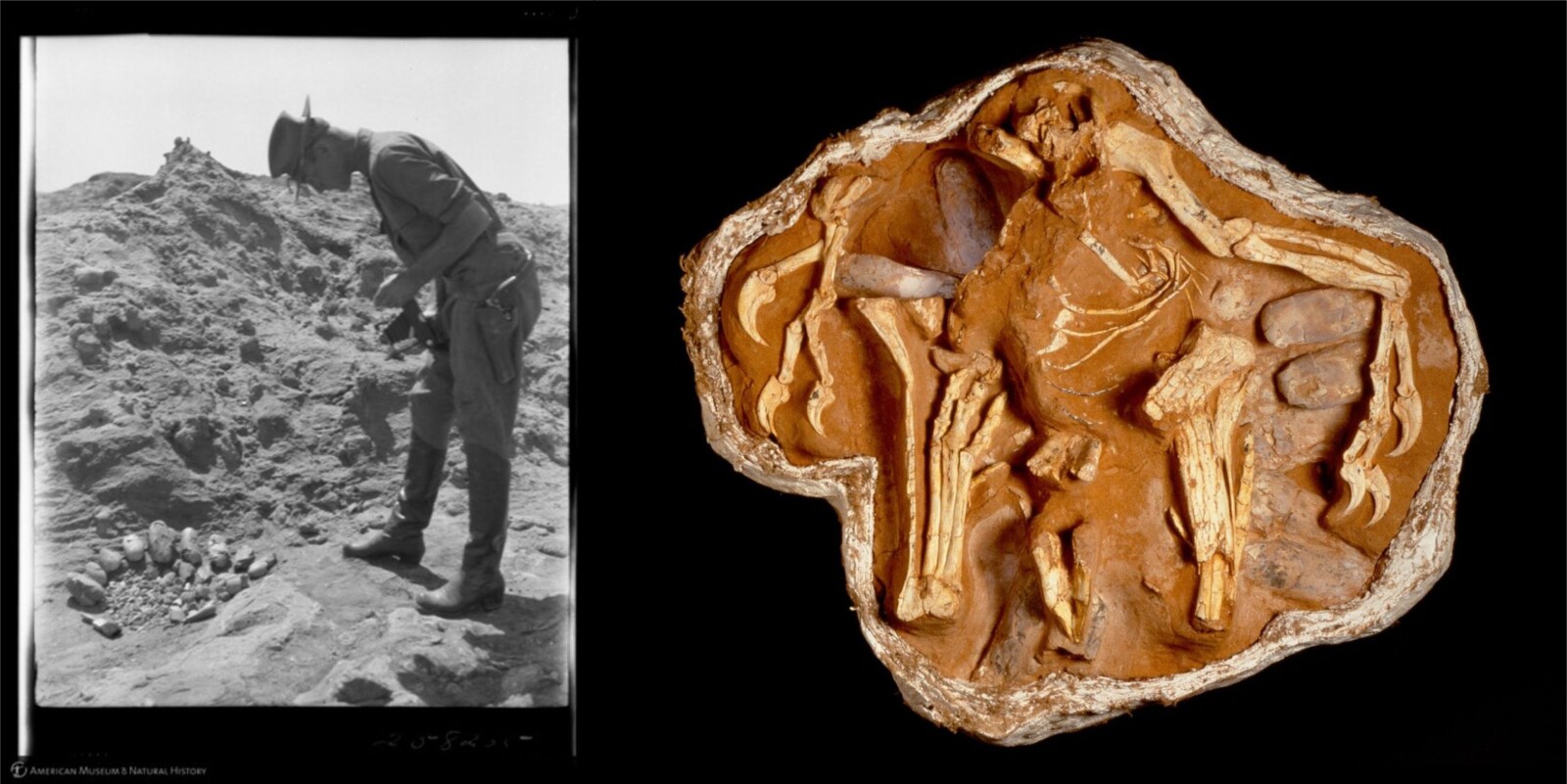

Left: Roy Chapman Andrews photographs a nest of a dozen dinosaur eggs in Mongolia in 1925. Credit: Andrews, Roy Chapman, 1884-1960 (photographer), AMNH Research Library | Digital Special Collections, accessed July 17, 2023 Right: The original discovery: Nesting Oviraptor, sitting on her eggs, though at first she was thought to be stealing them. This specimen is housed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Credit: D. Finnin / ©AMNH

The find was announced in newspapers at the time, to much fanfare. The expedition leader, Roy Chapman Andrews of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, became a celebrity.

