In this guest blog post, Nick Arndt, Professor at the Institut des Sciences de la Terre, Grenoble University, reflects on the pressures on academics to publish more and more papers, and whether the current scientific output is sustainable.

Imagine a highly productive car factory. Thousands of vehicles are built and each is tested as it leaves the factory; then it is stored in an enormous parking lot, never to be driven. Science publication is going this way. It is becoming an industry that produces without reason or limit, with no consideration whatsoever of whether the product is ever consumed.

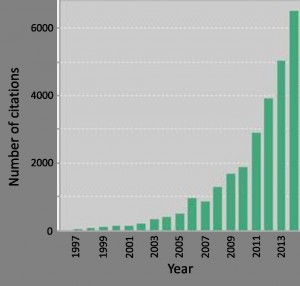

A successful scientist is now required to publish 5 or more papers per year, the pressure coming from the need to foster the H-index and boost the total number of citations. Twenty years ago, to publish a paper in Nature or Science was all very well, but nothing that special; now, according to persistent rumours, a Chinese researcher can buy a used car with his share of the reward his university receives for such a publication.

Some months ago, a geoscientist (let’s call her Tracy) saw that Earth and Planetary Science Letters (EPSL) had published over twice as many papers in 2014 (about 630) than in 1990 (about 250). She recalled that twenty years ago there was just Nature; since then the publishing house has spawned Nature Geoscience, Nature Climate Change, Nature Arabic Edition and 36 other siblings, not to mention Nature Milestones, Networks, Gateways and Databases. In 2001 Copernicus Publications launched its first highly successful open-access journal; now it publishes about 50. Each day Tracy receives an email invitation to contribute to, or edit, a newly launched publication; such as the Comprehensive Research Journal of Semi-Qualitative Geodesy, impact factor 0.313, which “provides a extraordinary podium where scientists can share their research with the global community after having traversed numerous quality checks and legitimacy criteria, none of which promises to be liberal”. An editor of one well-known biology journal now handles 4300 manuscripts per year.

The explosion in the number of new journals means there are quite enough portals for Tracy to publish her annual quota, but are these papers ever consumed? What proportion is ever read? One well-known geoscientist published 114 papers in 2014, more than two per week. Did he have time to read them?

Imagine an artisan in a Morgan car factory, carefully hand-crafting V6 Roadsters, each car taking two full weeks to finish. Some of these become collection pieces, stored and never driven. Geoscience papers are going in the same direction – the time taken to write them is far, far longer than the time dedicated to reading them.

Many of us now admit that the only time we read a paper from cover to cover is when we do a review (the equivalent of the test drive). Tracy knows from talking to others that her own papers are never read thoroughly, even those that are remarkably highly cited.

Tracy has resolved to become sustainable, which means that she will publish no more than 2 papers per year and will train no more than two PhDs during her career. By avoiding shingling and taking care with the writing, the two papers will be quite sufficient to report the results of her research (at least those that warrant publication). The fate of some of her PhD students worries her; does a thorough knowledge of Semi-Qualitative Geodesy really help Judith, who now works in a bank, or Christophe, a mountain guide? She thought that 2 PhDs would be quite sufficient, one to replace her when she retired and the other reserved for that one student who was brilliant.

The sustainable geoscientist has a very mixed opinion of the science funding industry. She applauds the measures taken to help assure that money goes to the best science, but deplores the time and effort that is consumed. She spends a third of her time writing proposals to one agency or another, knowing that the chances of success are far less than one in ten. Another large slice of time is spent reviewing the proposals of others, a exercise she suspects is futile because the final decision will be based mainly on the H-index. She looks forward to the time when her grant proposals will be judged from the content of her two publications per year, which will be read thoroughly by all members of the evaluation committee.

By Nick Arndt, Professor at the Institut des Sciences de la Terre, Grenoble University & EGU Outreach Committee Chair

Editor’s note: This is a guest blog post that expresses the opinion of its author, whose views may differ from those of the European Geosciences Union. We hope the post can serve to generate discussion and a civilised debate amongst our readers.

