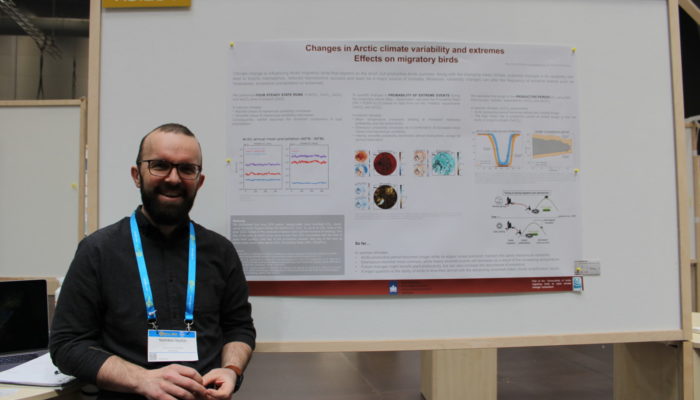

Changes in Arctic climate variability and extremes may have significant impacts for migratory birds, according to a study presented at EGU23 by Nomikos Skyllas, a PhD student from the University of Groningen.

Many species cross continents during their seasonal migration patterns, travelling from as far as Africa and South America to northern regions such as Siberia and the Canadian Arctic. If you’re not a bird enthusiast, you may not even realize that some of your familiar neighbourhood birds are only part-time residents and therefore vulnerable to these changes. According to the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, the North is estimated to host almost 300 bird species during the breeding season, including 50 per cent of all shorebirds and 80 per cent of all geese. It’s just one of many ways that the intensified effects of climate change in Arctic regions will have far-reaching consequences for the rest of the world.

Skyllas’ work focuses on changes to the length of species-appropriate conditions for these Arctic migratory birds each year. He is part of a Dutch consortium focusing on a single research question: are Arctic migratory birds over the edge?

In 2020, the project was awarded a one million euro grant by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) as part of the Netherlands Polar Programme. While there may not be an intuitive connection between the Netherlands and the Arctic, the country is home to a significant number of migratory Arctic birds during the winter months, and as the group wrote in their proposal, they “bear an international responsibility to accommodate them.”

To find out more, we spoke to Skyllas as he shared his work at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly on Tuesday.

So how will climate change impact these birds? Is it actually things like mortality, or more along the lines of changes to reproductive success?

Skyllas: Well, that’s the big question we’re asking right now. So far I have some preliminary results, and I can tell you a few things. The higher altitude means that the Arctic does warm faster than the rest of the planet. It’s called Arctic amplification, and it’s a big issue. Say you are a bird wintering in the Netherlands. You leave at the right time based on the conditions in the Netherlands.

But you realize, as you’re flying, that the Arctic is warmer than you expected. So you will, as a bird, skip some stops, skip some meals, so you arrive on time eventually, but you’re exhausted. You need to spend more time resting and eating before the breeding period can begin. Now your chicks don’t have high quality food, they eat deteriorating food. So basically it creates mismatches, where birds are not able to time their arrival as well as they did before.

What are some other examples of mismatches caused by climate change you’ve found in your research?

Skyllas: The snow-free time window becomes longer as weather warms, so on average snow is melting a month earlier and accumulating a month later. What happens inside that longer time window? What I’ve found is that precipitation increases. While the window of opportunity to breed is wider, rainfall can be a big problem for chicks because they’re not very good at regulating their body temperature. Future changes may also increase the abundance of predators.

And while more rain, higher temperatures and more time also mean you will have more grass, we’re not sure that the quality of the grass will improve. What has been found with local experiments is that the good quality peak remains narrow.

Were you doing local, on-the-ground experiments as well or mainly extrapolating from existing data on temperature, snowfall and precipitation and combining it with what we know about ideal conditions for birds in order to make predictions?

Skyllas: Our work is part of a big consortium with many bird ecologists. I based this study on work done by Thomas Lameris, who is based in the Netherlands but frequently does research on-site in Siberia. We also have data from Greenland and Svalbard. But my work is really based on climate data. I’ve noticed that ecologists often work on very high-resolution, very small datasets.

That’s what’s so interesting about your findings. Many researchers who focus on birds seem to be looking to answer very specific questions, and are able to tell you that they’re seeing feathers shortening by an average of a few millimetres every year or things like that, but it can be hard to see the full scope of what that means.

Skyllas: Exactly. I don’t claim that with climate models, you can zoom into a tiny village and explain what’s happening there. That’s not possible because of the scale and the spacial resolution, but they can be very useful in giving you big picture, general changes.

Where I’m living, in the Northwest Territories, a lot of species we typically see in more southern regions are moving north. Is the same being noticed with birds? Have some birds been able to use the warming effect to their advantage, and expand their habitat?

Skyllas: There have been studies that have shown that birds have higher probabilities of successful reproduction when they break into new territories. So when they’re able to find the conditions they found in the past in a new territory, usually further north, when they travel further to the north, they’re able to be more successful, but this strategy may require more energy. This has been observed, not by me, but I have read about it in literature.

What I can say is that in the future, high Arctic snow cover will become more similar to what happens right now in the subarctic, so that gives me one indication. I have also done another analysis, which is where Svalbard birds can find the conditions they have right now in a warmer climate. It turns out that for my two model simulations, if Svalbard birds wanted to keep having the same window of opportunity, the same productive period, they would have to go to the coast of Greenland.

But I think that’s as far as I can go without entering species distribution model territory. We do collaborate with scientists who do species distribution in our consortium, and I can help by providing them with the climate data. So I really love doing that.

This article has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.