The eggs were initially assigned to be those of a Protoceratops, a Cretaceous-aged horned ceratopsian relative of the Triceratops. That’s because the expedition team had found several Protoceratops skeletons in the same area. After further exploration of the nest, however, bones of a birdlike dinosaur that had never been seen before were also found in the nest. The team decided this dinosaur must’ve been stealing the eggs and thus named it Oviraptor, or “egg thief/egg seizer.”

It took another 70 years for scientists to realize that Oviraptor had been misnamed and miscategorised as an egg-thief. That dinosaur with eggs in a nest wasn’t stealing and eating the eggs. She was sitting on a nest, protecting her eggs from a vicious sandstorm that ultimately claimed her life.

“The eggs, nests and embryos [discovered over the last 100 years have] inspired an entirely new field of investigation, providing insights into dinosaur reproduction, physiology, metabolism and behaviour,” wrote Marco Romano of Sapienza University of Rome and Michael Novacek of AMNH this year in Nature.

The Expedition(s) and Discovery

The eggs were discovered during the second year of Andrews’ expeditions in the Gobi, which he described as the Great Central Asiatic Expeditions. In 1921, Andrews and his team set off for the Gobi with visions of discovering where early humans and other early life evolved. From 1921-1930, the team combed an area 3,200 kilometres by 1,600 kilometres of harsh desert and badlands, scorching hot in the summer, dangerously cold in the winter, replete with danger.

Andrews and his team found their first dinosaur bones in 1922, bones of Protoceratops, serendipitously. The expedition — a crew of 40, give or take, travelling by camel and early car — had gotten off track, as Novacek and colleagues wrote in Scientific American. A crewmember wandered off a little ways and found bones. This discovery marked the beginning of an extravagance of fossil finds in the Flaming Cliffs, red cliffs and spires reminiscent of the stunning red landscape of Monument Valley in Utah and Arizona. The next year, a team member named George Olsen excitedly told the team he’d found dinosaur eggs. At first, Andrews wrote in field notes, he and his colleagues didn’t believe Olsen, figuring the so-called eggs were sandstone concretions or something similar.

But when Andrews and the team examined the eggs poking out of the sandstone, they realized “there could be no mistake,” he wrote. The “brown, striated eggshell was so egg-like … we had to admit that ‘eggs are eggs’ and we could make them out to be nothing else … It was evident that dinosaurs did lay eggs,” he wrote.

What initially looked like a nest of three eggs turned out to be 25, and it was the first of many nests found.

Over the first couple years of the expeditions, the team uncovered and transported 100 fossil dinosaurs back to New York, including 25 dinosaur eggs, at least one of which they auctioned off to raise funds for further expeditions. They also unearthed dozens of eggs and nests, lizards and early mammals, including the largest meat-eater known, and much more — “a staggering body of observations, records, measurements, photographs, films and collections,” according to the AMNH archive.

Over the last half of the expedition, the political climate grew tenser until eventually the team was pulled out by AMNH in 1930. No one from the West returned for decades, not until tensions eased after the Cold War. 1990 marked the first return expedition for AMNH scientists.

The Eggs

In 1993, 70 years after the Andrews team’s discovery of dinosaur eggs, AMNH palaeontologists Mark Norell and Michael Novacek and their team uncovered the eggs’ layer. The only true way to discern the layer of an egg is to find an egg with an embryo in it. Deep in the Gobi, at a site called Ukhaa Tolgod, the scientists unearthed a nest of eggs that contained embryos. The embryos had cranial and other skeletal features that provided matched Oviraptor philoceratops. What’s more, these eggs are a perfect match for the 1923 eggs, the most common eggs found at the Flaming Cliffs, Norell and colleagues wrote in Science in 1994. They were identical in size, shape, surface ornamentation and microstructure, the team noted.

