Like a reasonably large proportion of the population, I have colour vision deficiency (also known as colour deficient vision or colourblindness). I’m not going to get into the technical aspects of what this is like as they are covered well here and here, and you can do an Ishihara test, and other tests here, to check your own vision. The other reason I’m not going to discuss the technicalities of what some might call ‘an affliction’ is basically because it is all I’ve ever known. Having the usual questions of “what colour is this?” or “what colour do you see the sky/grass/this tree/this other thing as?” has become routine.

Equally, from my first diagnosis at about age 4 or 5 (as a result of doing “odd” things like colouring the sky or sea pink), my colour vision deficiency has at times felt like a barrier. This stems from being told, as soon as you’ve been diagnosed, that you cannot do certain things, like be a doctor or a surgeon or a pilot. Not that I wanted to do any of those things or am unhappy with my chosen line of work. However, and this is just my own viewpoint, I’ve never found it to be a barrier in the geosciences, perhaps with the exception of one or two things that relate to the questions above. This is especially true for areas of the Geosciences that people generally consider to be very reliant on colour identification, such as mineralogy.

So what choice pearls of wisdom or take-home messages do I have for you? Firstly, to those of you who have colour vision deficiency, don’t panic. It is not a barrier to a successful career in the Geosciences, far from it. You see the world the way you see it; you will learn what minerals look like to you. And because the colours might be slightly different from what everyone else sees, you may actually rely less on colour and more on other (more useful and diagnostic) criteria for mineral identification.

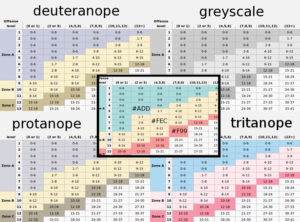

You can test the colours of a chart, (center), to ensure that no information is lost for people with a colour vision deficiency (Grolltech, Wikimedia)

There are also lessons for those of you with full colour vision. Remember that 8% of men and 1 in 200 women have a colour vision deficiency. Don’t ask people to identify the green or red mineral in a hand specimen or thin section without being more specific; use cross hairs or point it out with your handy scratcher or pencil. Check your posters and powerpoints for suitability when presenting at conferences or when teaching using tools like this. And don’t ask the usual questions; they get boring. Instead, be supportive and encouraging, and emphasise that this isn’t a barrier to success, especially not in the Geosciences.

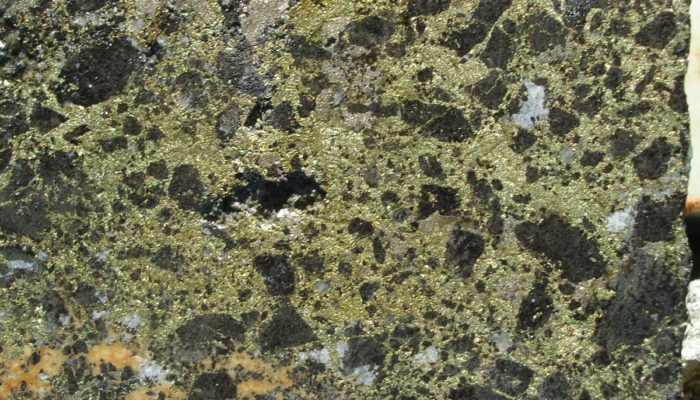

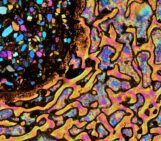

When you tell someone, be they a colleague, a student, a peer, or whoever, that you have a colour vision deficiency, there is sometimes a tendency to ask how you can do certain things in geology, especially in mineralogy. However, as (hopefully) many of my fellow graduates of the year of 2002 from the University of Edinburgh can attest, I was actually pretty darn good at mineralogy as a student, especially at thin section work. I have also demonstrated (or TA’d if you are in the US) and taught igneous and metamorphic petrology and mineralogy courses for more than 16 years now and a lot of my own research has involved mineral identification at a variety of scales. So, you might ask, how does that work? It’s simple really. I see the world the way I see it; biotite, clinopyroxene, quartz, garnet, whatever the mineral, it looks to me the way it has always looked.

Mineral identification is often learned empirically, and my learning experience is the same as yours, I just view the colours of the world slightly differently. I may struggle if you ask me “what is this green mineral”, but if you put that mineral under the cross-hairs of your microscope, I’m pretty sure I can identify it. Unless you have picked a really odd rock in a deliberate attempt to confuse me. The same might go for comparing birefringence colours to a Michel-Levy chart, but this isn’t always easy anyway, right? And as we all should know, colour is not always diagnostic; minerals need to be identified using a range of different criteria, of which colour is just one, and not a very useful one at that.

Jean-Pierre Gattuso

I am an editor of the EGU journal Biogeosciences and have suggested long ago that no paper should use the rainbow color scale and mix green and red colours in the same plot.

– http://betterfigures.org/2014/11/18/end-of-the-rainbow/

– http://geog.uoregon.edu/datagraphics/EOS/

This has been a struggle. This issue is mentioned in the instructions to authors but the rule is not strictly enforced.

Iain Allison

Simon:Thank you, interesting comments. I, too, have a mild form of the same ‘affliction’ and I, too, refer to the Grant Institute as my alma mater but graduated a few decades before you. Like you, I never had a problem with mineralogy but I did prefer the physics-related areas of geology to the chemistry-related ones and so became a structural geologist. And I’ve taught geology in all its forms at the Universities of Strathclyde and Glasgow. My children, and now my grandchildren, know my naming of colours can be different from theirs!

Simon Jowitt

Hi Iain, thanks for the post. I think that final part of your comment is the hardest thing for people to understand as colour is just part of everyday life. It’s sort of hard to explain to people how the world looks when you don’t know how it looks to other people. I’m sure there’s an allegory in there somewhere. I’m just thankful for RGB and CMYK codes (and before that labelled coloured pencils!) so I can be consistent in colour usage etc…