Pingback: Are you experiencing science overload? – Watershed Notes

Pingback: GeoLog | This calls for a celebration: GeoLog’s 1000 post!

PH Blard

Elsevier published an Ethical Guide to prevent salami publication…

PH Blard

Elsevier published an Ethical Guide to prevent salamy publication… But that was back 2015, maybe already expired? (joke)

https://www.google.fr/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwivuLTJ1q_MAhWDvhQKHVKGASgQFggkMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.publishingcampus.elsevier.com%2Fwebsites%2Felsevier_publishingcampus%2Ffiles%2FGuides%2FQuick_guide_SS02_ENG_2015.pdf&usg=AFQjCNGxtAQgPcpOUvKygVDeNs6H_oehtA

Bernard Marty

Hi Nick,

I generally agree with what you say, with a few reserves.

You cite the case of a journal’s number of paper published each year that increased by a factor of 2.5 in 26 years, however this should be compared with the growth of the geoscientists community during this period of time, especially because emerging communities such as in Asia are now at an excellent level and contribute to top rated journals.

The second point is about the number of PhDs that we shopuld train in a lifetime. I disagree that we should limit this number to 2 in order to (i) insure our replacement, and (ii) pick up a brillaint student (does it mean that we need a not brilliant to replace us ? joking). Training a PhD student is not an egocentric operation, but it’s a formation that will be useful for all the society, even for banks. If we had more people formed at the rigor, truth, curiosity and intellectual merit and probity that requires a PhD, we should certainly have much better politicians, economists, managers etc.

By the way, nice gig, Friday night !

Cheers

Bernard

PH Blard (CRPG Nancy)

Hi Nick

I am very gratefly that you wrote this blog note about this crazy inflation of papers. I definitely agree. Quantitaty does not mean quality. And worse than this: the present situation has reached a point where quantity affects quality. Plenty of papers that would have been much better and consistent are now cut to be published in the form of 2 or 3 different small papers, just because of this h-index and citation race.

I have an idea about a possible solution, but that is very provocactive. I however think it is worth discussing: this idea is to introduce a quota of publication per researcher and per year.

This already exist in conferences: only one publication per first-authors is allowed (+ 1 invitation). This is justified by the limited time of conferences (5 or 6 days). But same is true for scientific articles: we only have a limited amount of days in our life, and ony 24 hours a day… and we still need to sleep and eat, or do some other stuffs every day, no? If every scientist co-authored 20 papers a year, who would be able to make careful reviews and who would read this huge amount of material?

Moreover this quota system already exists “downstream”, since we often have to pick 5 (or less) selected publications when we submit a project or apply for a position.

With an annual quota of publication, every scientist would have more time to do better work and have more time to do careful reviews and read thoroughly much more other papers. Then quality could have a chance to become more important than quantity.

But that’s difficult to imagine how such a quota system could be implemented. I guess this should be decided by the main worldwide Academies of Sciences, and that different quotas should be established for different disciplines. 2 publications as first authors and 5 publications as co-authors would already leave a lot of space, no? These numbers are just suggestions, I have no definitve advice on this number.

I swear that my motivation is not cut the wings of people publishing more than me, but just an idea to propose a better way to promote good science. Anyway, even with a quota system, I think that the brightest and more productive scientists would still produce outstanding and high impact papers, and that they would still be more quoted than others.

Cheers

PH

Pingback: Are you experiencing science overload? | Watershed Moments: Thoughts from the Hydrosphere

Nat

Well, as reviewers, I think we have some power.

The paper is too long ? ask the authors to shorten it.

The paper is not interesting ? adds very little to previous publications ? reject it.

In addition to reviews, I read maybe two papers a years thoroughly. But I often come back to papers that I went through quickly, when the time comes and I need more details. Often, I’m disappointed that there are not enought details on the methods, so that the result can be reproduced.