“Our evidence shows Oviraptor died while incubating eggs.” It was a stunning find — the first time non-avian dinosaurs could be proven to brood like modern birds. And it perfectly explained the find of the Oviraptor bones atop the nest in the 1923 find. That Oviraptor who died in the sandstorm had been sitting on her eggs, just like the chicken or robin in your backyard does.

Adult oviraptorid sitting on a nest of eggs with embryos inside. Photo by Shundong Bi, Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Fast forward another 28 years to 2021 and another astonishing discovery: a well-preserved skeleton of an oviraptorid showing precisely how it curled in its egg just prior to hatching. Other astounding finds include a Velociraptor clawing and killing a Protoceratops. And the find that dinosaurs repeatedly used the same nests or nesting grounds.

According to a report submitted to UNESCO in the process of nominating the Cretaceous Dinosaur Fossil Sites in the Mongolian Gobi as a World Heritage Site, more than 80 genera of dinosaurs have been found in the Gobi in more than 60 fossil sites. The Gobi is considered by many as the largest dinosaur fossil reservoir in the world.

Truth and Mythology

Other little-discussed facts are worth mentioning. First, the Andrews expeditions weren’t actually the first to find dinosaur eggs. Rather, the first dinosaur eggs were found in the mid-1800s in the south of France, but as dinosaurs as a concept were relatively new on the scene, the eggs weren’t described as dinosaur eggs at the time. Rather, in 1994, palaeontologists confirmed that those eggs that were described decades before Andrews’ team’s find, were actually the first-described dinosaur eggs. Second, though many people say the character of Indiana Jones was based on Andrews, he probably wasn’t, at least not directly. The character was based on swashbuckling explorers in early moving pictures. Some of them were likely based on Andrews, though.

Third, while the Andrews expeditions were important for science, they were not without controversy. Andrews’ team removed hundreds of specimens from Mongolia and brought them to the U.S. While that was common at the time — and throughout history, it’s been common for Western scientists to remove artefacts from other countries — it doesn’t make it right. In addition, Andrews’ tales of the riches of fossils from the region kickstarted a black market for fossils that led to countless fossils being removed from the country for decades, as Thea Boodhoo wrote for EARTH Magazine. Efforts have been made in recent years to repatriate fossils to Mongolia and to involve the people of the region in their rich heritage.

It’s not hard to see why ancient travelers along the Silk Road were perplexed by the lion-sized, taloned and beaked bones they found, guarding nests of eggs. They described the creatures as griffins. We call them Protoceratops, the first dinosaurs described by Roy Chapman Andrews and his team in the Gobi. Credit: M. Shanley / ©AMNH

Although these fossils were the first of their kind recorded in modern scientific literature, local people, traders and travellers have long found strange objects in the earth that defied understanding. A mysterious creature with the body of a lion, the beak and talons of an eagle? An ancient Greek, walking the Silk Road, would tell you that these were the remains of a mythical griffin … a modern palaeontologist would call it a Protoceratops.

Oviraptor, Velociraptor, Tarbosaurus, Psittacosaurus, enormous mammals, and many other incredible extinct animals have also been found in the region. From these otherwise inexplicable finds came some of the gods and monsters of Greek mythology, according to Adrienne Mayor, a classical folklorist who wrote The First Fossil Hunters: Palaeontology in Greek and Roman Times. As Brent Breithaupt, U.S. Bureau of Land Management Wyoming Regional Palaeontologist, told me years ago for a story for Geotimes magazine, myths are often not “tall tales, but rather the interpretation of people at the time.”

With each new advance in science over the last 100 years, modern fieldwork is now 1,000 times easier than fieldwork 100 years ago, and as scientists collaborate across language barriers and borders on new discoveries, with the help of satellites, advanced computer technologies and genetics, you have to wonder what we’ll learn next!