Finally, if you think there are too many papers, maybe you should work in a smaller domain, with less researcher involved worldwide, like the geodynamo 🙂

Nick Arndt

Nat

all reasonable ideas, but rather beside the main point, which, for me, is the fact that thousands if not millions of papers are being written and very few are being (thoroughly) read. Stephen’s comments tend to confirm this. I wonder if all papers on the dynamo are thoroughly read; and if this is the case, do workers in this field only read about the dynamo?

I think Stephen’s point about whether a policy could be applied across disciplines is interesting. Of course we are not able to impose rules — but other disciplines do not have quite the problem we have in the earth sciences where we need to provide a lot of detailed description or analytical/experimental detail. Papers in physics (or on the dynamo?) are shorter and are most probably read more or less completely.

Would it be possible to put the detail and background information into data banks and just publish the ‘key points’ and graphical abstracts, which would be read? But even this does not avoid the problem raised by the manner in which scientist are judged by the metrics – the number of papers, the number of citations and the impact factor of target journals; and the terrifying multiplication in the total number of journals that now exist!

Stephen Tooth

It’s good to see someone prepared to say this. I always tell junior colleagues with research/teaching/admin roles to try and write one or two good quality first-authored papers per year, and if that can be supplemented by one or two additional good-quality papers with second, third or lower authorship, then that should be sufficient. Unfortunately, that viewpoint rarely coincides with the level of output expected by promotions committees and the like, which tend to look at quantity not quality of output. Undoubtedly, the present rate of academic publishing is not sustainable and is wasted effort if large masses of the outputs are not widely read. There is a real tension between trying to do interdisciplinary work (and therefore reading more and more widely) yet actually only having time to read a fraction of papers on topics that become more and more specialised. I’m not sure what the solution is ….

Nicholas Arndt

Hi Stephen, thanks for your comment, particularly about the special problem of interdisciplinary research. My impression is that a decade ago it was very difficult to get published papers that spanned several disciplines, but now, with the explosion of journals on every imaginable topic (and of every imaginable status), this is no longer so difficult. The question is whether all these papers are ever read.

I’m told that in other fields, physics particularly, there is less of a problem. Open-access publications are more common, and many more papers are published. And they are read because on average they are far shorter than those in the earth sciences. Maybe the solution is to allow the publication of no more than one long and solid/stolid geoscience-style paper and limit all others to 1-2 pages.

Stephen Tooth

I think you capture the current situation well in your first paragraph. I also agree with the first 3 sentences of your second paragraph. The 4th sentence contains an interesting idea, but practically could never be implemented. Even if such a policy could be agreed across a discipline or disciplines and across institution or institutions – which is highly unlikely – how would it be policed? But the underlying point about trying to get an appropriate balance between a few solid/stolid papers and more numerous shorter/punchier papers that may be more widely read would be a nice one to promote. I pride myself on reading pretty widely, but even I rarely a full paper nowadays (unless reviewing of course) … title, abstract, intro, and conclusions yes, but the bits in between? Not usually in detail ….

And judging by the trend for ‘key points’ and graphical abstracts that now often have to accompany the standard abstracts, I suspect that many people are reading even less than this.

Cindy Prescott

You have hit the name squarely on the head, Dr. Arndt. Science is now caught up in the perilous growth-at-all-costs paradigm. It’s time for the consequences to be given serious consideration.

Nicholas Arndt

Indeed! I would be interested to hear what consequences you have in mind.

Januka Attanayake

Careers in academia appears to be increasingly dependent on the quantity and not on quality. Good science can be done only in a relaxed environment. This is why historically best science has been done by those considered affluent. They were not bound by quantity. Ideas cannot be manufactured, they just happen, and the chance for that is greater in a relaxed environment.

Nicholas Arndt

Hi Januka, what you say is very true. I think that most of us would be happier if we could have the time to think carefully about what is to go in a publication, and this is a privilege only available to people with a steady source of funds. The problem now is that, in order to get these funds, many papers must be published … And then, once published, these papers are not read because all potential readers are busy writing.